There’s a reason the old adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” remains in American vernacular—it’s true. The stories told through photography have the power to spark emotional responses, change opinions and motivate action. But it may be the eyes behind the lens that are the most important part. Photographers, after all, determine what stories are told by their cameras. Annie Griffiths brings a specific point of view to her projects that, in her words, “only a woman can.”

Sometimes the best things in life come from a combination of hard work and dumb luck. Photographer Annie Griffiths has, in part, inclement weather to thank for her first assignment from National Geographic.

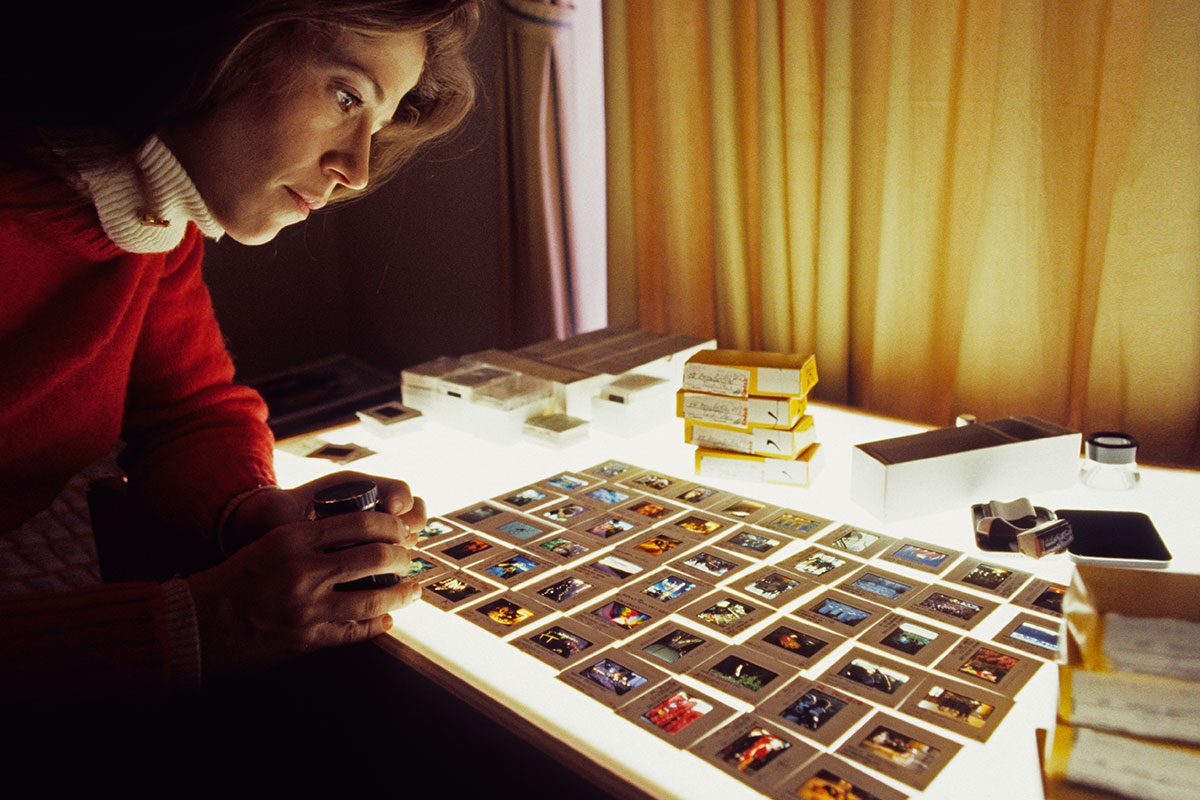

Griffiths was working her first job at a regional, daily newspaper in southern Minnesota. “I was in the dark room on a regular day, and the phone rang and I answered it,” Griffiths says. “It was the director of photography at National Geographic. He needed a really good hail-damage picture, and he saw that there was a big hailstorm in Minnesota. He called to see if I could run out quickly and get a hail picture. So I did.”

It was 1976. Griffiths was in her early 20s at the time and “it gave me the courage to put a portfolio and a story proposal together about a year later to see if I could knock on the door,” she says. “I never dreamed they’d say yes to the very first thing, but they did and I’ve been working with them for a number of years.” The accomplishment wasn’t just one of triumph for a young 20-something, but for women in photography as a whole. Why? At the time, Griffiths was one of the first (and only) female contract photographers on the National Geographic team.

Widening the Frame

“I became a part of a core group of photographers who were regular contributors [to National Geographic],” Griffiths says. But it was her female perspective that distinguished her from the crowd.

“Being the first woman, it was just really scary and lonely,” Griffiths says. “My colleagues were wonderful to me, but I very quickly began to realize how many stories were underreported or not recorded at all because most photographers were men.”

Griffiths quickly learned that being the only woman in the group was an advantage. “I would, first of all, know what the stories were, and then I would get access,” she says. “I’d get access to women’s homes, their kitchens, their reality, their emotions. In any part of the world where there’s gender separation, men are not going to be able to get the same kind of level of permissions that a woman can because their worlds are very different.”

Throughout Griffiths’ National Geographic portfolio, a main common thread is seen: Women, as they are in their communities, shine through the photos. They are not just mothers and wives, but farmers, creative makers, healers. They’re the seams that hold the fabric of their communities together. They’re Brazilian, Indonesian, Tanzanian, Indian, Peruvian … the list goes on.

Capturing Reality

Griffiths has traveled to more than 150 countries in her career, working to humanize the people and cultures she photographs by showing life as it is.

“The journalistic imperative is you do not alter reality,” Griffiths says. “You don’t want to create something that didn’t happen or alter something that did. So, 90% of the ‘people work’ that I do is just candid. You have to be ready as soon as you see the shot. The things that people are directing are never as real as things that just happen.”

So often though, in a 24/7 breaking news cycle, people in developing countries are portrayed as victims to a Western audience. “I spent so much time with women in Third World countries, and I became appalled at how they were portrayed in Western and mainstream media,” Griffiths says. “Media has become mostly reactive; breaking news is U.S.-centric. The stories that are covering poor women are usually painting them as helpless victims. People would say, ‘Oh, these women just have the worst lives.’”

It was Griffiths’ goal to change that point of view, because it simply wasn’t what she saw when she interacted with women in developing countries, and wasn’t how those women interacted within their communities. “Women are the centerpiece of most communities,” Griffiths says. “They’re the caretakers. They allow life to go on in their communities, even if they come up against obstacles.”

Images captured by Griffiths show women taking care of babies, grieving and mourning the loss of family members, working on farmland, embracing friends, collecting water, applying makeup, praying. It’s a true glimpse into lives that most Westerners will never get to experience firsthand, without using film as cultural imperialism. Instead, Griffiths shows her subjects as they are, going about their daily lives.

As a result of the honesty captured in her images, Griffiths’ work has culminated in several awards from prestigious organizations, including the National Press Photographers Association, the Associated Press, the National Organization of Women, The University of Minnesota and the White House News Photographers Association.

Passion Project

Over four decades after her first National Geographic assignment, Griffiths continues to travel all over the world—camera in tow, of course—to produce awestriking photos for the publication (still primarily focusing on women in developing countries), as well as volunteering her time through her organization, Ripple Effect Images.

Working pro bono, Griffiths is the founder and executive producer of Ripple Effect Images, a collective of photographers who document programs that are empowering women and girls throughout the developing world.

Nonprofits and initiatives that benefit women and girls around the world are selected by Ripple Effect Images, which then creates film and images to cover the organizations’ work. The nonprofits then use the imagery for fundraising, as well as to provide advocacy and education, and to promote their brands’ successful projects.

“The reason I started Ripple Effect Images is because I have been so honored to be in these women’s midst,” Griffiths says. “I’m so in awe of their intelligence, their resourcefulness, their spirit. I recognize if people only saw them as victims, it would never occur to them to invest in them.”

Ripple Effect Images not only promotes the lives of women, but is also led by an all-women team. “I observed that women, when they work together, there’s this tremendous light between them,” Griffiths says. “Women in general are very social, communal. So, I called my girlfriends and said, ‘We’re all out there seeing what these women can do. Why don’t we learn from them and work together?’ They all said yes.”

“Ripple Effect is a collective of extraordinary photographers, filmmakers and writers,” Griffiths continues. “We document successes and solutions to empower women and their kids. We find programs that we think are really successful and innovative, we create a film for them and images to cover their work and then they use that to tell their own story. In the past, nonprofits have just had sad piles of pictures that some warm body with an iPhone took, and they’re not compelling. We create compelling storytelling materials to leverage the foundations.”

The material created by Ripple Effect Images can be found on websites, being used as assets at fundraisers, in presentations to corporations and more. As of press time, Ripple Effect Images has worked with over 32 aid organizations to create 50 films and 45,000-plus images, helping to raise more than $10 million for women and children around the world. The imagery mostly focuses on highlighting solutions to complex problems developing communities are facing, including climate change, economic empowerment, energy infrastructure, education, health and access to healthy food and clean water.

“A lot of marketing materials that are created for nonprofits are talking heads speaking about numbers,” Griffiths says. “With everything we create, the women tell their own stories. So, you see it. You see it in their eyes. You see them. You see their spine straight and you see empowerment before your eyes. You emotionally connect with a person rather than a bar graph.”

Beyond the Lens

On top of traveling around the world, taking photos for multiple projects and starting a nonprofit, Griffiths is also a mother of two, a son and daughter, and a grandmother of three. Throughout her career, she would often bring her children along on her trips, giving them the global education of a lifetime.

“It was important to me that the teachers knew that I wasn’t disrespecting their work at all, but our family’s reality was a little bit different than most,” Griffiths reflects. When traveling, she ensured the children kept up with their classmates’ studies, while expanding their lessons too. “I always had them come back and do some kind of presentation to the class from where they were,” Griffiths says.

But how does a mother of two on a work assignment find the time to balance it all, as well as keep her family safe? “We always had a babysitter that traveled with us so that I could work,” Griffiths says. “We didn’t stay in hotels. We stayed in places that had neighborhoods that were kid-friendly. I would search for apartments for rent—once we lived on a kibbutz—or beach houses or anything that was in a neighborhood so they could run out the door and be with other children. It worked really well.”

In 2008, Griffiths released her photo memoir, A Camera, Two Kids and a Camel: My Journey in Photographs, which focused on the work-family balance that many mothers aim to create in their own lives.

Even with her current hectic schedule, Griffiths makes sure to find time for her family. “My joy comes from time with my family,” she says. “My son’s a filmmaker, so there are times when we can do assignments together, which is lovely. Each of my kids has done work for Ripple. My daughter’s a web designer. My son’s a terrific writer. But they also don’t want to just work for their mom. Like any healthy person their age, they want to forge their own careers. They’re doing that, which is great. But we’re really close.”

Griffiths’ other published book, Simply Beautiful Photographs, also focuses on featuring the images she’s taken throughout the decades. Griffiths currently speaks on behalf of National Geographic, as part of its Speakers Bureau, consisting of top National Geographic photographers, explorers and scientists. Griffiths’ talks touch upon places she’s visited and past projects, as well as how to connect with other people.

“The thing that has moved me so much is the human connection that happens just from sincerity,” Griffiths says. “I’m just a strange Caucasian lady who dropped into their world with a camera, and I’m treated with incredible generosity. Ripple Effect Images is my way of giving back to all the women who fed me, made me laugh, who gave me sisterhood.”

This post originally appeared in our May 2020 print issue. For more profiles on notable Northern Virginians, subscribe to our newsletters.