Ah, those lazy days of summer. Whether you’ve been in real life or have only seen it in the movies, summer camp looms large in the collective American psyche. Swimming, sunning, laughing, loving. The images of summer camp all seem to conjure up a hazy, halcyon coming-of-age, warm-and-fuzzy feeling (unless, of course, you spent your time in the infirmary with poison ivy). We asked four local writers to tell us what summer camp really meant for those formative years—whether as the camp attendee or a parent letting go. Read on to see if you recognize your own summers past in these essays.

What We Really Learned

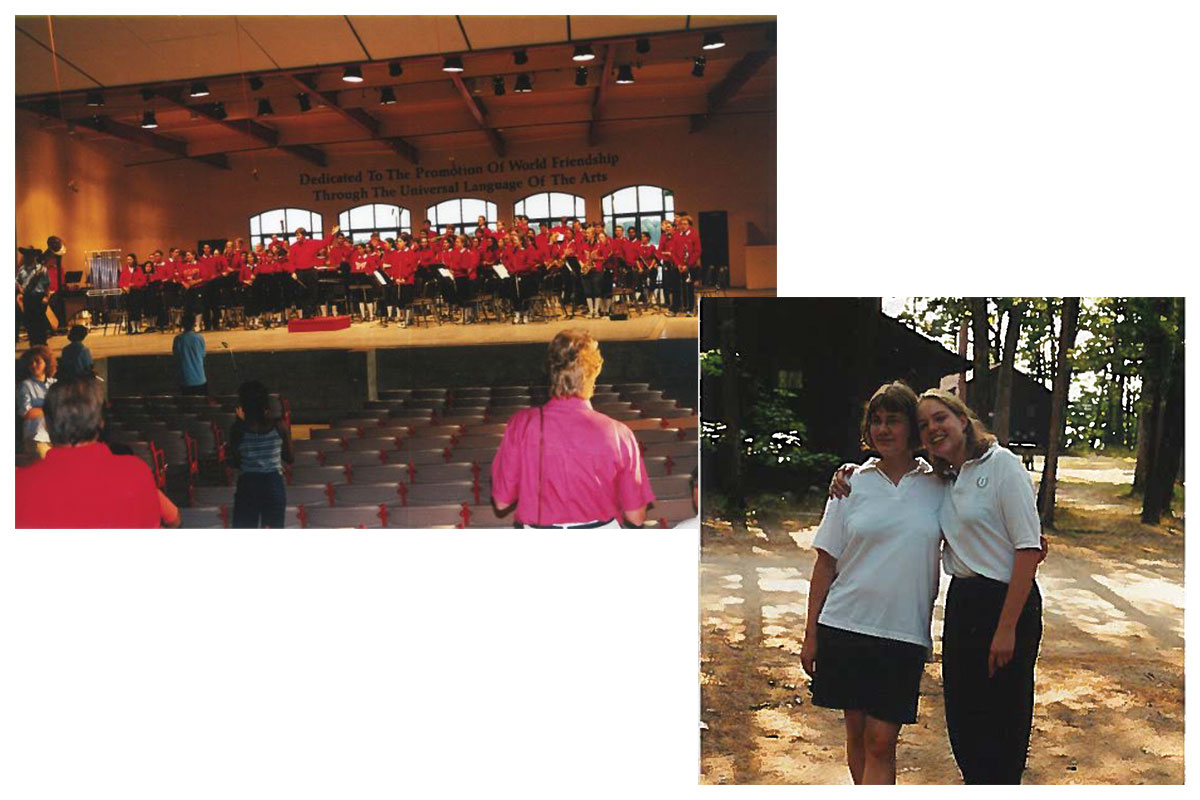

Sending my daughter off to band camp was a lesson in letting go.

By Sally Toner

It’s only 10 a.m. and already in the high 80s. I’m working the forms table for the last time. The uniform mom working beside me is glancing approvingly at how I’ve sorted. I am a band camp check-in expert. Finally, after four years at this, I have arrived.

So has a common issue the first week of band camp. Another band mom who doubles as our camp nurse comes from the turf to the table, shaking her head.

“Another one down,” she says, grabbing two water bottles and indicating that a tuba player or percussionist is threatening to pass out.

Between the sweltering Virginia heat, the polyester uniforms and high school kids who don’t think about dehydration, that first time on the field at band camp can result in more than a few near-fainting episodes.

It’s one of the many reasons I was grateful my daughter played the piccolo—an instrument you don’t have to wear.

This year, my daughter, Aimee, was attending band camp for the last time, a senior in high school with college on the horizon. I was also an expert this time around. And I had wisdom to pass on to the newer parents, those just getting initiated into the ways of band camp.

As a teacher of 27 years, I’m an experienced educator. I don’t teach music, but I can appreciate an engaging lesson plan. My daughter’s band director shows parents, including myself, the hard work our sons and daughters put in during those three weeks in August.

Step One: Make sure parents and students are wearing matching, themed show shirts.

Step Two: Line parents and students up, side by side, on the field, in formation. Ask students to pass their instruments to said parents.

Step Three: From up in the press box, call out set commands and watch trombones dropped, piccolos pointed in the wrong direction and hilarity ensue.

Parents feel clumsy, but it gives them a window into what their children are learning, the teamwork it takes to make a halftime show sing.

The first time my daughter, Aimee, wore a uniform, it swallowed her less-than-5-foot frame. She was only in the seventh grade preparing for the Herndon High School homecoming parade. Fairfax County Public Schools introduces marching band to its elementary and middle school students via a time-honored tradition of pairing symphonic band members with high school counterparts to march on the field and play “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Aimee was still so small, the shako fell over her eyes and we had to switch out the gloves so she could play. But she was ready. I’d be lying though, if I said that her parents were.

“What the hell is a shako?” my husband asked when she was looking for it. (A shako, for the uninitiated, is the marching band hat worn with the aforementioned polyester uniform.) Aimee smiled and pointed to the plumed hat sitting on end of the living room sectional. It was one of those smiles that said, “I know something you don’t. There is finally something I can teach you.”

For me, my daughter’s interest in music was not a totally unfamiliar experience. I was a music minor, but I was not a band kid. I moved in the eighth grade (too late to earn a spot on the high school band), so though I coveted my clarinet-playing best friend’s position in the halftime show, I was relegated to playing piano and guitar in my living room. After a failed attempt at teaching my own child piano, I insisted that her next instrument be one I knew absolutely nothing about. She chose the flute, and I refused to attend lessons with her for the first year that she took them. I wanted music, if she chose to pursue it, to be something that belonged to her.

Band camp was a chance for her to find an activity, a tribe, completely unfamiliar to me. At first, it was a little unnerving, picking her and her friends up freshman year speaking the foreign language of drill competitions, drum majors, section leaders, lyres.

Shakos.

When she became music librarian as a sophomore, there wasn’t much I could offer in the way of suggestions for cataloguing. I dimly remembered how to read an orchestral score, but all I could do was listen and provide some basic rhythm suggestions when she competed for a solo the next year. We teach our children so many things—how to tie their shoes, how to read, how to drive—in the ongoing quest to ready them for adulthood. We extol the qualities of leadership, but nothing compares to having to do it for real, as music section leader, with a line of sweaty high schoolers when you’re only 16. It’s trial by fire—with literal heat radiating from 100-degree asphalt.

I didn’t choose to pursue music for a living. My daughter however, has, and I saw the legacy of those August band camp sessions at a concert of hers last month. She is a recent college graduate, and the concert was a student-run ensemble she was conducting for the last time. It was a beautiful performance. Aimee conducted with confidence—a quality that as parents, we hope to see in our grown children.

Afterward, I watched Aimee and her friends. I watched them, taller, with sharper features and no braces, now wearing long black dresses and tuxes instead of uncomfortable uniforms and shakos. I watched them as they wrapped their arms around each other, on three hours of sleep, laughing like loons after doing a damn fine job together. As a recent college grad, Aimee’s music career is just beginning. But, as I watched her, it was clear that those years spent sweating at band camp taught her so much more than how to march piccolo.

Sally Toner has lived, taught and written in the Northern Virginia area for 25 years. Almost four years after her daughter’s graduation, she still has a Pride of Herndon Band magnet on her car. Once a band mom, always a band mom.

Saving Grace

A strict, religious upbringing colored my worldview. And then I went to Bible camp.

By Mathina Calliope

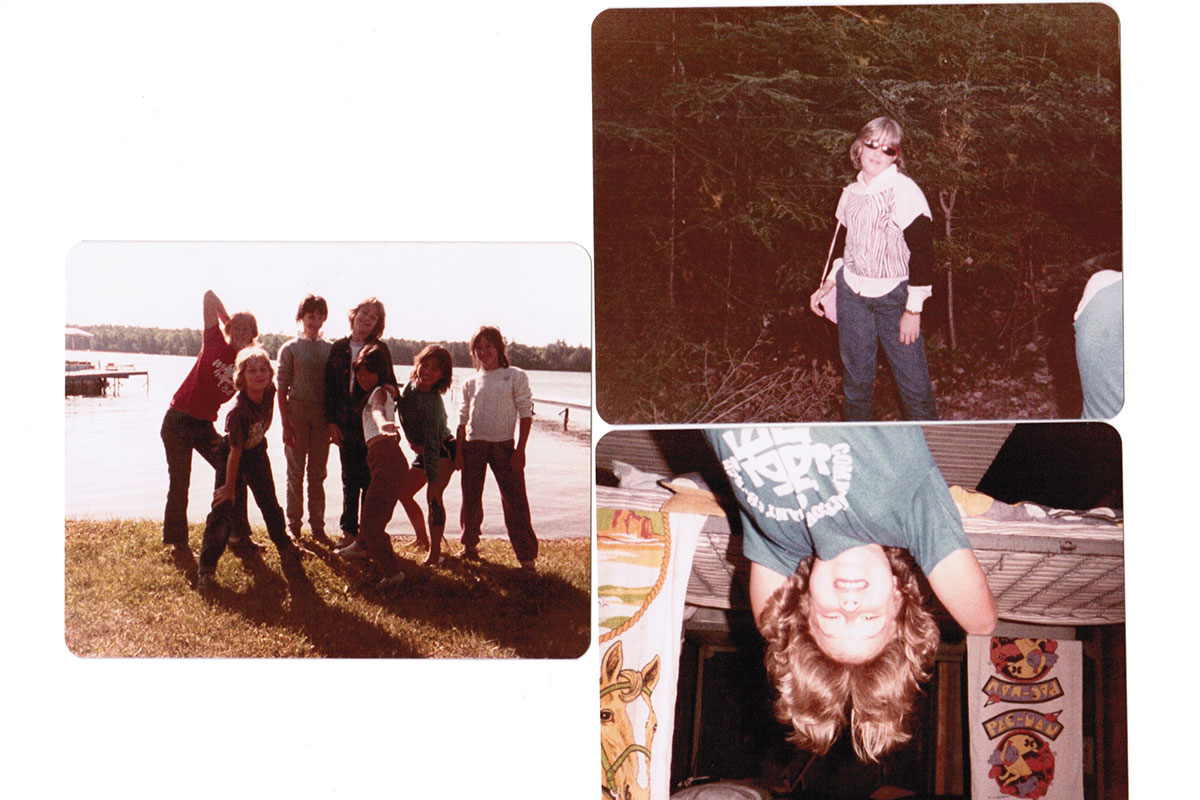

It was flashlights flicking over the path to the cabins after singing folk songs around the campfire. It was staying up late. It was a no-rules, slumber-party feeling. Candy in bed, whispers with my cousin Su-Su. Cicadas whirring out in the woods. Crushing on the counselors. My old, red, cotton sleeping bag clinging to the faint scent of home. Scratching at mosquito bites, picking at scabs. Hushed wonder in the forest on an owl-seeking night hike, stepping softly on pine needles, listening for the haunting hoo-hooo.

Bible study camp was my favorite week of the year.

More importantly though, it was proof that the world was wider than what I knew at home.

In addition to the usual charms that come with overnight camp—and despite it being a religious camp—my formative years spent at summer camp provided a break from my conservative Christian parents and showed me that not all God-fearing people were exacting and authoritarian.

My parents grew up in Michigan and Illinois and, bringing along their Midwestern values and sensibilities, moved to Northern Virginia just before I was born. Staying true to their religious roots, they found an outpost of a church from back home; refrained from drinking, drugs and R-rated movies; and voted for Ronald Reagan. My grandparents, who lived in Michigan near my Bible study camp, were even more fundamentalist, prohibiting dancing and other simple pleasures. Being raised this way in the liberal-intellectual suburbs of DC, I didn’t often fit in with my secular peers.

My mother emphasized intellect over fashion. Clothes for her were functional, and although she allowed me to choose what I thought was stylish, I chose wrong. My professor mother also had no time to get me ready for school, so rather than “deal with” my fine, prone-to-tangle hair, she had a friend chop it short in a home haircut when I was in fourth grade. At school the next day, when I tried to sit in my usual spot, a popular girl shook her head and pointed across the cafeteria. “The boys’ table is over there.”

It was in that context that I attended Covenant Point Bible Camp in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula in the 1980s. The camp proved to be an escape from both my seemingly more sophisticated peers in NoVA and my conservative Christian family.

At camp, although I was just as awkward and social skills-deficient (A misguided attempt to charm my cabinmates by affecting a Yoda-like, deep-throated, burpy voice at the height of Star Wars-mania secured me my usual bottom-of-the-totem-pole standing and earned me a rain-soaked pillow.), I had the friendship of Su-Su, who loved me despite my awkwardness, and the loving kindness of the cool counselors, who practiced a warm, accepting Christianity. At the fire each night, we sang tearjerker songs and leaned into each other, swaying and swelling with love. All around us was God’s natural beauty, and this felt like love to me too. I relished the embrace of woodland loveliness.

So while camp was a more nurturing environment than school back home, it was also the mirror I needed to recognize that my childhood awkwardness went with me no matter where I was. It wasn’t that the kids back home were mean (or it wasn’t only that); I simply hadn’t learned the social mores of 1980s tweendom, and thus often felt dorky and inappropriate, oblivious. Learning this lesson in the safe space of camp was hard, but maybe not as hard and hopeless as it would have been back home. I didn’t magically start to understand social dynamics, but I took heart from the fact that a community could exist that would love me anyway.

Before Bible camp, I believed what my parents said without question. Their authority simply was; it derived from the natural order of things. All my parents’ ideas about how to live—from drinking Pepsi only on Sundays to getting straight As (not that I did) to listening to country music instead of rock—flowed from the Bible, if only because the Bible said to honor our parents and these were our parents’ predilections.

Yes, camp reinforced this, but only to a point. At camp, we sang folksy, guitar-accompanied songs, not hymns, and we did it wearing shorts and T-shirts, not uncomfortable dresses, tights and hard-soled, black-patent-leather shoes. From this, I understood that dressing up and singing slow, organ-accompanied music was not the only way to worship God. All the other rules were looser too. Outside of camp, I believed such relaxedness was not just inadvisable but wrong—not in God’s will. But a camp I attended in high school was so relaxed it held a dance at the end of the week. The camp leaders seemed more like Jesus to me than any adult in my family though, so I figured it must be all right.

Although as an adult I’m an atheist-leaning agnostic, my time at Bible camp instilled in me values such as accepting others, singing together as a way to draw closer and appreciating the natural majesty of the forest.

The summer camp trope features homesick, crying kids, especially for the first night or two. But camp was always my happiest week of the year. I loved it with an undiluted ecstasy.

Mathina Calliope is a writer, editor, teacher and writing coach living in Arlington. Her essays and fiction have appeared in Longreads, Cagibi, The Washington Post Magazine, Outside, Off Assignment, The Wall Street Journal and elsewhere. She eventually evolved into a mostly socially well-adjusted adult.

Summer Magic

For one shining summer, I was the popular girl.

By Susan Anspach

My final summer at camp, I worked as a counselor. A terrible one. We were the sloppiest cabin, and slept through “Reveille” (It was that kind of camp, with lots of lakes and knee socks and archery.) more than once. I was 19 years old, and my campers were 14. None of them listened to me. Also, my heart wasn’t in it, because where I really wanted to be was three years back in time, when I was a camper at the same place, with my first camp boyfriend and all my best camp friends.

It’s tacky to brag about this sort of thing, but I had the world’s cutest camp boyfriend. Like, if there were a trophy for world’s cutest, this guy’s face would have been on the trophy. It was an arts camp, and he played the trombone, if that gives you an idea. He was super cool and well-liked and carried the type of swagger that maybe isn’t particularly rare for male 17-year-olds, but less common amongst male 17-year-old band geeks. I dated him for one half of a summer, 20 years ago.

I dated him. Me.

I’m telling you this because it was in no way conceivable that the same thing—a popular boy showing the faintest glimmer of interest—would have happened back home. But everything at camp was like that! At least it seemed that way to me. While life back in Manassas was humming along as it usually did, here in rural Michigan, social opportunities (read: boyfriends) were mine for the taking! Here was a real-time, alternate reality populated with peers who laughed at my jokes, who cared about my opinions on hair and knee-sock height.

Plus, as a bonus, my friends at home actually seemed to be missing me. I got letters from people whom I would have never expected them from. Little stacks of mail and care packages arrived on my pillow and in Bizarro Land—i.e., camp—nobody else did a double take. It didn’t not make sense to them that a boy back home was writing me too. (This made zero sense.)

To give you an idea about the life where I’d come from, I wasn’t the type of person who sat alone in the school cafeteria, drafting lonely poems. I was someone who applied to spend her summer at a rural arts camp and celebrated the acceptance letter with her dog.

So I loved camp, where I was popular and funny and respected by my cabinmates. Obviously I loved it. And if the glory of my second summer there didn’t quite match that of my first, by that point I was too blindly loyal to the idea of camp, to ever consider turning my back on it. Besides, after 10 months of my having gone on about it, I’m sure my rest-of-the-year friends were glad to see the backside of me for another summer.

The summer after that was the one before college, and the rest of life ground to a halt getting ready. By the following year, the call of the knee socks was tugging at me again, hard. I got a job as a camp counselor, which, if you’re wondering, is not a hard thing to do.

In fairness, that last summer at camp wasn’t all bad. It just wasn’t camp—or what I thought of when I thought of camp. It was office work, and medication to supervise. It was lifeguarding and paperwork and curfew enforcement. It was three cases of head lice, and the middle-school-girl hysteria accompanying head lice.

It was bewilderment. Why wasn’t I having the time of my life? Why didn’t my girls love me the way I had loved my old counselor? For one thing, because you can’t force that sort of thing, and for another, because it was summer 2003, not 2000—which, in a bitter twist, was what made summer 2000 shine all the brighter in hindsight: as a tangled-up, fleeting, fresh surge of people all pushed together, for that singular time. For first love, or first head lice. You don’t show up at camp thinking about it on such existential terms—but maybe you leave on the last day doing it a little.

Summer 2003 didn’t belong to me in the way the summer three years before did, except that it did go to show me how good it really had been. I knew it better now for not having hold of it, and learned to carry it even more tightly inside me: that I was good in that moment, that the things I felt and the people I felt them about were good, and that camp was good. That it really, really was.

Susan Anspach is a product of Northern Virginia’s schools, swim teams and cultural mores. She still plays that one mix CD from summer camp 2000.

This post originally appeared in our March 2020 print issue. For more heartfelt stories from NoVA residents, subscribe to our weekly newsletters.