Many of us turn to chocolate full of expectation: It’s a pick-me-up, an indulgent snack, a sublime pleasure. We use chocolate to celebrate and to soothe. But chocolate isn’t always that simple.

Lately, chocolate bar labels give us a lot more to consider with descriptors like artisan, handcrafted, bean-to-bar, locally produced, two-ingredient and ethically sourced.

An artisan is a worker skilled in a trade, especially one involving making things by hand. Handcrafted is an adjective describing something fashioned by hand. While this sounds pretty straightforward, sometimes things get murky, like when Domino’s created a new pizza with a hand-stretched crust and called it artisan.

Within the chocolate industry these terms can be defined, but they’re not always used consistently. Bean-to-bar is a term used to describe control over the processes, beginning with the sourcing of dried, fermented cacao beans that the maker eventually transforms into chocolate. (Conventional chocolatiers remelt industrial chocolate and then turn it into confections.)

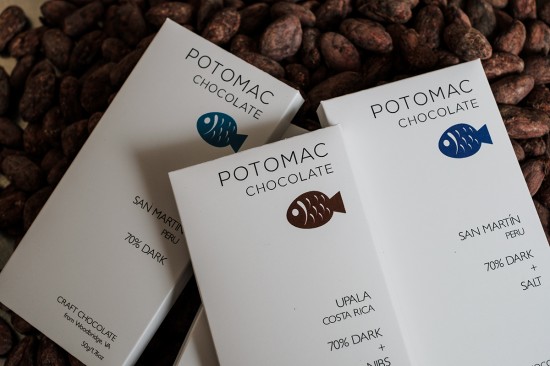

Virginia claims a few bean-to-bar businesses: Potomac Chocolate in Woodbridge, Tightrope Chocolate in Loudoun and others in Charlottesville, Richmond and Lynchburg.

Ben Rasmussen, 41, started Potomac Chocolate in 2010 as a one-man operation out of his house, turning his basement into a chocolate factory and using his custom-built equipment to turn out 250 and 450 bars per batch.

Newer to the local scene are owners of Tightrope Chocolate, Jay Clement and Ben Baboval, who also own Bluemont-based Wild Hare Cider. The two operate what they call their hobby-cum-small-batch business, producing 40-45 bars at a time.

These local chocolate-makers describe their products as monumentally different than other chocolate mass-produced by larger, industrialized manufacturers.

Taste is the first distinction.

Rasmussen didn’t like dark chocolate until he started making it himself. “If all you’ve ever tried is big, industrially produced dark chocolate, a lot of that is really awful. There are a lot of reasons for that, one of which is that there’s only so much fine-flavored cacao, and it’s very expensive.”

Rasmussen says industrial makers work with bulk cacao, which is cheaper and less complex, in order to make a more consistent product. When processing, says Rasmussen, manufacturers “remove a lot of those unique and identifiable flavor notes that I am trying to bring out in order to make a product that they can produce over and over and over again forever. Their chocolate is typically simpler, a lot of times more bitter and less great-tasting.”

Baboval agrees, citing the use of poorer quality cacao, the blending of several varieties of cacao beans and overprocessing techniques used by some larger manufacturers as possible reasons for what they consider inferior chocolate.

The relationships between the science and the art of chocolate-making also distinguish the chocolate produced by larger manufacturers from that of small-batch, artisan makers who wield creative power over their product, expressing themselves as they draw out flavors from the beans through each step of the process (see below).

“This is my interpretation: my choice of origin, my choice of roast profile and refining and conching techniques and profile, my choice of recipe,” says Rasmussen. “There are a million variables in chocolate-making, and every one of them is going to affect the final chocolate, so how I twiddle those bits—that’s what produces my chocolate.”

The ingredients used by larger manufacturers are often different from small-batch makers. Some larger manufacturers use hydrogenated oils, artificial flavors or preservatives and may include soy, dairy or higher levels of saturated fats. Potomac Chocolate uses two ingredients: cacao beans and sugar. While not all small-batch makers use a minimalist approach, limited additives can be important to consumers who may be conscientious about consuming particular ingredients due to allergies, special diets or health concerns.

Dark chocolate that is at least 65 to 70 percent cocoa, minimally processed and consumed in moderation is a better choice nutritionally than other chocolate. Such chocolate contains soluble fiber, minerals, polyphenols and flavonoids, which serve as antioxidants, and has been shown in various studies to positively affect cholesterol and blood pressure and increase insulin sensitivity (USDA), improve cognitive function and assist in protecting skin from UV damage (NIH) and improve performance in trained cyclists (Journal of the Interntional Society of Sports Nutrition, 2015). Many artisan chocolate-makers produce chocolate that is associated with these health benefits.

Part of the reason these small-batch chocolate-makers can control so much of the quality is because of its link to the supply chain. Running a small business allows Rasmussen to develop relationships with his suppliers, which is important to him in an industry associated with unethical and unfair trade practices, including child trafficking, slavery and indentured servitude, as depicted in exposes, government reports and documentaries (see below).

Cocoa farming is a laborious job. The trees on which cacao pods grow are delicate, and care must be taken not to damage them during pod removal. Pods on the same tree don’t necessarily ripen at the same time and must be visually inspected by a harvester to determine maturity.

Rasmussen sources cacao for his Costa Rican bars directly from a farmer with whom he has been working with for four years. For his other bars, he uses importers he has researched and found to be socially, economically and environmentally aligned with his philosophies and goals, and he invites customers to ask questions and explore his processes and sources.

“I would love to get to the point where I can work directly with the farmer for every single bean,” says Rasmussen. “I try to do as direct as possible so that I can have as much control over my supply chain as possible, and I only work with people that I know have direct relationships with the farmers—so I’m only ever one step away—and they’re trusted, reputable people with a history of doing right by the farmers. There’s no point in doing this if you’re screwing over cacao farmers.”

Human rights abuses and unethical trade practices among West African cacao farms surfaced years ago. Despite efforts for change, widespread abuse reportedly continues and, according to some reports, has increased. Even fair trade certification programs (and similar programs like Rainforest Alliance) can’t guarantee chocolate bearing their labels was made without exploitative labor because of the difficulties in monitoring vast numbers of small farms as well as the fact that cacao from certified farms is often mixed with noncertified cacao in order to meet demand. These challenges, among others, are acknowledged by watchdog groups like the Food Empowerment Project and CNN Freedom Project.

John Nanci at Chocolate Alchemy, a cacao importer who sources beans for both Potomac and Tightrope, said in an email: “I’m not just taking the [certifications] at their face value. I trust the people I’m working with. [Fair trade] has a lot of holes. At the end of the day it is [the consumer’s] call.”

Craft chocolate, like beer and coffee, has joined the niche foods market, and it’s a segment encouraging consumers to be educated and informed about the products they buy. “I think consumers these days are much more aware of what is actually craft—of what is actually good—versus what is good marketing,” Rasmussen says. “Consumers are more interested in where their food is coming from … and the story behind the people making it. They’re interested in, and willing to pay for … higher quality products from people they know are making them ethically, that they are putting their own time and effort into it, that they have a creative idea they’re trying to express. And chocolate definitely fits into that.”

A brief outline of making chocolate, with steps by Ben Rasmussen of Potomac Chocolate

• Sort the beans, removing unwanted plant material and separating beans that dried together.

• Roast the beans.

• Crack the beans’ outer shells, or husks.

• Winnow, or separate the beans’ husks (the undesired part) from the inner portion, called nibs (the desired part).

• Grind the nibs until they become a liquid, called chocolate liquor, and add sugar.

• Refine the chocolate until all of the cacao and sugar particles are a smaller size than the tongue can detect.

• Conch, a process involving agitating, aerating, stressing and heating the chocolate to affect its taste, texture and viscosity.

• Age to allow further development of flavors.

• Temper, a process involving heating, cooling and changing the crystals of the chocolate to create its distinctive snap and glossy shine and improve its touch stability and heat resistance.

• Mold into bars.

• Cool.

• Wrap the bars for sale.

Resources

• The Food Empowerment Project’s Chocolate List is a free app detailing sourcing information about chocolate manufacturers: foodispower.org/chocolate-list

• David McKenzie and Brent Swails investigate children working in cocoa fields of West Africa via The CNN Freedom Project: thecnnfreedomproject.blogs.cnn.com/2012/01/19/child-slavery-and-chocolate-all-too-easy-to-find

• The U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of International Labor Affairs (2015)’s Child Labor and Forced Labor Reports on cocoa and coffee farms in the Ivory Coast: dol.gov/agencies/ilab/resources/reports/child-labor/cote-divoire