At Fairfax City’s Ratcliffe Park, children run in circles around Andrew Mallon’s sculpture. Some grab it for leverage as they make sharp turns. Others try to climb it. No one tells them to stop.

Whereas most works of art come with stern warnings for admirers to keep their hands off, Mallon’s sculpture, Whimsical Treehouse, is not most works of art. Mallon is a chainsaw artist whose medium is tree stumps.

“It’s just a great way to spread the art through the community,” says Mallon, who grew up in Arlington’s Ashton Heights neighborhood. “They’re not hidden in somebody’s house. Probably about 50 percent of the jobs that I do are in the front yard, somewhere where the public can see them. I also do a lot of parks, which, obviously, are out in public. The other 50 percent are backyard trees.”

He estimates that he has carved 60 to 70 trees in Northern Virginia. These include an oak that he turned into a 6-foot-tall lighthouse, another oak that became a chimney at Big Chimneys Park in Falls Church, and a 128-year-old tulip poplar whose now-shortened trunk is forever flanked by critters native to the area where it’s rooted outside Annandale’s Hidden Oaks Nature Center.

For Ratcliffe Park, the task was turning the remaining 12 feet of a massive sycamore into … well, something. “I told him that I wanted it to be fun and that I wanted him to use local creatures, but otherwise, I let him do what the tree told him to do,” says Megan DuBois, cultural arts manager at Fairfax City Parks and Recreation. “The really fun part for the community was, since it was in the middle of such an active playground, they got to watch it from the ground up. They watched it go from a tree and then watched him work and got to talk to him.”

More recently, Mallon has gained a bigger audience. He joined A Cut Above, a TV series on the Discovery Channel that brought together 12 chainsaw carvers from around the world for a competition. It debuted in October and ran for 12 episodes, with one artist getting eliminated in each one.

It was filmed last spring in Squamish, British Columbia, in Canada. Mallon says he was there for about six weeks. “The experience was great,” he says. “Getting to carve day after day on a competitive level was rigorous. And it was definitely a fun experience getting to carve with that caliber of carver day after day. I learned a lot about staying strong, [but] … it really took a toll on us just being away from the family. I do have two young girls, and they’re both daddy’s girls, so they definitely missed me. And that made it really hard.”

Mallon did quite well in the competition — he was eliminated after the 10th episode.

Finding His Way

One of 10 children, Mallon attended Arlington’s Washington-Liberty High School, where art was his favorite class. But a learning disability — dyslexia — meant he had to spend extra time on academics.

“I actually signed up for a sculpture class my freshman year of high school, but I couldn’t take it because I had to do an extra study course,” says Mallon, who now lives in Winchester with his wife and daughters, who are ages 4 and 2.

Determined to work with his hands, he took carpentry classes after school at the Arlington Career Center. After graduation, he became a full-time carpenter, working for several local remodeling companies for 15 years.

In 2012, he found himself whittling small pieces of wood. “I was like, ‘Wow, this is fun. I’ve got something here,’” Mallon says. “I started doing it more and realized that I really had the vision to make anything I wanted.”

He’d seen chainsaw artists on TV, and something clicked. “I said, ‘You know what? That’s just another tool in my hand. I can do that,'” Mallon says. “I’d hardly ever used the chainsaw, but I knew that it’s just another tool. … So I decided one day I was going to be a chainsaw artist, and I haven’t really looked back since.”

He enrolled in a one-on-one class with Rick Boni, who offers training through Appalachian Arts Studio in Ridgway, Pennsylvania. A session begins with safety and basic saw instruction, including blade sharpening and adjusting the machine for use in carving. For instance, chainsaw artists put carving bars on the tool. They lack a roller nose on the end of the bar to minimize kickback and allow for a smaller tip to be used. Tips come in several sizes and affect the level of detail an artist can achieve. A dime tip, for example, is a little bigger than the size of a dime to allow for precision.

Then, they start carving, says Boni, who teaches about five carvers per year from his workshop and has taught large groups in Japan and Europe. “I carve one right beside them so they can watch every cut I make,” he says.

He and Mallon spent two days together. On the first day, they made a bear coming out of a log, and on the second day, they created an owl on a stump. Each took about four hours.

“When I was lucky enough to give instruction to [Mallon], he had all the right stuff in motion already,” Boni continues. Mallon “was the easiest guy I ever taught. He just took right to it.”

The “right stuff” includes strength, coordination, and artistic ability. “It’s sort of like art, shop, and gym,” Boni says of chainsaw artistry. “It’s pretty hard work.”

Inside the Job

In 2016, Mallon opened AM Sculptures and officially made his hobby his full-time job. Since then, he has traveled the world, attending chainsaw carving competitions and shows.

Although he works with all types of trees, the majority of the big ones that are dying in Northern Virginia are oaks, he says.

“All the trees that I work with are trees that are dead or dying,” Mallon says, adding that it’s up to the landowner to work with an arborist to assess the tree’s health. “The area that we live in … these oak trees were planted back when these neighborhoods first got going, and they’re all at the end of their life.”

White oaks are the easiest to carve and last longer than red oaks, he says, but his favorite to work with is white pine because it’s softer and doesn’t crack as much as the hardwoods.

Many of his pieces draw from nature, featuring birds and animals common in Northern Virginia, but he prefers to do abstract pieces. “That’s really where my passion is, what I love and enjoy doing the most,” Mallon says.

In the fall, he was working on a piece in Vienna, which he planned to make look like a flame rising from the tree base. “There’s one over in McLean that’s like this big twist, where I added in stair treads, and it almost looks like this stairway just winding up in the middle of the yard,” Mallon says. “That’s probably one of my favorites.”

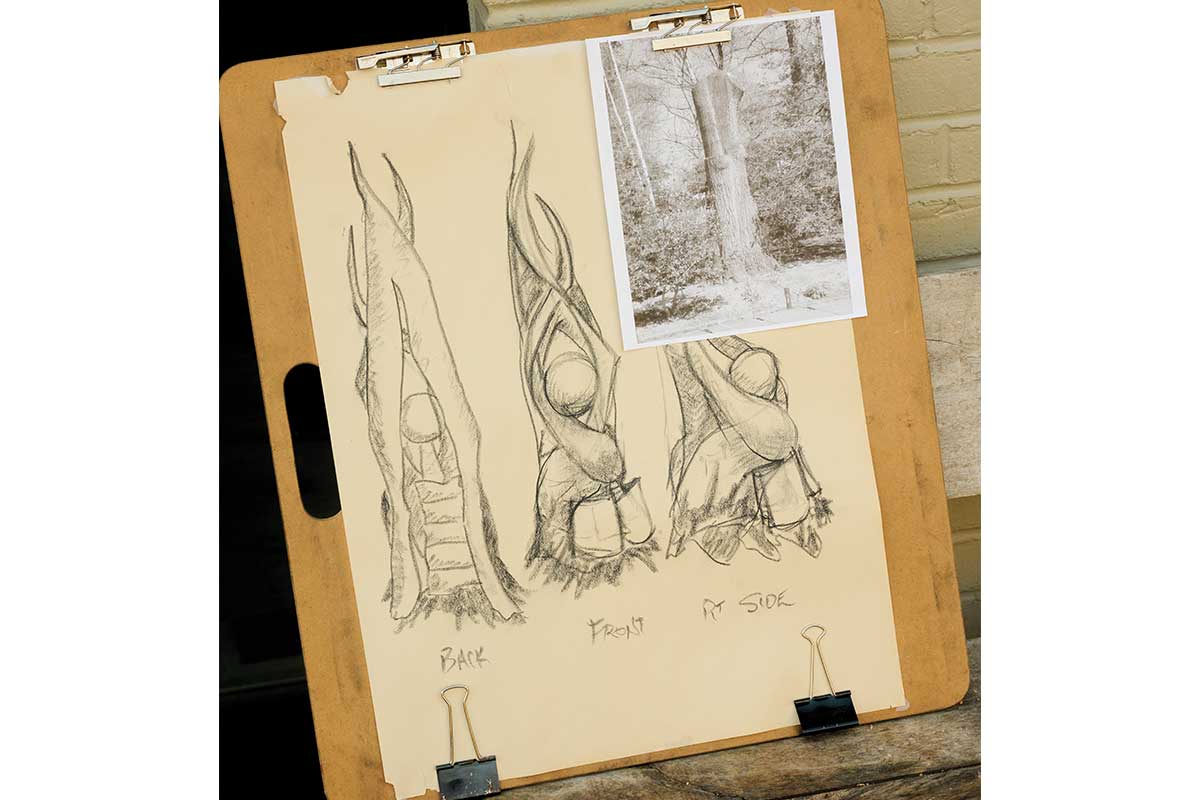

Before he fires up one of his Stihl chainsaws and starts cutting, he works with customers to understand their likes, dislikes, and interests. “I try to take a couple ideas from them and then turn it into something that I think fits for them,” he says. “We go over different ideas, and we settle on one. If I have to, I’ll do a light little sketch for them, but generally, I’ll just spray paint on the tree a couple marks and let them get a basic idea.”

The amount of detail he can achieve with such an unwieldy tool is stunning — even to Mallon. “We can get a very fine detail with the chainsaws, and then we pull out some other little grinders and can put more detail, smaller detail, clean them up smooth, if we would like,” he says. “That’s the magic of chainsaw art: big and fast and amazing.”

The average project — a 3-foot-tall oak stump — costs $4,000 to $5,000 and takes him three to four days to carve. Mallon makes about three to four sculptures per month, mainly between March and December because the sealant he applies to protect his sculptures doesn’t work in temperatures below 40 degrees.

He and his family moved to Winchester from Falls Church three years ago because, “I need somewhere I can make noise,” Mallon says. “Chainsaws are very loud. I needed the space.”

Now he’s got 2 acres of it, part of which he devoted to his workshop, which he built himself during the

COVID-19 lockdown in 2020. Although he calls it “really nice,” he prefers to work in the great outdoors.

“I’m 40. I can climb scaffolding for another five or 10 years” to reach those tall projects, he says. “Later on in life, I can stay in my shop and just do work in my shop.”

Eventually, he wants to open a sculpture garden and trail where he can create large-scale sculptures like the 20-foot-tall Bigfoot that he made using scraps from a sawmill. “I’d like to do that with some other animals, like on a nice mountain trail — some big sculptures and then some smaller chainsaw art along the trail.”

In Fairfax City, there are no immediate plans to commission Mallon to carve another stump, but DuBois says it’s always an option. “It was such a fun project,” she says. “I love … seeing a kid get really excited when they notice something they hadn’t before, whether they see the squirrel or the cheeky bear — whatever makes them happy. And when they interact with the piece, that makes me really happy.”

Mallon feels fortunate that others can share in his passion in their own way. “Finding chainsaw art, it was just the perfect medium for me,” he says. “I really like getting out there and putting my art all over different neighborhoods.”

Feature photo by Shannon Ayres

This story originally ran in our February issue. For more stories like this, subscribe to our monthly magazine.