Long before Northern Virginia became a destination for top aerospace companies, an experiment on the Potomac River made the world stop laughing at the idea that man could fly.

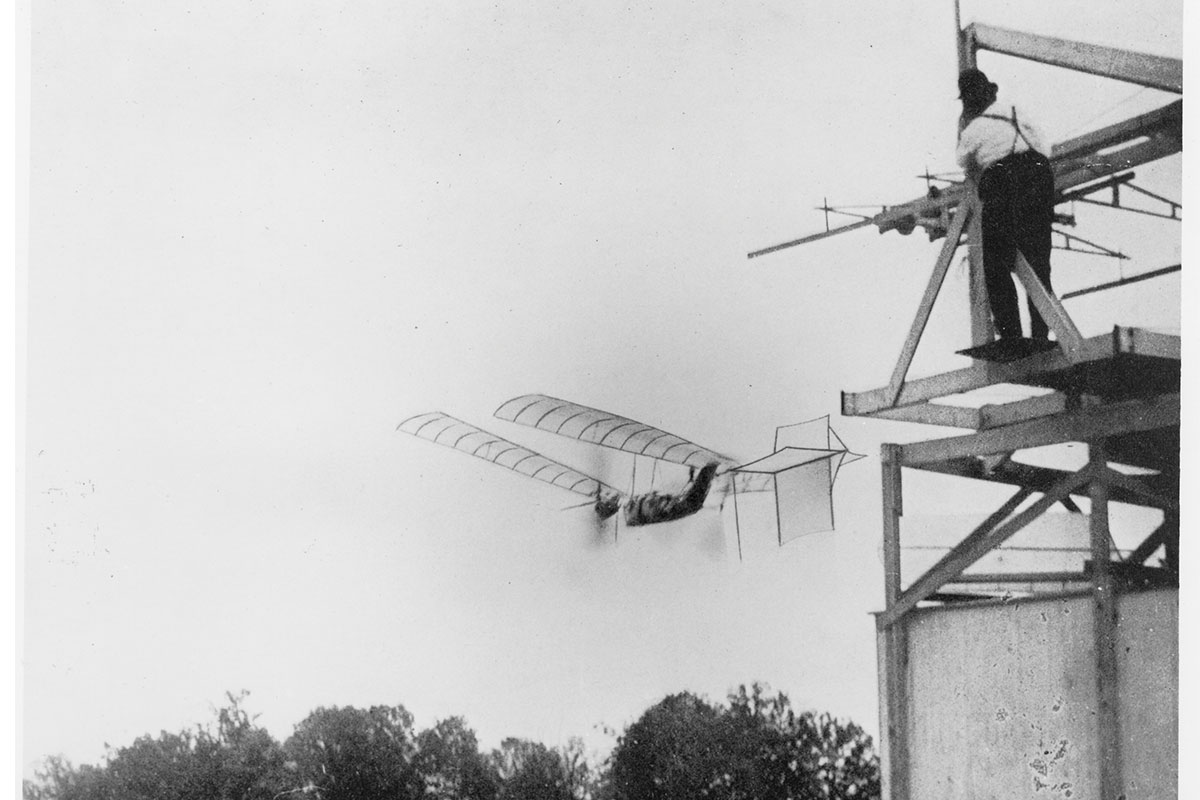

On May 6, 1896 — five years after the Boston Daily Globe called him “the most laughed-at man of the day” for his optimism regarding mechanical flight — Samuel Pierpont Langley achieved the first successful flight of an uncrewed, engine-driven, heavier-than-air craft, launched from a houseboat anchored off a small island near what is now Marine Corps Base Quantico.

“I witnessed a very remarkable experiment with Professor Langley’s aerodrome on the Potomac [River],” wrote Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone, who was a friend of Langley and accompanied him for the test flights. “No one could have witnessed these experiments without being convinced that the practicability of mechanical flight had been demonstrated.”

While Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, has forged a spot in the American imagination as the site of the Wright brothers’ 1903 achievement of the first crewed flight, the birthplace of Langley’s success seven years earlier has fallen into periodic obscurity and disrepair. But the island, known as Chopawamsic, always had plenty of promise.

The 13-acre island has made headlines lately, as it’s for sale for $4.7 million. Meanwhile, nonprofit group the Langley Flight Foundation is trying to bring more attention to Langley’s accomplishments. While the group is hoping to preserve the island as a national heritage area, the asking price is steep.

So Chopawamsic’s future remains uncertain, “awaiting a new owner with imagination and purpose,” as its real estate listing states.

“At this time, we don’t have the funding needed to acquire and responsibly maintain it,” says Chris Hornung, president of the foundation. “We hope that the more attention the foundation can bring to the significance of the events that occurred there, the greater chance funding can be identified.”

Over the years since Langley’s flight, the island served as a hunting club, a private home, and a party venue — but it hasn’t had a permanent resident since 1979.

Era of Abandonment

Chopawamsic Island is named for the creek that divides Prince William and Stafford counties and feeds into the Potomac just south of the island, a mere 300 yards offshore from the Marine Corps airfield that is home base for presidential helicopter Marine One. It lies in Stafford County, although the closest landing at Quantico is in Prince William.

Jo Knight, a longtime Stafford County real estate agent who briefly owned the island around 1990, says the island was once a peninsula jutting out from the Stafford side of Chopawamsic Creek, but erosion severed that tie over time.

The island was further isolated in the 1930s, when the Marine Corps reclaimed marshland and moved the creek farther south to expand the airfield at Quantico.

Chopawamsic last made headlines in 2018, when current owners Steve, Ray, and Abe Sami of Falls Church listed it for sale for $15 million. The Samis had purchased the island from Knight and her business partner in 1991 for $375,000. In 2022, the asking price came down to the current $4.7 million.

“In the beginning, for us it was, ‘Let’s get a price that will get attention,’” says listing agent Nick

Letendre of Samson Properties. He said the current price of $361,000 per acre better represents the going rate for waterfront property in the region today, although many other properties don’t come with the same challenges as Chopawamsic.

The island’s isolation has made policing trespassers a challenge at times. Letendre says the owners have installed surveillance, but that hasn’t stopped the occasional intrepid YouTuber from broadcasting from the remote site. A video posted within the past two years on the YouTube account Edwin’s Travel Log shows the extreme state of disrepair of the buildings, with an entire side of a house collapsed over an eroding hillside, leaving a brick fireplace and chimney standing exposed and isolated.

Letendre — who says the island’s owners declined to be interviewed for this article — acknowledges that the three structures on Chopawamsic are likely beyond repair.

Chopawamsic’s last permanent resident, Navy physician Dr. Wesley Fry, bought the property in 1958 for $14,000 as a quiet place to live while working as a surgeon at Quantico Naval Hospital. Fry restored three houses on the island (four others were teardowns), planted fruit trees, and dug a well and a swimming pool by hand because large equipment couldn’t reach the property.

According to a 1979 Washington Post report, both John Lennon and a Saudi prince were once interested in buying Chopawamsic. After Fry finally sold it to Columbia Tours International in 1983, the island was largely abandoned. When Knight and her business partner bought it in 1989, she remembers getting quite a surprise while exploring one day.

Finding the door ajar, she entered one of the three buildings to find an abandoned but richly furnished home, with full china closets and a piano. When she went upstairs, “I saw this big, beautiful, old antique bed, and right there on the bed was a billy goat with a long beard. It was standing on the bed looking right square in my face.”

Knight named the goat Chop, after his island home. She grew fond of the animal and appreciated how he kept the grass clipped on the paths.

“It took care of him, and he took care of it,” she says.

But keeping vandals off the island became difficult. While the shoreline that faces Quantico is in restricted waters — boats that have not been given clearance from Quantico’s commanding officer are not permitted — the Marines have no authority over the waters on the eastern side.

One day, Knight says, she received a call from the watchtower at Quantico, reporting what looked like vandalism on the island and offering to check things out.

“They called me back and said that somebody had stabbed the goat to death,” Knight says, adding that she never found out who was responsible for killing her animal friend.

Hunting for a Purpose

Chopawamsic — or Chappawamsic, as Stafford County historian Jerrilynn MacGregor notes was the spelling until commercial map publishers changed it in the early 19th century — was known historically as Scott’s Island, after the Rev. Alexander Scott, who acquired it in 1724. The island was part of a vast landholding that Scott amassed over his lifetime.

MacGregor notes that about two-thirds of Stafford County’s historic property records were destroyed during the Civil War, making it difficult to trace the exact provenance of the island until about 1863, but despite many claims to the contrary, she says it’s hard to imagine the land being used as a primary residence during this period.

“From the perspective of a landowner of the 17th, 18th, and even 19th centuries, there wasn’t much you could do with an island,” MacGregor says.

“Other islands were pretty much useless,” she adds. “Even if the island included some arable land, you had to lug the tools, seeds, and workers out there to plow, plant, and harvest the crop there. After harvesting, the crop had to be loaded into boats and brought back to the mainland. That was entirely too much work when there was plenty of usable land that was more accessible.”

By the late 1800s, she notes, it became fashionable for wealthy men to set up hunting clubs along the Potomac River and Aquia Creek. In 1887, Chopawamsic Island was bought by a group of hunters known as the Mount Vernon Ducking Association, with plans for the construction of a clubhouse. Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th U.S. president, is reported to have been a club member, as was Langley.

Before he began his experiments with the series of aircraft he called “aerodrome,” Langley was already a renowned astronomer and physicist and served as secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. After his successful uncrewed flights in 1896, Langley received a $50,000 federal grant, plus additional money from the Smithsonian, to adapt his uncrewed craft to carry a pilot.

When he returned to Chopawamsic to test the new craft on October 7 and December 8, 1903, he failed on both attempts. Nine days after the second failure, the Wright brothers completed their successful flight in North Carolina.

The failed aerodrome flights were not only an embarrassment to Langley and the Smithsonian, but they were also a source of drama within the hunting club, as Langley staged his crew there for months during their preparations and forbade any outsiders, including club members, from accessing the site.

An August 1903 article in The San Francisco Call newspaper reported that another hunt club member by the name of Truxtun Beale, who had served as a diplomat, threatened to ambush the island with a herd of newspaper reporters eager to follow the flight story. “He will demand the withdrawal of the airship intruders,” the story states, “and if they are impudent, he will proceed to clear them out at the points of pistols,” before sending for his new bride to join him at the clubhouse.

What’s Next?

More than a century later, Letendre says he’s had interest from a few “dreamers” with visions of using the island as a wedding venue or a home for a nonprofit. He says he has always thought Quantico would be a logical owner of the land, and he’s even brought his own creative talents to bear in pursuit of that outcome.

A musician, Letendre was frontman and lead guitarist for In Remembrance, an alt-rock band formed in 2008 to honor members of the armed forces, and specifically his own brother, Marine Capt. Brian S. Letendre, who lost his life in Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2006.

A few years ago, Letendre says he and a former bandmate volunteered to sing the national anthem at the Marine Corps Historic Half Marathon’s pre-race expo in Fredericksburg so that they could get in front of the individual in charge of acquisitions for the base. But the meeting ended quickly.

“He changed the subject faster than we could think,” Letendre says.

Asked if Quantico has considered purchasing the island, the base communications team stated only that “Marine Corps Base Quantico will always evaluate additional ways to further ensure the safety and security of the base and its people.”

In 2020, a group of Stafford County residents formed the Langley Flight Foundation to commemorate Langley and his flights.

Hornung, its president, says that in addition to bringing more attention to Stafford County’s role in aviation history, the foundation hopes “to leverage the interpretation of this historical achievement to create a compelling tourism attraction [at the Stafford Regional Airport in Fredericksburg], implement STEAM education initiatives to encourage the pursuit of aviation- and engineering-related careers, and to attract high-quality employment opportunities to the region.”

The group’s first major project is the construction of an exact replica of Langley’s Aerodrome No. 5 — the model that succeeded in its uncrewed flight from Chopawamsic — for display at the county’s airport or in a history museum that is in the works. Hornung says funds have been raised for the replica, which is scheduled for completion on May 6, 2024, exactly 128 years after the original flight. The original Aerodrome No. 5 is on display in the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.

While the foundation maintains its efforts, Letendre is still looking for a suitable buyer. His listing says the property offers safety in the form of “security patrols provided by the U.S. Marines and the Coast Guard” — plus a “traffic-free commute.”

“Rebrand it with your name, and cement your legacy in history, for generations to come,” invites the listing. That is, if you have $4.7 million lying around.

Feature photo courtesy Nick Letendre

This story originally ran in our April issue. For more stories like this, subscribe to Northern Virginia Magazine.