When watching Simon Godwin’s production of King Lear at the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s Klein Theatre in DC’s Penn Quarter, you might imagine this is a little what it felt like to see the original production proceeding under the Bard’s own eyes. Not in the sense of a strict traditionalism — the play feels deeply inflected with contemporary pop culture. But the crowd is ready to laugh, the actors seem to feed off its energy, and the clear-eyed cuts and direction by Godwin make the narrative and characterizations so clear that the centuries of cultural distance fall away. Without bothering with any high-concept modernized setting, the play makes a point of speaking directly with its audience.

There’s a cost to that approach. King Lear is one of the most haunting tragedies in literature. Interpreting it for an audience that’s enamored with re-binging Succession makes it difficult to convey the depth of emotion and mystery that a more measured pace and subtler direction would support. But by highlighting comedy, virtuosic performance, and storytelling, this production has accomplished something distinctive: making one of Shakespeare’s least accessible greats deeply enthralling.

At the core of the production’s appeal is a collection of performances that make characters’ actions feel intuitive while still skewing larger-than-life. Patrick Page takes an invigorating approach to the title role. In the opening scene, his Lear strides on stage in a fur-lined coat and shades, and establishes himself as impetuous, cocksure, and commanding, seeming to be taking an early retirement to enjoy the end of his prime years. The energetic performance drives the play along. Page has a subtle enough understanding of the character that false notes are rare. Performances of Lear are defined at the outset, and here, when Lear asks his daughters to prove their love for him, it feels like a game with a foregone conclusion that Cordelia throws a wrench in by offending him, causing Lear to lose control. It’s this movement between light-hearted irony and uncontrollable ego that defines Page’s performance.

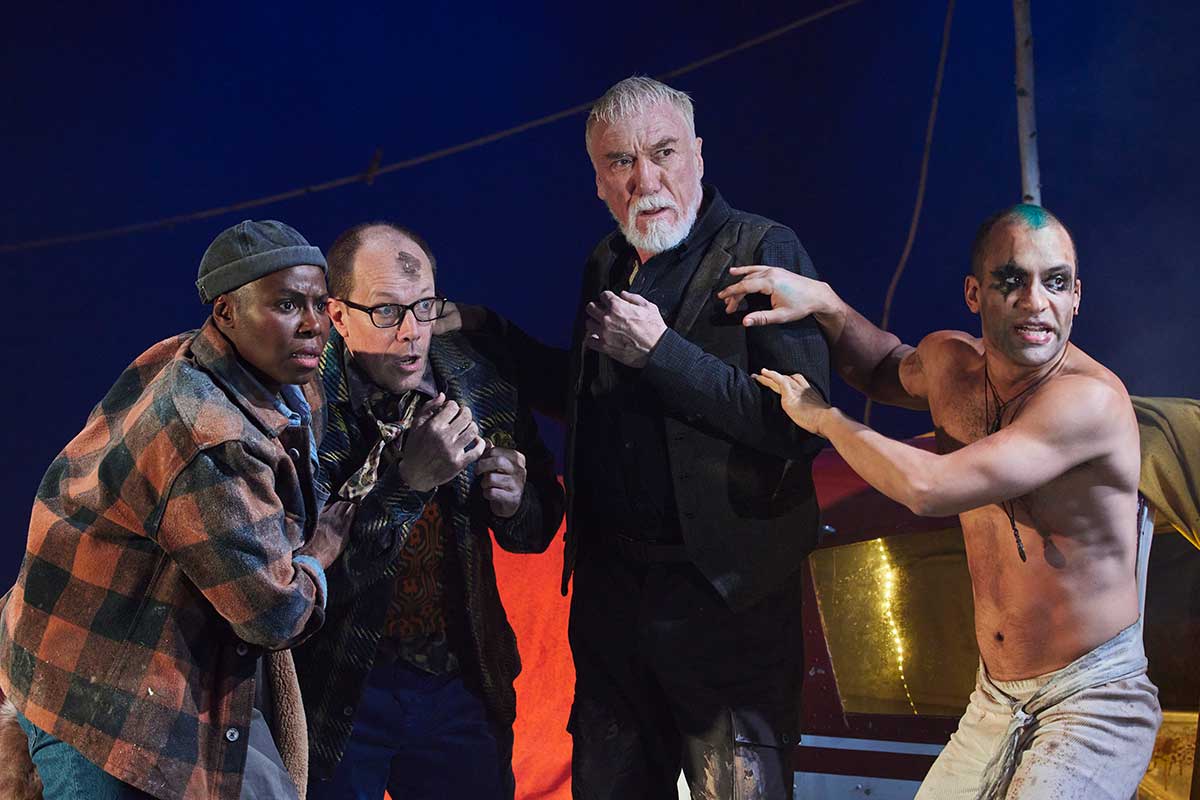

The savviness of the direction becomes clearer with the supporting characters, who often lean into tropes. Goneril and Regan are costumed somewhere between Cinderella’s stepsisters and reality-show stars. Edmund opens his famous “stand up for bastards” scene by shadowboxing, and concludes it drinking whiskey, giving off vibes of an ‘80s corporate climber. Bookish, bespectacled Edgar enters wearing pants that might prompt audience members to joke, “Where’s the flood?”

The stock characterizations avoid being reductive by allowing human complexity to shine through. Gloucester, played by veteran Shakespearean Craig Wallace, is presented so affably that he gets audiences to laugh from the outset despite his questionable treatment of Edmund, and react in real shock when he’s blinded. His character development, an afterthought in other productions, is carefully directed — he only fully turns against his son Edgar when Edmund appears to be hurt, which makes their later reunion more moving.

That careful handling of narrative, in part because of Godwin’s smart cuts, might be the production’s biggest accomplishment. Lear’s journey takes on a clear arc, making obvious his role in his own downfall. His sudden shift from reckless, why-can’t-you-relax joviality to violent rage when staying with Goneril, and her hurt at his actions, point to an ambiguity in who the victim is. When Lear comes to Regan, her exaggerated sadism (she later gives the blinding of Gloucester a grotesque sexual charge) demonstrates that Lear made a mistake in not sticking with Goneril — and that it was not just in his initial act of rage, but in repeatedly looking for space for his ego and unchecked impulses. Finally, when he’s reunited with Cordelia, his misery shows that only now is he humbled enough to deserve her love. His evolution seems to be a positive interpretation that will sit well with the expectations of a TV-trained audience.

In this production, Lear seems to fear madness, but isn’t ever in full danger of it. He stays on a spectrum between unfettered irony and deep rage and grief. But that makes key scenes, like his speech on the heath, lack some drama. He doesn’t reach the depths that a more self-doubting Lear can. His conversations with the Fool, rather than reaching the level of existential riddles, are straightforwardly comic. And the play’s focus on keeping the audience riveted doesn’t always provide space to digest the kinds of questions that should result from those conversations.

This becomes a bigger issue after intermission, when the play careens hard into the tragic. Because the action doesn’t resolve with Lear and Cordelia reuniting. After that moment, some energy is lost, and deaths of major characters lack their full impact without a full exploration of the play’s themes. (Shakespeare’s rapid final-act body counts are never easy to handle.) Even here, the play makes up for it by finding opportunities to crowd-please; Edgar enters his fight with Edmund with the flair of a WWE wrestler.

The ending may come quickly and a little too breezily, but the director and his cast have charmingly persuaded Lear to open up and talk to its audience. In doing so, they’ve made it reveal something new about itself — an accomplishment that many, more self-serious Lears, isolating themselves in rage on the heath, can only hope to do.

Feature image by DJ Corey Photography

For more stories like this, subscribe to Northern Virginia Magazine’s Things to Do newsletter.