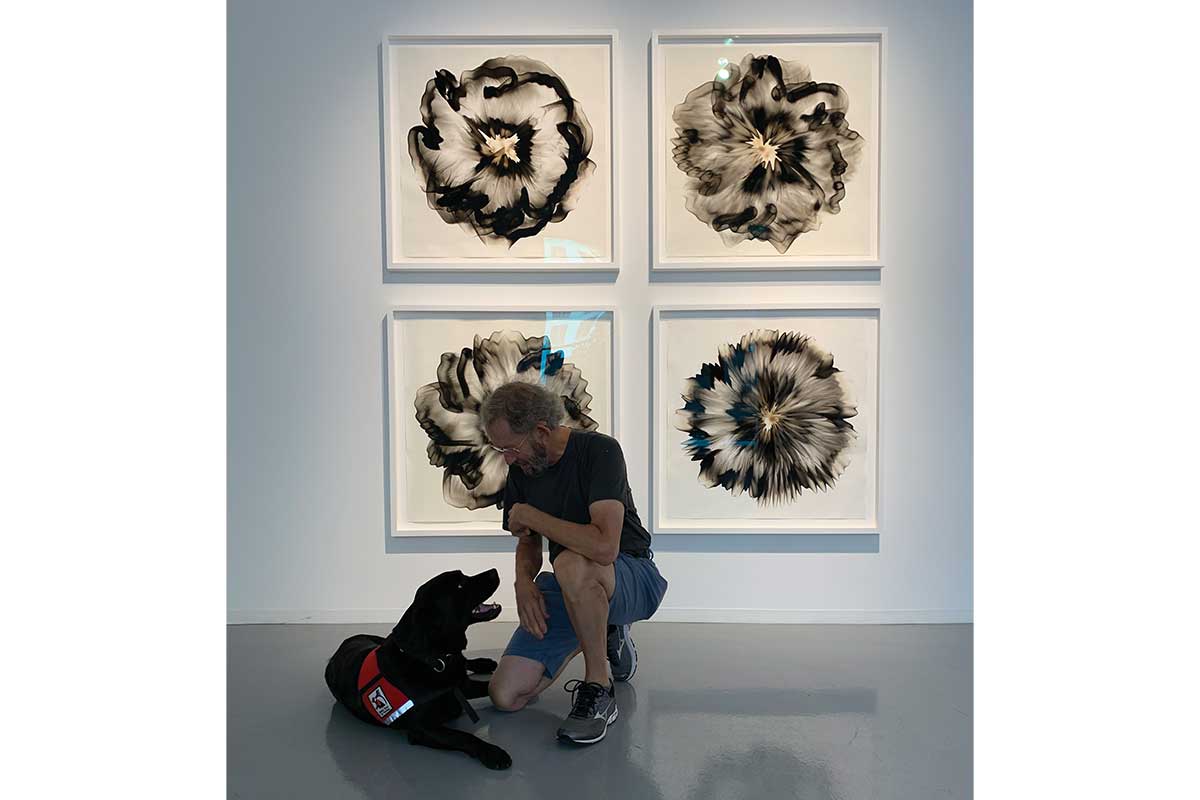

Dennis Lee Mitchell, a visual artist based in Old Town Alexandria, sits next to his loyal companion Andre, a remarkably well-behaved black Labrador retriever. Andre is Mitchell’s service dog; Mitchell has Type 1 diabetes. “When my glucose levels are getting low, he nudges my leg with his nose,” Mitchell says.

All over Mitchell’s warehouse studio are large, stiff sheets of paper with intricate blooming abstractions on them: These are drafts of Mitchell’s work, and they’re not for sale. But they serve as important reference material because Mitchell works with fire — and fire doesn’t always listen to the artist. They help him capture methods for his next piece and observe the intricacies of how smoke behaves when put to paper.

“Smoke doesn’t exactly go where you want it to go, so it’s a risk to start with — but sometimes that risk actually pays off,” Mitchell says. “Other times, it just looks terrible.”

Accidental Art Form

To make his art, Mitchell wears a welder’s mask and fires up an acetylene torch dosed with colored powder. The paper he uses is coated with ground — a type of adhesive made from marble dust that absorbs the smoke from the blowtorch into its textured finish so that soot doesn’t rub off of the paper. Mitchell uses the adhesive to trap the smoke in the pattern it makes when it hits the paper’s surface.

Mitchell says he discovered this art form by accident, as cliché as that may sound. He was a professor of ceramics, and one day he started working with clay using a blowtorch, instead of a kiln, welding pieces together. “I had been working with clay for many years, and then, in the back of my mind, I heard a voice say, ‘Go somewhere else,’ so I did,” he says. “I always work in ways that are not typical. If somebody else is doing something one way, I’ll let them do it — I assume they can do a better job.”

He discovered the beauty of working with smoke while he tested his torch on clay. “When you’re using a blowtorch, if you adjust the flame, you’re going to get more or less smoke. I adjusted it a little bit and tried it on a sheet of paper before using it on the clay, and the effect was just marvelous,” he says. “I essentially quit making things in clay and started working only with smoke on paper. A few weeks later, my dealer walked in and said, ‘What are these?’ And then she said, ‘We have to show these.’ And I just started working.”

That was 12 years ago, and Mitchell has been expanding on his art form ever since. Mitchell’s work is represented by galleries all over the country. “Right now, I’m making long lines of color with the smoke and then tearing them in half and finding another match for the other side,” he says. “The result looks something like trees, maybe, but they’re more like lines with two halves that come together to produce a spine by that torn edge.”

Trial and Error

Discovering something accidentally is relatively easy, but making a career out of that discovery takes more work. Mitchell’s pieces initially look like floral patterns, but the more you look at them, the more you’re consumed by negative space. “They started out being voids, and I’d make them by putting the paper on a turning wheel and applying the smoke from the torch randomly. Then everybody started telling me that they were flowers, but I never intended for them to be floral or anything. I just started taking action: moving the hand, moving my body, and swirling the smoke into the paper. I intended to disorient myself by making the process less predictable.”

The whirlpool-like smoke formations are difficult to look away from because they seem to go deeper than the surface of the paper. “The work is disorienting because it reaches down to another level when you look at it,” Mitchell says. “Smoke isn’t permanent at all. It’s intangible. It seems to reside only momentarily on the surface of the paper, even if you apply it directly to that surface — and when the piece is completed, the smoke looks as if it will be there only for a little while.”

The individual pieces vary widely, but they have a consistent look and feel and present like the result of a systematized approach. “The actual action doesn’t take very long,” Mitchell says. “But there are a lot of times I’ll make something, put it aside, and look at it a few days later and add to it. If I come in three days in a row and I like the same thing, then it’s finished, but typically I make some kind of tweak to the piece after I set it aside. On average, I make about 15 to 20 drafts for each work I select.”

Infrequently, a small piece can take as little as five minutes to make. And then, some pieces take more than a year. Mitchell gestures to the front of the studio, where he has pieced together blue and green petals that span the wall. “That, I’ve been working on for a year and a half.” His works range in price from $7,500 to $60,000, which not all potential customers are thrilled with.

“People have really confronted me on the price, and they’ve given me some difficulty because they think anything that can be done so quickly is easy to produce,” he says. “They think they’re getting screwed because they’re paying a lot of money for the piece. I can almost see it coming from somebody as I’m talking to them. But if you give just anyone a blowtorch and a piece of paper, they’d burn the place down.”

On that note, we glance over at Andre. He appears to be sleeping with his eyes open, curled up in his bed with his nose wedged into the fabric. He hasn’t moved a muscle the entire time we have been talking. In contrast to the exhilarating nature of Mitchell’s work, Andre’s presence provides a soothing stability.

Perhaps it also helps Mitchell stay grounded and connected to his art. “My work is a result of my connection with nature — the fact that nothing lasts forever,” Mitchell says. “Smoke is the point where something becomes dust. It’s where the magic happens.”

For more information, go to dennisleemitchell.com.

Feature image by Craig Staley

This story originally ran in our June issue. For more stories like this, subscribe to Northern Virginia Magazine.