On March 12, 1987, Kenneth Nixon Jr. was born in Arlington’s Garfield Apartments. His father found him lying on the floor, wrapped in newspapers. Sitting in the corner was his mother, Ramona, vacant and emotionless.

She had bitten off part of the umbilical cord.

Nixon’s father quickly called the paramedics, and both baby and mother were rushed to the hospital and treated. Shockingly, Nixon was released into his mother’s care, but he was ultimately taken away from her. His childhood continued to bring moments of pain and tragedy, as he watched his mother continue to struggle with severe mental illness. He moved from town to town, from the home of one family member to another, stuck in an enduring cycle of trauma. His mother encountered heartbreaking mental illness, addiction, incarceration, and hospitalization.

“Growing up, as a child and into teenage years, there was so much uncertainty — questions I had,” Nixon says. “Like, ‘Why do I have to be the one that doesn’t have a mother around?’ And not feeling I had a place, or a sense of identity, or being loved in a way that I thought was necessary.”

Turning the Tide

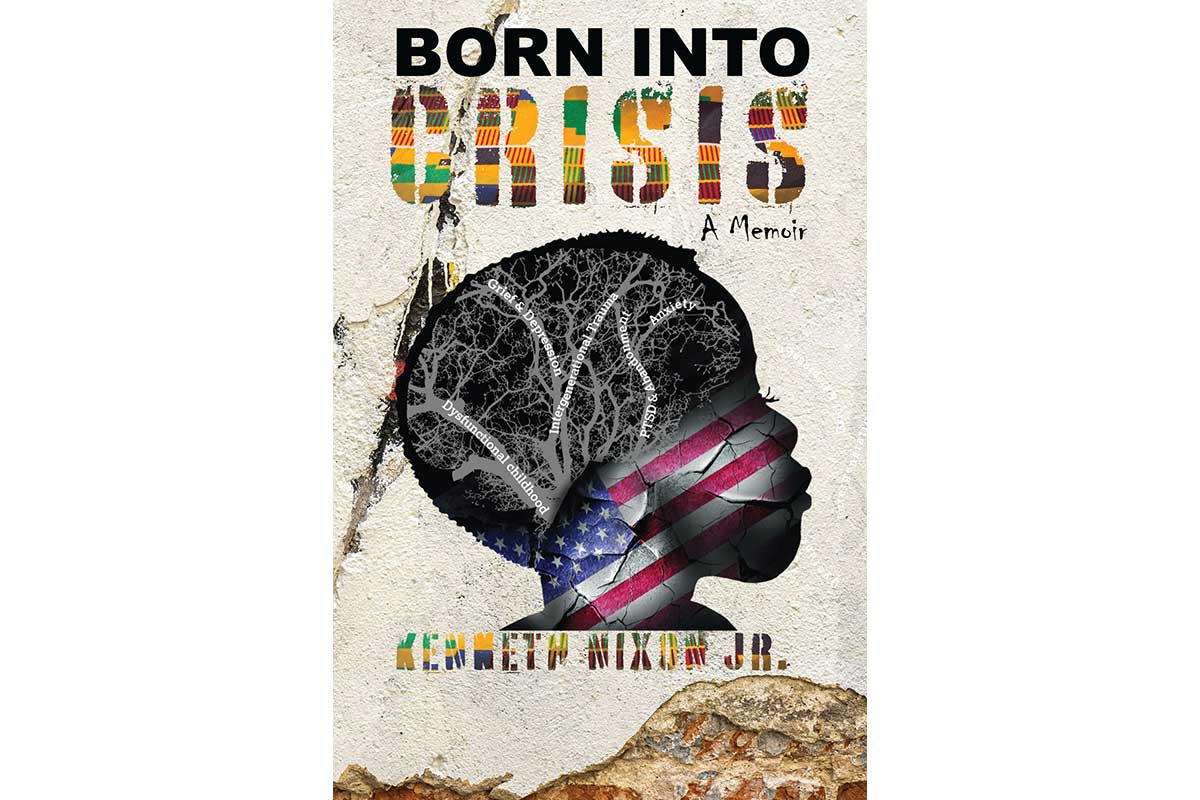

Now a community organizer and pastor at First Baptist Church of Manassas, Nixon wrote about his tumultuous upbringing in his new memoir, Born Into Crisis. Convinced his tragic childhood prepared him to advocate for mental health services today, he hypothesized in his book’s introduction: “I can’t help but feel that my life has been predetermined by the events that occurred on the day of my birth. … I was destined to end up right where I am today, advocating for the transformation of the mental health system in America.”

Nixon’s book is his most recent effort to improve the region’s mental health landscape. For the past decade, he has served as a community advocate with an organization called VOICE, or Virginians Organized for Interfaith Community Engagement, helping lead several statewide and local campaigns as a clergy leader and community organizer.

“There’s sort of a rare breed of leader who wants to help bring meaning to the difficulty and suffering they have experienced,” says James Pearlstein, co-lead organizer for VOICE. “Whatever it is inside of Rev. Nixon that has given him the strength to want to make sure that his mom’s suffering and that which he endured should not be something we keep passing on to other generations. I do think it really lights a fire inside of him.”

VOICE, composed of 42 member institutions, ignites community action on key issues in Prince William, Fairfax, and Arlington counties and Alexandria. It represents more than 200,000 residents. Nixon stepped up to serve on VOICE’s board of directors fueled by his passion to bring tangible change to access for mental health resources in the community.

“The best witness to any truth is those who have lived it,” says Keith Savage, senior pastor at First Baptist Church of Manassas. “He’s a living witness to it from birth — he’s seen it all, so he is a true expert.”

With Nixon’s help, VOICE successfully advocated for a new crisis health center in Prince William County. The county will spend $15.2 million for a building at Potomac Mills mall that will be turned into a community-based crisis receiving center. So far, the project has raised $18.7 million in one-time funding and is awaiting an additional $2 million in federal funding. At least $4.8 million in ongoing funding also has been committed, according to Rachel Johnson, the county spokeswoman.

“That is a tangible impact that Kenneth Nixon has made in this community that’s going to affect thousands of people for years to come,” says Savage.

Expected to open in the fall of 2024, the crisis receiving center will be the first of its kind in Virginia, offering a variety of mental health services. Nixon says his organization claims some wins at the state level as well.

“Last year, we won about $12 million for building crisis receiving centers throughout the commonwealth,” he says. “And we were also able to secure an additional $20 million for emergency psychiatric alternatives in hospital settings for hospitals to be able to try to expand in some rural underserved communities that can’t have a full-fledged crisis receiving center.”

Work to secure that funding was done in collaboration with the Virginia Association of Chiefs of Police and the Virginia Hospital and Healthcare Association.

With high praise from colleagues for profound influence in powerful circles, Nixon hopes to help transform the state of mental health in the U.S. through his role at VOICE.

“My voice is actually going to get louder until people fully realize, especially those in power, that people who have a mental health challenge and mental illness didn’t choose to be that way, but how we respond to it is completely our choice,” he says. “It’s time for us collectively to begin to invest in health and wellness that is not just physical, but mental as well.”

Call to Action

In Born Into Crisis, Nixon shares his personal story. He divides the book into two sections: The first part shows his life experience coping with his mother’s mental illness, and the second part outlines a call to action. Hot-button topics, like decriminalizing mental health and addiction, recognizing types of trauma, and advocating for policy change, play a pivotal role in seeing positive change, he says.

“The big takeaway is that we need to move mental health to a humane system of treatment,” Nixon says. “The second takeaway for individuals is that there is power in their story, and they have the ability to make systemic change.”

Nixon notes that his now-deceased mother was one of millions of Americans caught in a vicious cycle: juggling the demons of mental illness, addiction, incarceration, and ineffective hospitalization. This recipe for disaster inflicts insurmountable stress on families.

“It’s a national issue, a state issue; it’s a county issue, a community, sidewalk issue, school issue — you name it — mental illness is on the radar for everyone right now,” says Savage.

Nixon’s interactions with VOICE convinced him that interfaith community organizations wield power. With positive change as the common denominator, he says people from various faiths are more likely to assemble, united with a common goal. Nixon has witnessed synergistic results — he says last year, the commonwealth of Virginia spent nothing for mental health crisis centers’ ongoing funding. In part as a result of VOICE’s intensive advocacy efforts, Virginia’s current budget will reflect a new prioritization of crisis centers.

“It’s not enough, but it will go from zero to close to $70 million,” Nixon says.

Striking for Change

Nixon also reveals in his book that, in large part due to his dysfunctional upbringing, he suffers from anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. He says the epidemic of mental illness in American youth needs to be addressed and that the stigma around mental health challenges needs to disappear.

“It’s OK not to be OK,” Nixon says. “If you bottle up all of your emotions — if you’re constantly smiling on the outside but crying internally, those are silent killers; it will wear your body down physically and mentally.”

With the publishing of his memoir, Nixon adds to his arsenal of strategies to change the mindset and status quo surrounding mental health services. His personal perspective commands respect and consideration, colleagues say.

“The most important thing I think people should know about Kenneth Nixon,” says Savage, “[is] he has wisdom beyond his years — and it’s all filled with love.”

Feature image by Candace Boissy

This story originally ran in our June issue. For more stories like this, subscribe to Northern Virginia Magazine.