On the evening of Oct. 14, 2002, Linda Franklin was loading supplies for her new Arlington townhouse into her car at The Home Depot in Seven Corners. It was a typical Monday, and a typical after-work errand, mundane even. Except for the fact that Franklin’s post-workday stop was during the height of the DC Sniper madness, when victims were being claimed by the elusive duo at a fast and furious pace.

Franklin, a 47-year-old FBI analyst, was the 13th victim to be murdered while simply going about the business of life.

By then, local law enforcement and the media knew the drill.

At the same time Franklin was shopping at The Home Depot, Alexandria Sheriff Dana Lawhorne, then a police detective, was at home with his family in Del Ray, watching—what would quickly become ironic—a police drama called Third Watch. He recalls he was telling his family that working in law enforcement was nothing like the dramatic portrayal on television. But then the station cut away to breaking news—yet another shooting, this one in Northern Virginia.

“So I got up, and [my family] said, ‘Where are you going?’ I said, ‘I’m going to go get my badge and gun and get in the car. Can’t find nobody sitting here,’” recounts Lawhorne.

This post originally appeared in our November 2019 issue. Stay up to date on all the latest news in NoVA by subscribing to our e-newsletters.

Lawhorne was not alone. Within moments of the news alert of the shooting at The Home Depot, hundreds of federal, state and local law-enforcement officials from across the region were in their cars driving somewhere. Eager to do something, although nobody was quite sure what. The crime scene at Seven Corners became overloaded with detectives and captains and sheriff deputies—essentially an all-hands-on-deck approach where all the hands in the region showed up in one place at one time.

By the time Tom Manger, who was chief of the Fairfax County Police Department at the time, was ready to give a press conference that night, about 20 members of the media were also there to cover it.

“It was just such a chaotic situation to keep [law enforcement and media] out of the crime scene so they didn’t contaminate the crime scene,” says Manger, who is now the senior associate director for the Major Cities Chiefs Association. “Everybody wanted to be briefed on what was happening.”

For a full timeline of the DC Sniper case, click here.

And so went the seemingly never-ending cycle. A shooting, a chaotic response and—for three weeks in October—a region at the mercy of a murderous duo intent on randomly shooting as many people as they could. When it was all over, the duo had murdered 17 people and wounded 10, in the DC region and across the country.

“Heinous and cold-blooded killings”

When the duo was finally apprehended on Oct. 24, 2002, the complicated case of John Allen Muhammad and Lee Boyd Malvo slowly came to light—as the younger Malvo submitted to hours of interviews with law enforcement, psychologists and social workers—painting a picture of how a 17-year-old from Jamaica came to partner with a twice-divorced father of three to go on a killing spree in the United States. Much ink has been spilled on the relationship—which, according to multiple media reports and court records, was essentially one of Muhammad stepping in as a father figure for Malvo, and ultimately devolved into a controlling relationship that saw Muhammad training Malvo to carry out the killing spree—and that relationship now stands at the center of a Supreme Court case.

Muhammad was convicted of capital murder on three counts and was executed by lethal injection 10 years ago, on Nov. 10, 2009, in Jarratt, Virginia. But, 13 years after Malvo, now 34, was sentenced to life in prison (on Nov. 8, 2006) for the murder of Linda Franklin, his case is once again in the headlines.

In October, the United States Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Mathena v. Malvo, which addresses the question: When juveniles are sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole, should their youth be taken into account? (Randall Mathena is the warden at the supermax Red Onion State Prison in southwest Virginia where Malvo is behind bars, a stand-in for the state of Virginia on legal documents.)

For the justices on the Supreme Court, the question of whether or not Malvo should be executed is not on the docket. Neither is whether he should get life in prison without parole. The court is exploring the very limited question of whether a juvenile’s age should be taken into consideration during sentencing in Virginia.

If the justices rule in favor of Malvo, his case—and his life sentence—could get another look.

The outcome of the Supreme Court case should be open and shut, according to Virginia’s Attorney General Mark Herring. He’s taken the position that two recent court cases calling for youth to be a factor in sentencing don’t apply to Virginia’s laws: Miller v. Alabama, the 2012 case where the Supreme Court ruled mandatory life without parole is unconstitutional for juvenile offenders; and Montgomery v. Louisiana, the 2016 case ruled Alabama should be applied retroactively. Herring argues neither of those cases apply to Malvo.

Via a written statement, Herring told Northern Virginia Magazine: “Malvo remains a convicted mass murderer who terrorized an entire region with his heinous and cold-blooded killings. I will keep working to ensure that he faces justice and serves the sentences that were imposed.”

The case does come with some political implications for Herring, a Democrat, who was once thought to have political aspirations to run for governor. That talk has been muted by a headline-grabbing blackface scandal. But this Supreme Court case puts him in the national spotlight as a tough-on-crime Democrat—someone who is out of step with the burgeoning criminal justice movement that recently unseated elected prosecutors in Fairfax and Arlington who were seen as too conservative.

“It is a popular opinion to want to keep the DC Sniper behind bars,” says former George Mason University law professor Richard Kelsey. “So he gets a political twofer here: He does his job as a lawyer, and he also gets to make an affirmative statement about a person that nobody really wants to feel badly for.”

“A system that would be a little more fair”

But even with a crime spree that gripped the region—and the country—like the DC Snipers, there are some surprising voices willing to give Malvo’s sentence another look.

“One of the definitions of forgiveness is that you get rid of the anger and resentment [toward the person] who’s done something to you because if you don’t, then you’re miserable,” says sniper shooting victim Paul LaRuffa. “People don’t take that into consideration. They think you should feel the same way, have the same anger.”

LaRuffa narrowly escaped death in September 2002, weeks before the DC Sniper shootings became a macabre preoccupation. Although the incident has become known in the popular imagination as “Three Weeks in October” (the name of a book about the case by author Charles Fleming and then Montgomery County Police Chief Charles Moose), in reality the rampage went on for much longer.

The first victim was in February 2002 out on the West Coast where Muhammad and Malvo lived together. That was followed by a March shooting in Arizona and then an August shooting in Arizona. LaRuffa was the first victim in the Washington region, shot five times while in his car after closing his restaurant, Margellina, in Clinton, Maryland.

“Needless to say, it was a tremendously shocking experience,” says LaRuffa, who survived and continued on as owner of his restaurant for six more years before selling the business in 2008. “It’s confusing. It’s shocking. There’s hardly words to explain.”

The night he was shot, the doctors had him in surgery for seven hours to save his life. He was on a breathing machine for about three days, and he ended up being initially released after 10 days in the hospital. Now, LaRuffa and other surviving victims are about to relive their trauma all over again as the Supreme Court takes up the case of Malvo.

“I think there’s good reasons why youth should be considered,” says LaRuffa, who says he believes young people can be rehabilitated instead of banished from society with no hope of ever returning. “There’s doomed to life in prison and there is no hope, and I guess I’m in favor of a system that would be a little more fair.”

“He was brainwashed”

Seventeen years later, LuRuffa and others are revisiting the case with a somewhat cooler head, but, by the time the gunmen were caught back in 2002, many of those formerly terrorized hostages were out for blood. Calls for both men to be executed were widespread, and both trials were moved out of the DC region on the premise that no one in the Washington metropolitan area could possibly be an impartial juror. Eventually Muhammed was found guilty and sentenced to death—a series of events that was in some ways influenced by 9/11, which had happened the previous year.

“He was executed under a law that I passed,” says former Republican Rep. Dave Albo, who represented Fort Belvoir in Virginia’s House of Delegates at the time. “We added the category killing during an act of terrorism.”

After 9/11, lawmakers in the General Assembly were eager to do something—anything. And so they passed the Anti-Terrorism Bill, a broad overhaul that modified everything from executing search warrants to tapping computerized phone lines. One of the provisions revolved around the death penalty, creating a new avenue for executing criminal masterminds who were responsible for murders but didn’t actually carry them out—Osama bin Laden, for example. Lawmakers were concerned that the death penalty wouldn’t be available in Virginia for bin Laden, so they created a new category for execution.

“So, that was one of the charges that Muhammad was convicted on,” explains Albo. “Now the one reason why I thought that Lee Boyd Malvo should not get the death penalty—just my personal opinion—was not because he was a juvenile, but because I got the impression he was brainwashed by this guy he perceived as his father.”

“We didn’t know what we were looking for”

“Non-traditional hostage taking.” That’s the phrase that eventually emerged in law-enforcement circles to describe the DC Sniper case in 2002. It had all of the elements of a traditional hostage taking, except for a static stronghold or crisis site. Instead of a handful of hostages, the theory goes, the entire region was taken hostage. Federal law-enforcement officials were the first to recognize the situation as a non-traditional hostage taking, persuading local police to adopt that posture.

“It changes the way you use the media,” former Alexandria sergeant Derek Gaunt explains. “The media was the telephone. They were communicating through the media, and they were receiving messages back from law enforcement through the media. At the end of the day, you’ve got dialogue with a guy who’s got 8 to 10 million people hostage.”

Now, almost 20 years later, some police officials are second guessing the investigation. One of the first lookouts was for a blue Caprice, the car the snipers were actually driving around in. But that lookout was ignored in favor of the infamous one for the white van, a red herring that may have prolonged the killing spree and contributed to the body count.

Alexandria Sheriff Dana Lawhorne recalls the night of The Home Depot shooting, and immediately jumping in to help with traffic stops. “I listened to the radio traffic, and I hear that they were starting to stop white box trucks on Duke Street [in Alexandria]. So I just went out there and helped them stop white box trucks,” he says. “Looking back, it’s clear we didn’t even know what we were looking for.”

Complicating matters even further that evening, police ended up chasing what turned out to be a bogus lead from a customer at The Home Depot, telling investigators he had seen the man who shot the woman. In a post-9/11 environment, the witness described the man as Middle Eastern, and he said he was driving a van with a busted tail light. Manger says it took police just under 24 hours to determine what he was saying was a lie, but in the chaos of the moment the bogus lookout sent police scrambling in the wrong direction looking for the wrong thing—potentially letting the real culprits slip through the cracks in the process.

And then there was the infamous moment when the snipers forced Montgomery County Police Chief Charles Moose to say cryptically, “We have caught the sniper like a duck in a noose,” on live TV.

“I felt like a commander in a war zone”

As the crisis dragged on, a sense of weariness set in.

“I felt like a commander in a war zone,” says Charlie Deane, who was chief of the Prince William County Police Department at the time. “The people you’re charged with protecting, the community, are at risk of being randomly killed. And then you’re concerned about your own staff being targeted or killed in a gunfight with these fools.”

For people who lived in Northern Virginia at the time, being taken hostage meant altering daily habits. Things that once seemed mundane and prosaic were transformed into white-knuckled moments of terror. Victims had been mowing lawns, pumping gas, loading trunks. That created an atmosphere where everybody was second guessing every action every moment of every day. Some people shut down and stayed home. Others defied the terror and moved on about their lives anyway.

“I’m a cyclist, and I would still go out for my daily ride. But my wife pleaded with me not to,” says Kerry Donley, who was mayor of Alexandria at the time. “That was the tension that people were under. People were questioning whether they could pump gas or go to a Home Depot.”

“Incredible sudden anguish and loss”

The justified hysteria that surrounded the DC Sniper shootings still looms large in the collective conscious of those who lived in the region during that brief—but at the time, seemingly endless—period.

While residents wait for the opinion of the Supreme Court, it’s stirred up recollections of what is was like to be living in Northern Virginia during that time.

Because there was no apparent rhyme or reason to the killings, anyone could be a target. The story became a grim national fixation on cable TV and brought the terrorized DC region to a standstill.

People were afraid to pump gas. After-school sports were canceled. Parents stopped taking their children to the park. Everyone was glued to their television for the latest gruesome update, a crime spree that went on for months before authorities were able to find Muhammad and Malvo.

The crime spree also remains one of the largest news stories in DC—and one that continues to come up in reporter circles.

“I’ve never had a stretch that sober in my entire life,” says Pat Collins, a reporter at NBC4 who has covered crime in the region for decades. “You couldn’t drink. You had to always be ready.”

Reporters got used to waiting for the next shooting, dropping what they were doing and driving out to a crime scene that could be hours away, and then do live television for an unspecified period of time with little or no information to report. A lot of the day-to-day coverage was scene-setters: footage of people pumping gas on their knees; interviews with people who changed their grocery shopping habits to avoid walking through parking lots; canceled soccer games and childless outdoor playgrounds. And then the traveling roadshow would set up satellite trucks in a different location 20 miles away.

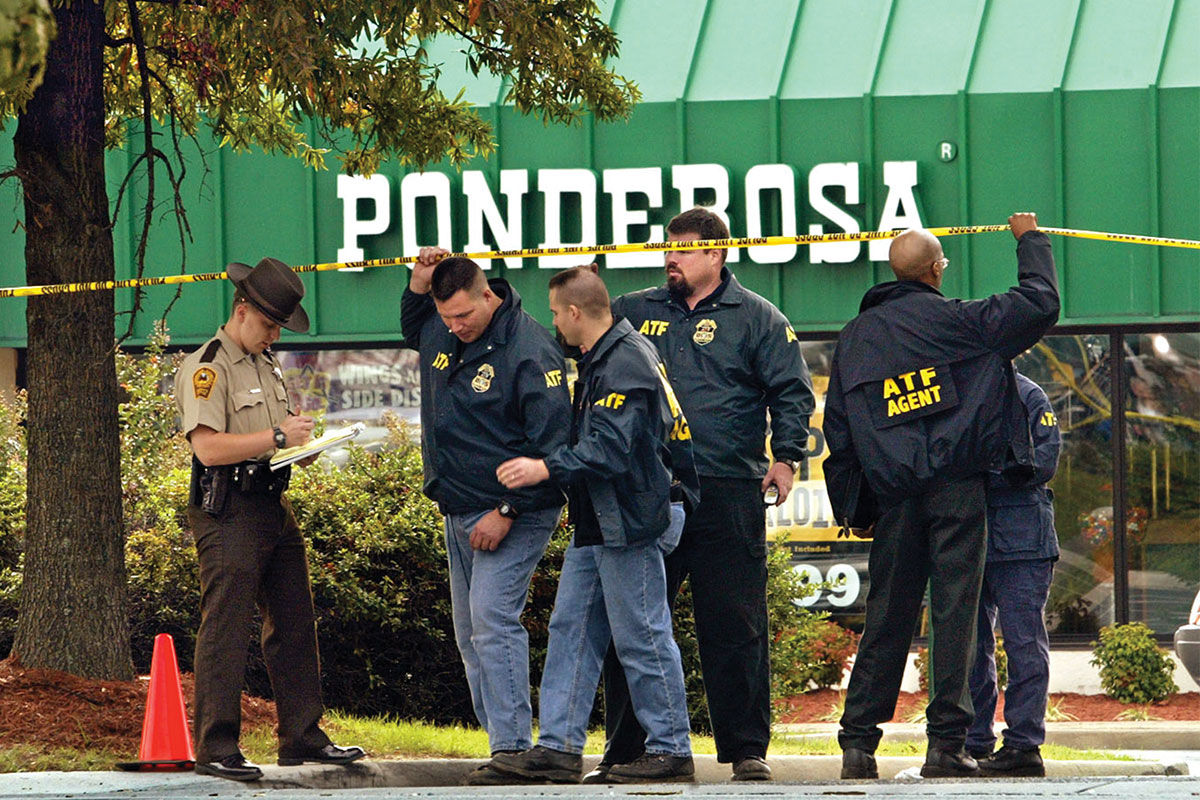

“You were getting fired out of a cannon at night and on weekends,” recalls Julie Carey, another longtime NBC4 reporter. “I remember flying down to Ashland when that one happened at the Ponderosa.”

From the Ponderosa on State Road 54 out in Ashland to Seven Corners in Fairfax County, the snipers had Northern Virginia in their sights. Of the 15 sniper attacks in the Washington area, five were in Northern Virginia.

As the crisis continued, media professionals realized that their reporting was becoming part of the twisted logic behind staging the murders. If the news media reported that all the shootings happened during the day, they would shoot somebody at night. If they reported all the shots happened during a weekday, they would shoot someone on the weekend.

Perhaps most infamously, the media reported that no children had been shot and within a number of hours a 13-year-old middle school student was shot in Bowie, Maryland. And then there were the talking points repeated over and over again on live TV: that the perpetrator was a disgruntled white male with military training driving a white box truck.

“Two-thirds of it was erroneous, and we repeated it like it was the sign of the cross,” says Collins. “Maybe we should have double, double, double checked some of the things the profilers said, some of the lookouts that were given to us, some of the raw information they were using to describe potential suspects.”

The two trials ended up being media spectacles in their own right, extended legal spectacles that invited intense media coverage and endless speculation about the death penalty. Carey says she remembers the sentencing part of the Malvo trial vividly because of the testimony from the widow of the slain FBI analyst.

“I’ve only cried twice in my career, and her husband’s victim-impact testimony was one of the two times,” says Carey. “He brought it to life in his testimony, and I think everybody just felt the incredible sudden anguish and loss of that shooting in that Home Depot.”

“You still have to serve time”

The Supreme Court is expected to deliver its opinion on Mathena v. Malvo by the end of the term in June, perhaps as early as February or March. Even if the justices rule Lee Boyd Malvo should get another sentencing hearing, it’s unlikely that he’ll be released from jail any time soon.

That scary time in Northern Virginia continues to cast a shadow over everyone directly involved—and all those who still remember living through it vividly.

Can a minor who murdered be rehabilitated? The court of public opinion may be split, even the perspectives of victims. For his part, LaRuffa says he’s comfortable in the knowledge that Malvo will never be released, and he’s focused on all the other juveniles who are spending time behind bars for crimes they committed as children.

“There is a difference between an adult and a child, a juvenile—how they think, the development of their brain, their character,” he says. “And that’s not to say that the system means if you are under 18 you get a pass. You still have to take personal responsibility. You still have to absorb the punishment. You still have to serve time.”