Embassy Row’s go-to contractor gives a behind-the-scenes on what he’s seen in the area’s prestigious structures of international influence.

By Buzz McClain • Photography By Erick Gibson

A builder must be the master of many trades and a student of dozens of others, some technical, some artistic, and many just a pain in the toolbox.

They need to be on familiar terms with architecture and how to read blueprints; be accustomed to the fine points of structural engineering and the details that accompany understanding how to keep a building from falling down. They need to know when and where to use concrete, masonry, wood or steel, and how to make it look cohesive and intentional; be familiar with mechanical systems, plumbing and heating and cooling equipment, air quality mechanisms, land surveying and odious, labyrinth-like federal, state and local regulations and codes; understand demolition, salvage and reclamation methods, hiring practices, union demands, equipment requirements, local politics and they have to appreciate their role in society’s sustainability and land use issues.

And this is all past as well as present; a builder needs to know the history of how things were done in the past to comprehend why they are being done differently today. And in America, alarmingly, there is no school for builders. There is not one place, or even a system of apprenticeships, where would-be builders can learn the trades and crafts required to have a viable career in construction. Architecture, yes. Engineering, yes. Building, no.

Which is why it’s a good thing for Washington’s embassies that John Bellingham is English.

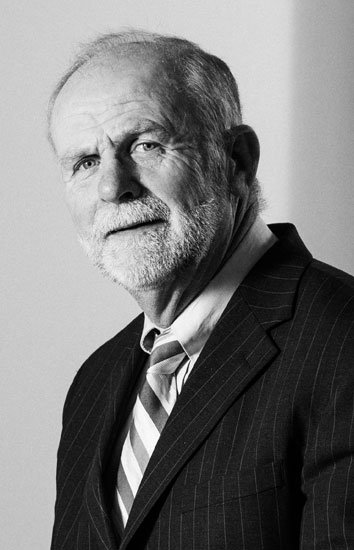

While it may seem ironic that an Englishman is the go-to contractor for the showcase palaces of foreign dignitaries in Washington, D.C., it’s not surprising given that this is exactly what the 63-year-old Bellingham has been groomed to do since he was a boy.

Little did that boy imagine the career the adult has enjoyed. Bellingham is president of the $60-million-a-year, Falls Church-based Monarc Construction, Inc., a seemingly omnipresent corporation with dozens of major projects going up all at once around the area.

The region’s skyline and Massachusetts Avenue’s vaunted Embassy Row owe their cachet to the architects and owners who envisioned their high-rise and palatial glory, but many of those buildings were rendered into reality by a family business represented by a butterfly.

For a builder that’s known for sleek steel and elegant glass accents, Bellingham’s Falls Church headquarters is surprisingly modest, situated in a decidedly unglamorous brick townhouse-like complex at the busy intersection of Lee Highway and the Beltway.

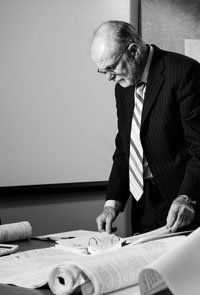

There is evidence of action everywhere, from the bustle of comings and goings in the small foyer that serves as a lobby to the conference room outside Bellingham’s office to the office itself: There are reams of maps, documents, permits and architectural drawings everywhere, labeled and stacked for rapid access, but rendering the conference table useless for actual conferences.

At some point this table in Bellingham’s domain has held a pile of papers pertinent to the Embassy of Ukraine, the Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan, the Embassy of Sweden and the United Arab Emirates Ambassador’s office, and those are just the ones that have won recent industry awards.

Monarc’s client list reads like a role call of the United Nations: the Embassy of New Zealand, the Embassy of Lithuania, the Embassy of Botswana, the Embassy of Australia, the European Ambassador’s residence, the Vietnam Chancery, the Mexican Cultural Institute, the Namibia Ambassador’s residence and the Embassy of Slovenia.

Mention any of these projects and Bellingham has a story. Dapper in a jacket and tie, and with a short graying beard and his glasses on a lanyard around his neck, Bellingham regales the visitor with humorous tales from the margins, but never the expense of a client or employee. A story generally begins with, “One day the [fill in the blank] ambassador called and asked if we could . . .” Such as the time the French ambassador called, “he said he was new in town and found my card in the desk and could I come by and talk to him.”

In the case of the Slovenians, the embassy wasn’t quite theirs when the diplomats made the de rigueur call.

“When Yugoslavia folded the State Department took over the building, arrested all the people who worked there, and took all their guns and arms away—believe it or not, it was an armed fort,” he says. “Then they locked the place up.”

In 1990, the new Republic of Slovenia was given the embassy in Washington and Bellingham took the call—but of course—from the Slovenian ambassador who explained he needed extensive refurbishing of the former Yugoslavian embassy. When he showed up—and Bellingham doesn’t shy from visiting his sites, from conception to completion—he was told they didn’t have the keys yet. So Bellingham provided a verbal estimate in the millions of dollars from what he could see, “but the interesting thing about it was, [during Yugoslavia’s reign] on the roof was this massive antenna. [Yugoslavian president] Tito was a double agent; he was working for the Russians and the Americans as well. The U.S. gave him a huge radio transmission system and while they’d take the antenna off, they left all the transmission gear.”

Bellingham advertised the gear for sale on the Internet “and we got calls from around the world. Finally this Californian with a large wad of cash rolled up and took it all away.” The gear was by then declassified, but Bellingham is familiar with clandestine construction—things that might not show up in the architect’s CAD drawings. The listening devices throughout and the tunnel under the Russian Embassy come to mind.

“We’ve had a couple of incidents where we’ve had certain [domestic] people asking us to do certain things,” Bellingham says with a wry grin. “And obviously you want to help.”

Obviously.

“But the sad thing about it is, a lot of times they won’t support you. If we get caught working for them they deny it. In fact, you sign a paper that basically says you’re on your own.” Chances are negotiating covert modifications and comprehending State Department protocols were not on the syllabus of his schools in England, but he learned fast.

In the 1960s Bellingham benefitted from the U.K.’s dire need to rebuild after World War II; education, particularly at the University of London, was specific to building, with alternating six-month terms of academic study with six-months of hands-on field work, followed by a battery of professional exams and further grooming at other institutions.

When he arrived in the U.S. in 1973, with the intention of working six months and then touring the world before landing back in England, he not only fit in, he found he was light years ahead of American contemporaries. In England he was a registered professional master builder. “There’s no equivalent in this country,” he says, still astonished that there still is not an academic pathway for builders in the U.S.

“America developed after the Industrial Revolution. In Britain, we’ve been banging around the bushes since we were in sheepskin. We developed a structure in the industry where the master builder was someone like [17th-century builder] Sir Christopher Wren, where someone was the designer and the builder; at the Industrial Revolution in America people got away from the building industry, they got into civil engineering. In America you needed people immediately to build canals and roads and bridges and dams and things like that. They trained civil engineers; they never trained builders in this country.”

“You have people who are able to manage projects but have no technical knowledge of how to build the building,” he says of the resumes he receives. “The kids we get in have a very poor understanding [of] how a building is built. Great computer skills and great design skills but how does this all work together? They don’t have the basics.”

The demise of the unions, he points out, “has been a real big influence on the poor quality of construction in America. The unions used to train people. “Today kids come in and expect to run the job straight away and they’ve got no f-ing idea,” he says. Then he laughs at a memory: “I guess it was the same with us.”

While he may have been audacious, he wasn’t ill-prepared: In 1973 he was 23 and explaining how to use tower cranes to his U.S. corporation president.

Bellingham’s climb to where he is now moves like a zig-zagging elevator, rather than going straight up to the top. A position with one firm lead to a position at another firm; one had him working on secret government facilities, another had him rubbing elbows with a senator, and another had him in charge of the physical structures of the British consulates scattered around the country.

The advancements were the result of networking and a big break came when he learned that one of his Washington Rugby Football Club teammates knew someone who knew someone who set up an interview with the president of one of the region’s largest firms; he got the job and two-and-a-half years later moved to a larger firm where he became VP.

Finally he ended up with one of the country’s largest builders, the Texas-based Trammell Crow Company, and since moving to the Lone Star State wasn’t likely (“Move to Texas? You’ve got to be joking,” he says), Bellingham was in charge of the new Washington region branch.

“Originally they wanted to call it ‘Monarch’ with an ‘h’ and a butterfly on it,” he says. “Trammell liked it and said get it registered in Texas, but it was already taken. So we decided to leave the ‘h’ off and keep the butterfly.”

Ah, the butterfly. Yes, he knows the butterfly isn’t quite correct. “We had a project near Georgetown University and we had a big sign up on the site and one day the guy in charge of entomology called up complaining bitterly that our name is ‘Monarc’ but we’ve got a sign with a swallowtail on it. It was confusing his students,” he says chuckling.

Today the company is independent, and besides the work on Embassy Row, Monarc has also helped build or refurbish non-diplomatic edifices such as the Tivoli Theater, the Decatur House Museum, Arlington National Cemetery, St. John’s Church and Parish House, Glen Echo Park, Ronald Regan National Airport . . . the list goes on.

There’s an eight-story homeless shelter going up in D.C.; they’re renovating the Trinity University Notre Dame Chapel; there’s a 12-story condo in White Oak and an exterior renovation of a large co-op building overlooking the National Zoo; a building near the Navy Yard in Southwest Washington; a New York client has them reconfiguring a former property of the International Monetary Fund; a new bus station in the middle of Union Station; work in the apartments section of the old Landsburgh Building, the historic French Renaissance Revival building in Penn Quarter; and “a big condo off Lee Highway in Arlington.”

And the list goes on. As do Bellingham’s stories.

The thing with diplomats, he says, “is they all talk to each other. We did a massive renovation of the European Ambassador’s residence and the next thing you know you’re doing everybody’s. They’re here for a short period of time, they want to have a good time and do as little as possible, and if they can find someone to do the job for them, they will. And when they leave, the next person calls.”

A nation’s embassy is its representation in a foreign land; it’s not just another office building with conference rooms and cubicles. Such a job requires specific considerations.

“There’s a lot of mystique about building an embassy but it’s pretty straight forward,” he says. “They are a client, but we always make them conform to the U.S. Foreign Missions Act which gives us protection. An embassy can declare diplomatic immunity and we can’t attach it [with a lien for payment]. Under the Foreign Missions Act they have to relinquish certain control and give us the right to put a lien on the property.”

In these dynamic times, it helps think ahead: “We got paid by Libya before Gaddafi got control.”

An embassy also reflects the cultural heritage of the nation, which adds to the challenge. “We always respect their national design,” he says. “We ask if there are any motifs they want built into the interior” and they universally do.

One luxury for the builder, in many of these cases: Money is no object for these palaces.

“The United Arab Emirates spent something like $600,000 on the carpet in the ambassador’s office,” Bellingham says. “All silk. We bought a special insurance policy for this carpet, that’s how scared we were.”

And what sort of dwelling does Bellingham and his wife Lynne live in? Has he been inspired by the grand structures his company has built for ambassadors? Actually, no.

The Bellinghams still live in the same brick rambler they moved into in 1978, a year after getting married. They raised three children in the house, situated on an acre in Lincolnia, at the convergence of Annandale and Alexandria. “It’s like living in the middle of the country,” Bellingham says.

Naturally, there have been some improvements to the home.

“The first thing, we chopped the roof off, extended it out and put on another floor,” he says. “It became a beautiful brick Colonial house. When we started, there was a constant procession of cars stopping to look at what we were doing, and now everybody does it.”

“Popping the roof” is a trend, but in those days it was unheard of, but Bellingham wanted to make a point. “It’s something I wanted to show people, that you don’t need to tear houses down.

“One of the biggest problems we have in our industry today is we’re using three times the amount of natural resources that are available in the world. I hate to think what’s going to happen in the future—where are we going to get these materials from? It’s a real concern.

“We need to reuse things, readdress them. I tell people the human skeleton is probably designed to last 150, 200 years; it’s the bits on the outside that die off, and that’s what you have to do with a building. You have to re-skin it and look after it, regenerate it. An American house is very adaptable; you could probably add another 10 stories to it if you wanted to.”

Naturally, there’s an embassy that’s an example.

“Look at the Embassy of the Ukraine,” he says. “It was built in 1789. We took the building, held it up, and put a new parking garage underneath it. We’ve done a lot of jobs like that.”

Piece of cake, right? It is if you’ve been trained.

“Again, if you’ve been trained and you’ve come up through the industry, it’s a lot easier,” he says.

(May 2013)