On April 6, Governor Youngkin signed into law Senate Bill 656, giving parents the ability to review “sexually explicit content” being taught in elementary and middle school curriculums. The bill makes teachers liable to provide nonsexually explicit materials to any student whose parent requests it.

The definition of “sexually explicit” in this bill is lifted from Title 40.1 of Virginia law. According to the code, it is content depicting “nudity, sexual excitement, sexual conduct, sexual intercourse or sadomasochistic abuse.”

The definition is lifted from a code prohibiting child labor in employment that involves “sexually explicit visual material.”

On April 8, the ACLU of Virginia released a statement criticizing the bill, claiming its use of the term “sexually explicit material” is overbroad.

“‘Sexually explicit’ is a vague and overly broad term that could be used to exclude important reading materials like Beloved by Toni Morrison or Romeo and Juliet by Shakespeare,” reads the statement.

Breanna Diaz, policy and advocacy counsel at the ACLU of Virginia, says the new bill will threaten freedom of thought and expression in the classroom.

“We know that this bill will have the impact of prohibiting, or at least dissuading teachers and librarians, from teaching certain books. Maybe books they’ve had in their curriculum for years, as under this new law, these books will be placed under this sexually explicit content list,” Diaz says.

Due to the broadness of definition, Diaz says, parents could potentially raise issues with books written by LGBTQ+ and racially diverse authors, or books whose characters belong to these communities.

“I think we have a lot of concern with where this will lead, and what it will lead to is censorship,” she says.

The ACLU-VA supports what Diaz says is the original intent of the bill: building a better relationship between school boards and parents.

Yet Diaz says that the policy that the bill is enacting has already existed for years in every local school district in Virginia.

In Fairfax County, parents can see what books are available in school libraries in an online database, and can schedule visits to libraries to file formal complaints against specific books. Similar systems exist in nearby Loudoun and Prince William counties.

“This codifies at the state level, a practice that already exists,” Diaz says. “However, it goes one step further, and categorizes particular types of books, which are going to be deemed sexually explicit content, for further rigor, further targeting.”

Diaz says the trust needs to be placed in local teachers and school staff to give children access to age-appropriate literature. Not all parents agree.

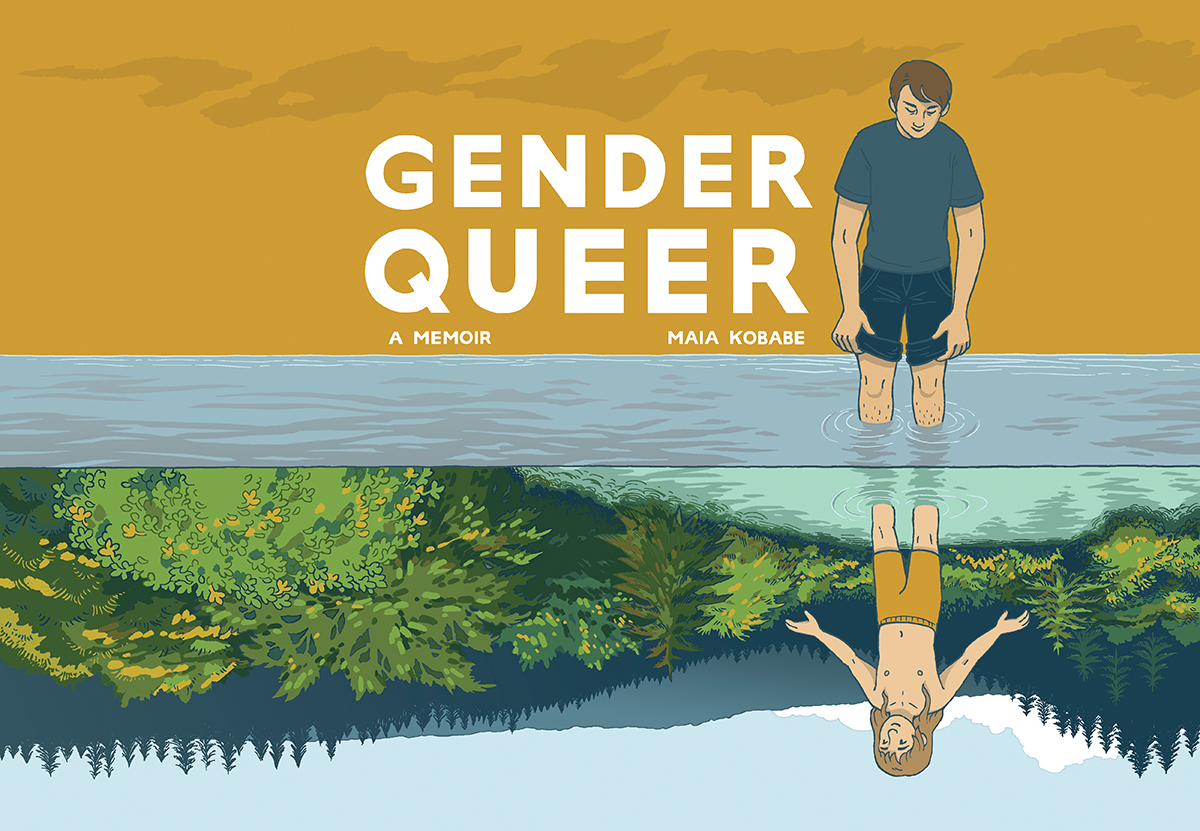

Last September, Fairfax County mother Stacy Langston caused controversy at a school board meeting, where she branded two books in FCPS libraries as “absolute filth.” Langston claimed that the two books, “Lawn Boy” by Jonathan Evison and “Gender Queer: A Memoir” by Maia Kobabe contained graphic sex acts and pedophilia.

Though both books were originally removed after a parent objected to their sexual content, they were eventually put back in circulation in FCPS libraries. The school district cited their “ongoing commitment to provide diverse reading materials that reflect our student population” as the reason for the reinstatement of the books. The school district also stated they found no evidence that the books contained pedophilia, as Langston had claimed.

In Loudoun County Public Schools, “Gender Queer” was banned this past January after school administration received complaints from parents about the book, which depicts topics like masturbation and nudity. The book has not been put back in circulation, and remains banned at LCPS schools.

“The pictorial depictions in this book ran counter to what is appropriate for school,” LCPS Superintendent Scott Ziegler told the Washington Post.

Last November, the Spotsylvania County School Board rescinded a plan they’d made to remove books with “sexually explicit content” from school libraries. The ban was rescinded just over a week after its approval, following student pushback in the form of a petition to remove the ban that garnered over 5,000 signatures.

Diaz says reading books written by diverse authors allows students to feel represented in their classes.

“Access to books by folks of diverse backgrounds and different lived experiences is essential to the full development of our children, to see themselves reflected in their school curriculum, and to have access to different thoughts, ideologies, philosophies that challenge and develop their critical mind,” she says.

Per the requirements of the new law, the Virginia Department of Education must draft and release a model policy by July 31 of this year. All school boards in the state must statutorily adopt the policy by January 1 of next year.

The model policies are open for public comment, as part of the development process of the new law.

Diaz says the ACLU-VA will continue to push back against the bill as it becomes law.

“We fully anticipate in participating in that public comment process,” Diaz says.

For more stories like this, subscribe to our News newsletter.