Kambar Khoshaba had been principal of Lorton’s South County High School for less than two months when the call for help in a bathroom came over the walkie-talkie.

He’d been making rounds in the cafeteria during lunchtime in late August 2022 and arrived at the restroom to find a student slumped and unconscious in a stall. Three people were performing first aid to no avail.

“I have never had the experience of seeing someone in front of me pass away, and that’s what appeared to be happening,” Khoshaba says. “It was easily, hands-down the most traumatic thing I’ve ever gone through.”

Emergency medical technicians arrived and administered naloxone, a drug that reverses an opioid overdose. “He slowly came back,” Khoshaba says.

It’s a scene that repeated itself in schools across Northern Virginia last school year. In February and April, it happened at Alexandria City High School. In March, it was a Fairfax High student. All survived. So did four teens found suffering from overdose symptoms in a bathroom at Arlington’s Wakefield High School on January 31, but a fifth, 14-year-old Sergio Flores, died. The year before, three teens in Prince William County died from overdoses, two within a 48-hour period.

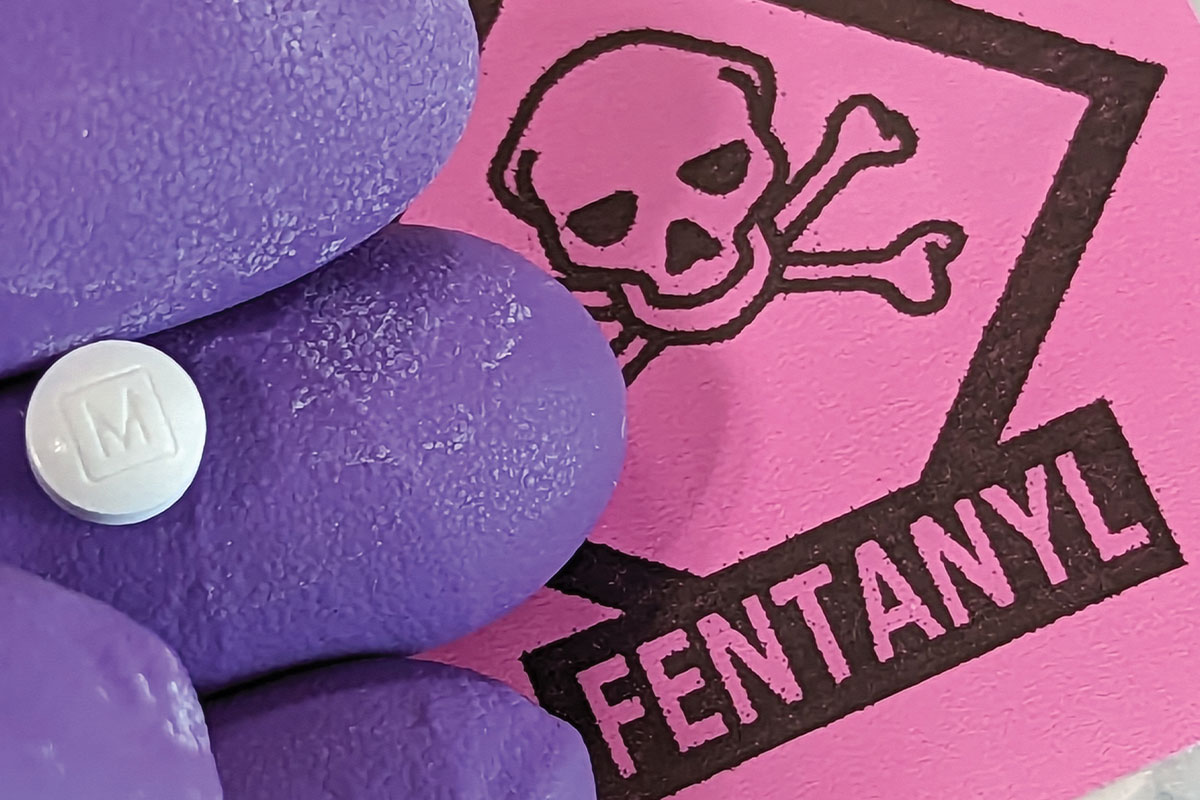

In all cases, authorities either suspected or confirmed fentanyl, a synthetic opioid drug that is up to 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine.

But the problem is likely more widespread.

Jennifer Evans, director of student mental health services for Loudoun County Public Schools, says naloxone has been administered to students at schools, but the cases remain suspected overdoses because the information is protected and up to parents to share with schools.

An Unnatural Killer

A synthetic opioid drug first developed in 1959 as a prescription painkiller, fentanyl has for 10 years increasingly made its way into illicit drugs, manufactured in makeshift labs rather than regulated pharmaceutical facilities. In 2022, it factored into almost 76 percent of fatal overdoses in Virginia and has been the leading cause of unnatural death in the state since 2013, surpassing vehicle collisions and guns.

Nationwide, more than 107,000 people died of drug overdoses and poisoning between January 2021 and January 2022. Sixty-seven percent involved illicitly made opioids, primarily fentanyl, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Fentanyl is already pretty much in everything,” says Ginny Atwood Lovitt, executive director of the Chris Atwood Foundation, which focuses on drug harm reduction and recovery. She and her parents started it in 2013, after she found her younger brother, Christopher, dead of an overdose at age 21.

Teens who think they’re just taking a hit off a joint or swallowing a Percocet may be unknowingly ingesting fentanyl. Today, fentanyl has been linked to vape pens, marijuana, and heroin. Just 2 milligrams — enough to fit on a sharpened pencil tip — is considered potentially lethal, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

In the Fairfax Health District, no one 17 or younger visited an emergency department for a nonfatal overdose in 2019. In 2022, 27 youths did, and within the first three months of 2023, there were 11 such visits. From the start of 2020 through the third quarter of 2022, seven youths died of opioid overdoses, all involving fentanyl.

Of 66 opioid-related overdoses in Loudoun County in 2022, 26 percent involved juveniles, including two deaths. Between January and March 2023, nine opioid-related overdoses were reported, of which 44 percent were juveniles.

In May 2022, Alexandria warned of “a recent spike in suspected fentanyl-related overdoses, especially in school-aged youth who report using a ‘little blue pill’ they believed was Percocet.” Between April 1 and May 1, half of the 12 nonfatal opioid overdoses reported involved people younger than 17.

Schools Fight Back

Northern Virginia schools are working to get the word out about fentanyl’s lethality. While some already provided drug awareness education as early as first grade, many are taking extra steps now.

“We’ve always talked about ‘drugs are bad for you and this is why,’ but unfortunately, with fentanyl, it is such a dangerous situation where one pill or one hit off a vape pen can cause an overdose that we’ve really had to ramp up our messaging,” says Heather Martinsen, behavioral health wellness supervisor at Prince William County’s New Horizons program, which works with schools on substance abuse and behavioral and mental health.

This summer, Prince William County Public Schools announced Fentanyl Exposed, a student-created fentanyl-awareness campaign, geared toward their peers. It includes information on handling overdoses and the legal protections that protect students from prosecution for administering naloxone.

Arlington Public Schools began incorporating fentanyl information into fifth grade health lessons last year and this year will add fourth grade, says Darrell Sampson, executive director of student services. “If you’re a fourth grader or above in Arlington Public Schools, you are getting preventative information about opioids, as well as other drugs, to be able to make informed decisions and understand those risks and harms that exist, particularly with substances like fentanyl,” he says.

LCPS works with Drug Abuse Resistance Education, better known as D.A.R.E., to teach fifth graders about safe medication use. Plus, LCPS’ 19 student assistance specialists speak with sixth, eighth, and 10th graders about drug use dangers and the services available to students struggling with addiction or mental health, says Darren Madison, supervisor of the Office of Student Assistance Services.

Some schools bring in guest speakers. In presentations that Shane Dana, a special agent with the FBI Washington Field Office, has given to students across Northern Virginia, he describes how fentanyl attaches to the brain’s opioid receptors and how that can stop breathing. He also discusses self-medicating alternatives, such as talking to a school counselor.

Still, his biggest concern is that fentanyl’s danger has been minimized.

“Ten years ago, if you were talking to someone who had a serious heroin addiction, they would be terrified if fentanyl was being added to the heroin,” Dana says. “Nowadays, young people are transitioning directly from some of the earlier-stage drugs, like alcohol and marijuana or THC gummies, and going immediately to a fentanyl pill.”

Motivational speaker Sam Anthony Lucania takes a more personal approach. He accidentally overdosed in 2013, after washing down pills, including the opioid Percocet, with alcohol. The former Ashburn resident who now lives in South Carolina has spoken at almost 20 high schools in Fairfax and Loudoun counties.

After his talks, students often share their own stories. “I’m seeing a huge group of troubled kids who doesn’t know what to do,” Lucania says. “I could fill up your entire magazine with DMs that I’ve received from kids telling me how hurt they are, how broken they are, how they feel like nobody will understand.”

Tina DiGiacomo, a New Horizons therapist who has worked with Woodbridge Senior High School students for 23 years, sees progress. “I’ve had so many kids this year who have said things like, ‘I don’t want to do drugs, at least not until I’m 25. My brain is not fully developed yet,’” DiGiacomo says.

Schools are also educating teachers and staff to spot opioid overdose symptoms, such as blue lips or fingernails, clammy skin, and gurgling noises. “[We are] definitely looking to continue to make folks aware of what they should be looking for in relation to any substances that our students might be using,” says Marcia Jackson, chief of student services and equity at Alexandria City Public Schools, where more than 200 employees have been trained.

Naloxone Takes Center Stage

School health rooms across NoVA stock naloxone, and in May, Arlington began allowing high school students to carry it with parental permission.

“We have also recently installed emergency boxes on all the floors of our secondary schools, so our middle schools and high schools have emergency boxes that also have stocked naloxone,” APS’ Sampson says. “We’ve put them in pretty central locations.”

Naloxone’s availability is a good thing, says Dr. Sulman Mirza, a psychiatrist with Inova Health System.

“Will that lead to increases [in use]? No, it will lead to decreases of people dying,” Mirza says. “If we’re telling people how to put condoms on bananas, we should be able to tell people how to do Narcan [brand name for naloxone] into people’s noses.”

It’s important to be realistic about teens’ use of all drugs. While mental health issues in teens have surged, Mirza says “there’s a normal exploration of substances that occurs.”

That’s why “Just Say No” isn’t the right message, Mirza says. Instead, conversations should focus on safety.

“I give a real-world example: When you go to McDonald’s over here versus across the country, you know what you’re getting because quality control is there. With illicit substances, with things that are from that guy around the corner, you don’t know what’s going to be in there — whether it’s a dud, whether it’s super high concentrations of everything, and whether this is the thing that’s going to kill you,” Mirza says.

Dialogue should also be judgment-free. “I always tell parents to ask the question, ‘What’s making you do this? What are you getting from this?’” he says. “That question is saying, ‘I’m here to understand what’s going on, not judge you on what’s going on.’”

Special Agent Dana encourages adults to practice refusal skills with teens. For instance, when in a questionable situation, kids can initiate a ruse, such as calling a trusted adult and saying a predetermined code word to let the person know they need to be picked up.

It Takes a Community

While schools are a natural place to focus drug awareness education and have hosted town hall meetings to inform parents, battling the fentanyl crisis requires a community effort.

“No one entity or person can handle this. Even if we had something on every block, it wouldn’t be enough,” says Katrina King, founder of the Empowered Communities Opioid Project at George Mason University. King is a recovering opioid addict who lost her 20-year-old daughter, Kirstyn, to an overdose in 2011.

Regardless of where teens get the message, King says they “need to know that they’re seen and that we understand their experiences are very real. … They need to reach out and trust someone, and if that person doesn’t work, keep going because life depends on it.”

Feature image, Steve Cukrov/stock.adobe.com

This story originally ran in our August issue. For more stories like this, subscribe to Northern Virginia Magazine.