Carlton Davis looks back at 2011 with the wistful glance of an opportunity just slipped out of reach.

He’s not particularly doleful about it—professionals usually aren’t—but at the peak of his prowess as back-to-back champion of one of the most competitive leagues ever formed in his sport, a third crowning had just escaped his grasp.

“Some guy bested me, which was very unfortunate,” he says. “I made a couple of moves in 2011 to try and go for the three-peat that were probably not in the best interest in the long term of the franchise. I made them anyway. In 2012, I probably should have rebuilt, but since I didn’t win in 2011, I tried again in 2012 and came up shorter than in 2011. Then it was time to rebuild.”

Since then, he’s been lying in wait, carefully plotting his return to the mountaintop.

For almost a decade, Davis has battled in one of the fiercest leagues in one of the fastest-growing sports in the world, fantasy baseball.

Possessed with a deep reverence for our nation’s pastime, Davis is among a group of former Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology students who extended the bounds of fantasy baseball to create one of the most competitive sustained leagues ever imagined, Jefferson League Baseball.

An Unlikely Game

Billion-dollar industries often have inauspicious beginnings, but few start in a French chicken bistro.

Such was the inception of fantasy sports, a game of passion started by ardent fans thirsting for more than just a seat in the stands. Though its early origins date back to the 1950s, the most recognized moment in the birth of fantasy sports is when a group of journalists met at the La Rotisserie Francaise, an East 52nd Street bistro in New York, to devise the rules for the numbers orgy that would become Rotisserie League baseball.

In the ESPN 30 For 30 documentary “Silly Little Game,” the prologue of fantasy sports is laid out by its 10 originators, including writer and editor Daniel Okrent, considered the chief architect of Rotisserie Baseball, a fanaticism married with a statistical dogma that now dominates professional sports.

Now 30 years later, it’s estimated that some 41 million people in the U.S. and Canada alone play fantasy sports, which have grown to include football, hockey, golf, NASCAR racing and countless other sports.

Forbes reported in 2013 that an estimated $15 billion was spent each year on fantasy groups, lauding a whole financial engine built on the bedrock of competition and facilitated by the near-limitless availability of information on the Internet.

It’s from the dawn of the Information Age that a group of former TJ baseball players in Alexandria latched on to the allure of fantasy sports and built a league so extensive, it could exists as a digital alternate universe to Major League Baseball.

“I don’t really compete in anything anymore,” says Davis, a lawyer who works on Capitol Hill. “This keeps the competitive juices flowing. It’s long term. You’re thinking about it in July; you’re thinking about it December, thinking, ‘How can I get better?’ And you just love baseball.”

Like Okrent in the early 1980s, Jefferson League Baseball formed out of an enduring love affair with “The Show” and developed into a decade-and-a-half contest that spans digital dynasties and counts among its former members a current front office executive at a Major League club, who declined to be named.

“[We were] a bunch of athletic nerds, I suppose,” Davis says. “We tried to model it as closely to Major League Baseball as possible. We’d like to think that if we were to take over a Major League front office, we could do so with success.”

Welcome to The Show

The original group of 12 members was formed in Alexandria, and as they progressed towards college, the complexity of the league continued to grow.

“Like a lot of high schoolers our age, we were caught up in the web-based fantasy sports boom, and we had multiple fantasy leagues going on year-round,” Chris McDonald, a naval aviator and the Jefferson League Baseball commissioner, said in an email.

“I’m currently in a rebuilding phase, so I am not as closely keeping track as when I am in a competitive phase…that’s been good for the marriage.”

“Baseball was our favorite, though, and during our senior year we decided we wanted to keep things going beyond our graduation in 2001. So we formed a dynasty league, where you get to keep the same players year after year, which adds to the strategy involved.”

The group decided to implement minor league prospects, allowing their fantasy franchises to construct whole farm systems on which to build dynasties.

“The more and more we dug into the information, the more and more we liked looking at the 400 best prospects in Major League Baseball,” says Dan Hausman, one of the original members and an attorney in Chicago. “It just took a few years to get into place all of the rules that we could try to fit to make it mimic MLB as much as possible.”

Hausman says that included huge minor league systems, amateur drafts, international signings and a salary structure for teams to compete not only in players, but payroll.

“We were into finding out the analysis of players but at the same time delving into salary cap ramifications, how valuable the first five picks of the amateur draft are versus your second round picks or whatever it might be,” he says. “Why bother to do all of this thinking about your fantasy team in that level of sophistication if you don’t have a league that matches that?”

So to construct the league in its fully realized form, the members decided to draft a constitution. As many of the members would eventually be attending law school at the University of Virginia, the document would be binding and read like a Magna Carta of fantasy baseball statutes.

Prior to implementing the Jefferson Fantasy Baseball League’s salary structure of fantasy millions, the group had been governed by an 18-article constitution written during the members’ last year of high school.

Realizing a more ambitious league would require a more ambitious charter, in 2005 the group set out for a weekend in Philadelphia with the hopes of forming a more perfect union.

“We had a few league members enrolled at UPenn at the time, so near the end of their senior year we decided there was no better place to rewrite the league constitution than Philadelphia,” McDonald said. “After three days of beer pong and brainstorming, we came up with a new living document and a new name—Jefferson League Baseball, or JLB.”

The current constitution now contains 24 articles covering everything from a luxury tax, multiple drafts, arbitration and contract buyouts.

The JLB teams draft the same amateur players the majors do. They have a free agency period, foreign player drafts, a luxury tax and multi-year player contracts. Though built and maintained in the digital world, the JLB might as well be a professional league existing in a parallel universe.

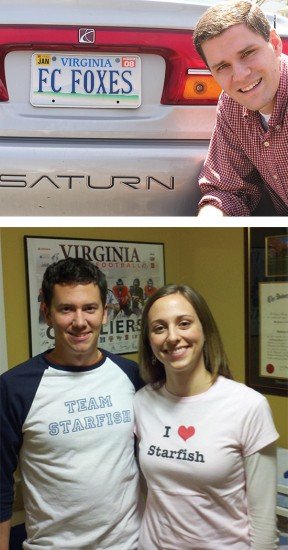

To enter the league, the hopeful applicant must write an essay “to prove his dedication and commitment to Jefferson League Baseball” and be approved by 75 percent of the owners. The club names must be alliterative, hence members like the Reston Roundabouts, Great Falls Grenades and Falls Church Foxes.

Of the league’s 12 teams, six were created by the charter members. The remaining members lobbied for the coveted open spots through a rigorous application process. Because several members of the league have careers in law, investment banking and other high-level professions, applications have included PowerPoint presentations and detailed investment plans for the anticipated franchise.

The secret to success in the JLB seems to be not trying to win it all every season, though McDonald admits that many owners do, but rather building the farm system and setting up favorable conditions for the future. In a league this competitive, it’s not unusual for a team to be in contention for maybe two or three seasons before having to unload its high-priced players and rebuild through its minor league prospects.

“We just had two owners negotiate a big trade while one was in Southwest Asia on business and the other was on vacation in Central America.”

“In my line of work, naval aviation, we also tend to focus a lot on risk management, and I’ve applied some of those principles to how I manage the Sterling Starfish as well,” McDonald said. “I’ve found some success by emphasizing a deeper roster that was able to withstand disappointing years from expected key contributors.”

Davis says the league heats up on January 1, when agency opens, and stays active until spring training starts in March, requiring dedicated watch over player information and performance, all leading up to opening day.

“During the season, I probably spend an hour a day [on JLB],” he says. “It’s not always an hour in a row. I don’t know what I would do at work if the league didn’t exist, quite frankly.”

Since his run in 2009 and 2010, Davis has been quietly building the Falls Church Foxes back to prominence. But during the competitive stretches, the monastic dedication that the league requires can be all-encompassing.

“I’m sure I’m not the only guy this happened to, but it’s definitely caused some stress in the marriage,” he says. “I’m currently in a rebuilding phase, so I am not as closely keeping track as when I am in a competitive phase, so that’s been good for the marriage.”

McDonald said the reverence that team owners have for the JLB can be shocking, where dedication to the spirit of competition can drift into other aspects of members’ lives.

“A couple guys plan their family vacations around our offseason free agency period,” he said. “We just had two owners negotiate a big trade while one was in Southwest Asia on business and the other was on vacation in Central America. Everyone always seems to find time for JLB.”

A Sport and a Pastime

The truly unique aspect of the JLB is its continuity. As years pass and social networks that were once as dense as spring foliage start to thin, when friendships that were separated by miles become distanced by area codes, states and even continents, the league remains.

“It seems like most people that are fortunate enough to have lifelong friends meet those friends in college, but I happened to meet mine at TJ, and JLB’s been a great vehicle for keeping those relationships going,” McDonald said. “My best man was a JLB owner, as were two of my groomsmen.

“We may start a conversation talking about a trade or a prospect, but eventually it moves towards family, work and real life. It’s tough to keep in touch when you move away, even in the age of social media. JLB has helped us remain a tightly knit group, and I’m grateful for that.”

“Real life can get monotonous, which makes the escape even more alluring.”

The league isn’t a side project meant to burn idle minutes in between the responsibilities of adulthood. It’s woven into the fabric of each member’s life.

The members gather each November around Thanksgiving for the league’s winter meetings, where each team announces its roster plans for the following season. It’s the one time all the members are in the same place, meeting at the same apartment.

When Davis got married in 2010, he also claimed the JLB title. The couple’s wedding reception was held in Nationals Park in Washington, D.C., with the JLB trophy, affectionately called “The Joe,” proudly displayed.

The league is also a way to remember those the group has lost, like Mike Durgala, a former member and Johns Hopkins assistant baseball coach who was tragically killed in a car accident in 2006. The award for the league’s best general manager bears his name.

The league is a challenge, a gauntlet dropped to test your wits, to duel against friends you’ve know most of your adult life.

“Everyone in the league is very smart. I’m sure we think that about all of our friends,” Davis says. “Some of the guys in the league

are some of the smartest people I know, hands down.”

Most of all, the league is life, or what members want from it once bills have been paid and careers and responsibilities are managed. The league is where creativity and passion are rewarded, where tedium recedes and every day is opening day.

“Why we’re so committed to it is a good question and one that I’ve often pondered,” McDonald said. “I suppose it’s because it’s a well-designed, entertaining escape from reality.

“Real life can get monotonous, maybe even more so as we progress in our careers, which makes the escape even more alluring. JLB is our collective harmless vice.”-Carten Cordell

(May 2015)