For one thing, the name of the company was a joke.

When the founders got serious about their business partnership in 1976, they named the new firm Great American Restaurants. “Nobody else had the name, and I thought it would be funny,” says Randy Norton.

GAR, as the company is referred to these days, had exactly two establishments, Picco’s, a small pizza joint in Fairfax City, and a whimsically named, family themed eatery in Annandale called Fantastic Fritzbe’s Flying Food Factory. So the small company with the big name was funny, in a subtle, subversive way.

Now, 43 rather rapid years later, GAR is a major player in the regional restaurant landscape, with a growing portfolio of 16 robust establishments scattered throughout the suburbs, with the three newest opening in Tysons this spring. You live near one, or maybe two or three: Sweetwater Tavern, Carlyle, Coastal Flats, Artie’s, Mike’s American, Ozzie’s Good Eats, Jackson’s Mighty Fine Food and Lucky Lounge, Silverado and Best Buns Bread Company.

A second Best Buns bakery and Patsy’s American opened in May; Randy’s Prime Seafood and Steaks—an all new concept—is set to open in July. All three are side-by-side on Leesburg Pike. For those counting, that makes 16 Great American Restaurants.

“Now people think we’re serious,” Randy laments. “No, we’re not serious.”

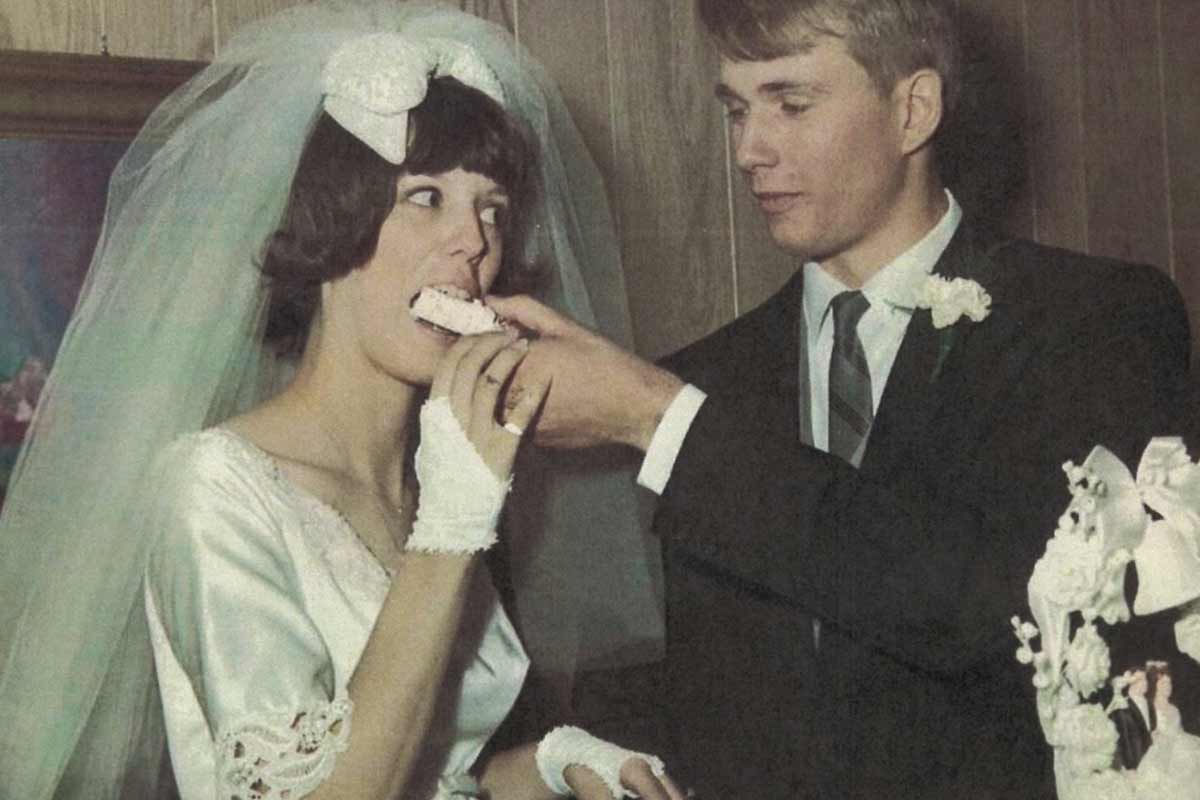

All of this culinary and hospitality success turns on fortuitous episodes of cheating on tests in one Col. McDonald’s geometry class at Fort Hunt High School in Alexandria in 1963. The story of Great American Restaurants is the story of Randy and Patsy Norton, who met over the study of right angles, cubes and spheres (he was the cheater whose grades somehow were always better than hers) and married four years later. It would have been sooner, but her parents slowed things down.

Did Randy and Patsy ever in their wildest imaginations … the question doesn’t even get finished before Randy, the founder and chairman, delivers a decisive, “No!”

“Listen, I was the fifth-generation in the animal byproducts rendering business,” he says during a conversation in a conference room at GAR’s Merrifield corporate headquarters … wait. Scratch that. GAR does not call the nerve center “headquarters,” and this is telling of the nature of the company: “It’s a support center,” Randy says. “We don’t make a dime here …”

“It’s all about supporting our people,” adds Patsy.

Some “20 to 30” employees (Randy’s estimate) keep the machine humming in the support center, across Gallows Road from a Sweetwater Tavern brewery. Randy’s office is upstairs at Sweetwater, but he’s often downstairs in the dining and kitchen areas because of the noise and activity. He likes the hustle and noise. The support center is too quiet for him.

In any case, back to the fifth-generation animal byproducts rendering family: Randy’s family owned Norton and Company Inc. rendering plants in Massachusetts and later Northern Virginia. It’s pointed out there was such a facility at Tysons Corner, off Route 7, until about 30 years ago. “No,” corrects Randy. “That was a slaughterhouse. I would go there and pick up the fat and bones and hides and take it back to our factory in Alexandria” where they were “rendered” into resellable and usable material.

Ah. OK.

“I grew up in a tough business,” he says, shaking his head. “From my perspective, [restaurants] are the easiest business in the world. Everyone else says it’s impossible, but to me …”

“It’s a lot more pleasant,” Patsy finishes, with a laugh. “And before that, they were whalers in Nantucket.”

Eventually, Randy, who trained as an accountant, bought the business from his father and on a whim—a common theme, here—invested “a tiny bit of money” with partner Jim Farley to open Picco’s, a small pizza restaurant in Fairfax City in 1974. But …

“I started to meddle, because that’s who I am,” Randy says, “and we built a bigger restaurant in Annandale.”

That would be the aforementioned Fantastic Fritzbe’s, opened in 1976, and, along with new partner and fellow Fort Hunt grad, Mike Ranney, it was a family affair from the beginning. Patsy made desserts at home and brought them to the restaurant in boxes; she worked the hostess station when called on. Randy manned the popcorn machine—the popcorn was free to all—because they had seen the gimmick work magic in keeping kids happy elsewhere, and by now they had three young children themselves.

The kids were put to work early and often in the restaurants. Soon there was a second Fritzbe’s, this one called Fantastic Fritzbe’s Goodtime Emporium near Fairfax Circle (it’s now Artie’s). And a good thing the kids took to it, because Mom and Dad were admittedly useless in “front of the house” duties.

“I tried to wait tables one time in Annandale and it was a disaster,” Randy says. “I couldn’t remember anything … I’d write the menus [for the restaurant], but I had no clue how to do anything. I could make popcorn.”

Patsy wasn’t much better at the register. “She’d open it and say ‘take what you need’ and we decided she’s not allowed at the register,” says Randy.

“It’s been an adventure,” Patsy says quietly.

Consistently Consistent

For all their joking, whatever the Nortons are doing is working. They feed a lot of people in a lot of places every day, with dependability that does not go unnoticed.

“That consistency over all those years, that’s really hard to pull off,” says Tim Carman, a food reporter at The Washington Post who reviews “affordable and under-the-radar” restaurants, the Nortons’ sweet spot.

The Nortons, he says, “stay focused on the ‘soft middle’ of the dining market that sometimes gets overlooked. You can go [to a Norton restaurant] and get a decent meal that’s affordable and doesn’t have a lot of fancy or expensive ingredients, but the food is often second: They treat you with respect and treat you like a regular.

“They know hospitality, and they know how to take care of not just their customers but their employees, which is key these days with so many restaurants,” says Carman. The company, with its family feel, often gets named to The Post’s annual list of “Top Places to Work.”

Carman says his mother-in-law continually resists his annual offer of a high-end establishment for a birthday dinner. Instead, she insists on going to the Coastal Flats at Tysons. “Nothing makes her happier than to have that lobster roll at Coastal Flats on her birthday,” he says. “And why not? She’s treated with respect, it’s a decent meal and it makes her happy.”

Much of that consistency can be attributed to the intensive training new workers receive from Great American Restaurants. But before that, the fit has to be right.

“Somebody else in the business said, and I believe it every day, ‘You can teach everything about serving a guest but you can’t teach a good attitude,’” says Randy. “When they come through the door for the initial interview, if they don’t have a good attitude, we try to be polite, but we let them know this isn’t the right place for you.”

It’s a good thing then the kids have the right attitude: All three are executives. Jon, 47, is chief executive officer; Jill, 51, is vice president, in charge of construction and design; and Timmy, 44, is research and development chef.

But they didn’t just age into the C-suite, they had to earn it. As children, “they dug gum from out under the tables, they washed between the tiles, they did all the grunt work” at an early age, Patsy says. Gradually, they each entered the ranks of management, but not before having jobs elsewhere.

Jon, for example, was working for a stockbroker in Atlanta and going to school for his MBA when he decided to join the family firm. “I think it’s pretty neat they let us join the company,” he says, adding, “When I called Dad and said I wanted to come home and work in the restaurants, he said, ‘Fine, I’ll fire you, but I’m only going to hire you once.’” Meaning, no one was entitled, and they had to perform. And there would be no second chances if he left the company.

Timmy, who trained at the now closed L’Academie de Cuisine in Maryland, spends his time in the chain’s test kitchen in the rear of Ozzie’s in Fairfax. The best part of his job? “I get to carry on relationships with people who I’ve known for half of my life,” he says. “The restaurant industry typically has a high turnover rate, but here at GAR, we have a fair amount of people who have worked with us for decades in multiple facets of the restaurant.

“The sense of community and hospitality towards our patrons, as well as the staff within, is what makes our restaurants thrive—and a joy to work for,” he says.

The restaurants have different names but they have several things in common, most notably the rooms are intentionally large, with wide aisles, high ceilings and open kitchen lines.

The woman behind the design laughs when asked if she’s had training in design or construction. “Absolutely not,” says Jill. “I was a history major. But I always loved art and design and Dad was doing the construction and taught me how to do it and I took it from there. We work with great architects and contractors—I kind of manage the process.”

For years, Jill says, she and her brothers had been suggesting that the next restaurants be named after their mom and dad, but Patsy and Randy always refused. But when they pointed out that the two new restaurants were going to be side-by-side and connected with common doors, they finally relented. It’s a love story, after all.

Sentimental? Pasty says before they built the Carlyle Grand Café in post-industrial Shirlington in 1986, the location had been a Jellef’s women’s apparel store. “I bought my wedding gown there,” she says. Whenever she was in the building she couldn’t help but remember the corner where the wedding dresses were.

Estimated Value? Priceless, Apparently

As a privately held family company, coming up with a sum total of the value of the 16-restaurant enterprise is challenging, even for the founder.

“How do we know?” Randy asks. “We make enough money to keep going. Another nice thing about being a private company is you don’t have quarterly earnings or have to meet goals or targets.” That would drive him insane, he says.

Only about half of the restaurants “have opened the way we wanted them to,” he offers. “The other half needed an amount of money to get turned around and get going right. Nobody knows when we open a restaurant that does very poorly, we’re just pouring money into it until it gets going.”

“So many others fail because they can’t do that,” Patsy says.

“You have to keep getting in there and grind,” Randy says. They’ve never closed a restaurant (but have sold two over the years).

Both Randy and Pasty are 71 and stay active with golf, travel (“I’ll go anywhere,” Patsy says) and exploring other local eateries. Jon Krinn’s Clarity and Patrick Bazin’s Bazin’s on Church, both in Vienna, not far from their McLean home, are mainstays.

Patsy is involved with several charitable efforts, including, since 2011, Helping Haitian Angels, a Haymarket-based nonprofit that assists an orphanage and school in Haiti. She’s on the board.

She’s also on the board of former Washington NFL team head coach Joe Gibbs’ Youth for Tomorrow, a Bristow-based residential center for teens facing any number of social and cultural dangers. In the past, she’s taught English as a second language and raised guide dogs for the blind.

As for the future, Jon says it will be up to his two children, ages 16 and 13, if they want to be the next generation of Nortons in the family business. As for Timmy’s three kids, 5-year-old twins and a 3-year-old, he says, “I’m planning on it. I hope they will.”

And as for Jill’s 16-year-old Sarah, she’s already working in the bakery on school breaks.

This post originally appeared in our June 2019 issue. For more food content, subscribe to our weekly newsletter.