On what was described as an unbearably hot night on July 17, 1932, farmhand Shedrick Thompson burst into the bedroom of Henry and Mamie Baxley as they slept and did the unthinkable.

Thompson clubbed Henry with a stick of firewood, breaking his arm and knocking him unconscious. He dragged Mamie from the bed—their 2-year-old son was sleeping in the next bedroom—and forced her into the humid moonligt fields of the Baxley’s rural Fauquier County farm. Eventually Thompson knocked Mamie unconscious,

took the rings from her fingers and left her for dead in the pasture.

Mamie would later say that Thompson raped her.

The attack spawned the largest manhunt in the region’s history as hundreds of citizens, including members of the Ku Klux Klan, joined law enforcement officials in searching the heavily wooded hills of Fauquier County. The search went on for weeks. Had any of the enraged searchers found Thompson, a black man who, with his wife, were 15-year employees of the popular and well-respected white Baxleys, they most certainly would have strung him up on the spot. In 1932 Virginia, Mamie’s words of rape were his death sentence.

The case of Shedrick Thompson and his sudden act of violence is recounted in longtime Virginia journalist Jim Hall’s 2016 brisk book, The Last Lynching in Northern Virginia: Seeking Truth at Rattlesnake Mountain, a deeply researched history of the saga that captures not only the facts of the case but also casts them in the Depression-era milieu of rural Northern Virginia.

But good luck finding the book for sale in Fauquier County. Hall and his publisher had such difficulty locating willing retailers that The Washington Post’s media watchdog, Margaret Sullivan, wrote a column about the reluctance to carry a book about what Hall calls “the open wound” in the tradition-bound county. More than 86 years later, the attack on the Baxleys remains sensitive for some.

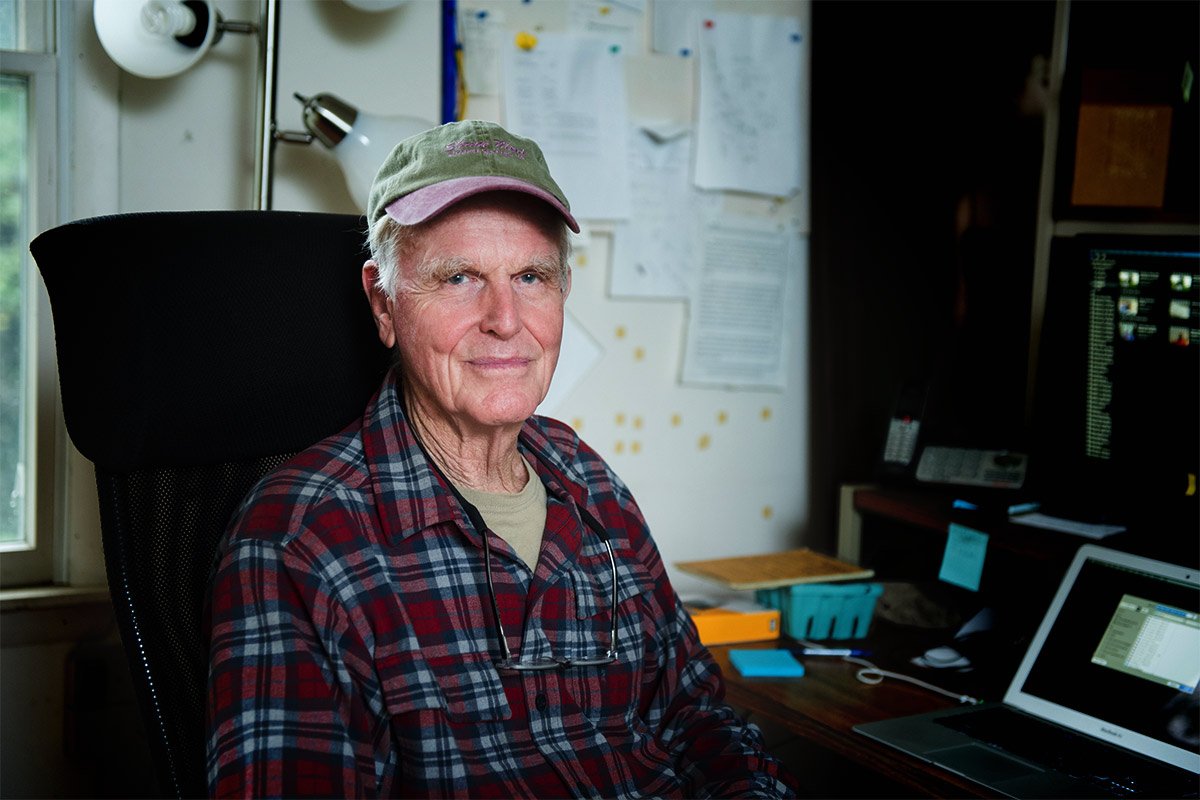

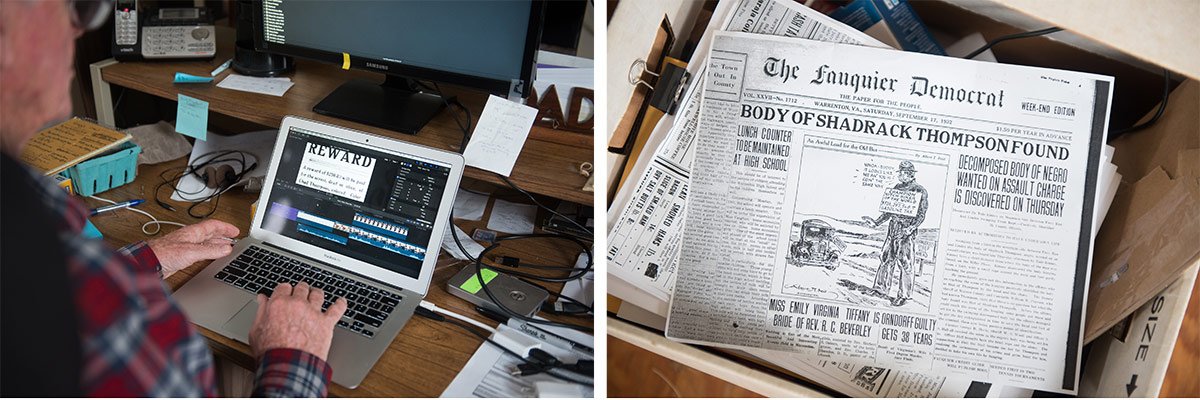

And now Tom Davenport, a longtime county resident, entertainment streaming pioneer, farmer and filmmaker, has finished a documentary retelling the Thompson-Baxley tragedy. The Other Side of Eden: Stories of a Virginia Lynching—the Baxley estate was called Edenhurst—is a 57-minute film with historic footage and contemporary interviews of those who were alive at the time of the attack.

But good luck seeing it. Someone sued to block the distribution and screening of the film.

And unlike Hall’s book, which pushes on a lingering social bruise, Davenport’s movie explores a possible reason why Thompson did what he did, and it isn’t pretty.

Even less pretty is what happened to Thompson when they caught him.

It’s a warm, late July afternoon in Delaplane, exactly 86 years and 15 miles away from the Thompson-Baxley tragedy. The picnicking customers who have made the drive from the city to the Hollin Farms pick-your-own farm-to-table operation have filled their plastic bags with the season’s bounty and packed the kids into the car for the ride home, leaving Davenport and a visitor alone on the expansive farm lands.

A stroll through the gardens gathering homegrown goodness is wonderfully calming, and the occasional endorphin rush of finding a particularly large tomato or peach is a small thrill. One begins to understand the appeal of the pick-your-own concept. Davenport’s son, Matthew, took over the farm operations years ago and began applying his agricultural engineering training to farming. As Davenport gives a tour of the property he points out his son’s innovations as a successful first-time farmer.

With Matthew at the helm of the family business, Davenport had more time to pursue his passion for filmmaking, something he’s been doing for six decades.

Davenport is tall and rangy, and moves with an ease that belies his 79-years-of-age. He and his wife of 48 years, Mimi, live on property adjacent to the working farm. The pre-Civil War house was remodeled with leftover building materials from when Davenport’s father, Robert, was developing the Alexandria neighborhood of Hollin Hills in Hybla Valley in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The neighborhood was, at the time, architecturally innovative and is now a historic district. The farm is named for the development.

Davenport lived in nearby Tauxemont—also a Northern Virginia historic district—and moved with his family when he was 11 to Delaplane, where his father bought what Davenport calls “a derelict farm” for $50 an acre.

After attending high school in Alexandria—he went to boarding school at Episcopal High because he wanted to play football with a successful program—he went to Yale University where he majored in English, “but I was a lackluster student,” he admits. “I enjoyed it immensely, but because my classmates were so interesting. It was very exciting intellectually.”

In his senior year he applied for a program that sent him to China to teach in Hong Kong for two years. It was his first overseas trip, and it broadened his world view. When his two years were over, Davenport landed a scholarship to attend the then new East-West Center at the University of Hawaii. The center, still in operation, makes its mission of promoting relations among the U.S., Asia and the Pacific nations with cooperative study.

In his spare time he experimented with photography under the tutelage of a Yale professor who happened to be in Hawaii on sabbatical. “It was the one time in my life I felt I had found a direction and didn’t wonder what I was going to do with myself,” says Davenport. “I was determined to make photography and filmmaking my career.”

His photos got the attention of National Geographic, which signed him to a contract to make images of the Taiwan region. “They gave me all the film and processing I needed,” he said. The thousands of photos he made during his term with National Geographic were recently donated to the University of California-Berkeley where they will be archived. Some will be assembled for exhibitions.

Once his Asia excursions ended, Davenport went to New York to break into filmmaking, falling in with established documentarians, among them Robert J. Flaherty’s (Louisiana Story) cinematographer Richard Leacock and director D.A. Pennebaker (Bob Dylan: Don’t Look Back). Davenport made his first independent film in 1969, a documentary on tai chi.

Around 1970, his father made him a life-changing deal: “My father sold me the farm at cost,” he says. This was huge, he says “because I had no mortgage, that was a big factor in me becoming a filmmaker.”

With funding from grants by the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities and other funding councils, he made narrator-less short documentaries about rural culture in transition. It Ain’t City Music (1973) depicts the vanishing traditions of old-time country music set against the National Country Music Contest at Lake Whippoorwill in Warrenton; Born for Hard Luck (1976) profiles Arthur “Peg Leg Sam” Jackson, a one-legged South Carolina bluesman; and The Shakers (1974) examines the traditions and means of survival of the longtime communal religious sect.

At the same time, Davenport began to remake classic folk tales from the Brothers Grimm, recasting them in rural Appalachia. The 16mm, live-action series began with Hansel and Gretel (1977) getting lost in the woods of Fauquier, to Willa: An American Snow White (1998), shot in Delaplane and at Leesburg’s Morven Park’s mansion.

Willa, a period piece set in 1915 and punctuated with special effects, rudimentary as they are, was a stab at a larger budgeted film with a professional cast—Broadway-veteran John Neville-Andrews, Floyd King (on stage this year in Camelot) and popular mime and clown Mark Jaster, among others. The average budget of his other films was about $20,000, but Willa cost about $300,000 and a piece of Hollin Farms. His film’s budgets, Davenport says, caused Mimi, his longtime co-producer, costumer and set designer, to put the brakes on the filmmaking until it could prove profitable.

As for documentaries, a terrible thing happened in 1990: Ken Burns unleashed The Civil War on the Public Broadcasting Service. The nine-episode, cinematically rich, painstakingly researched program drew massive amounts of eyeballs to PBS’s often-neglected stations. Overnight, local public television outlets, and the mighty PBS itself, wanted major network viewership numbers and not the kind of audience drawn to the low-budget, rough-hewn independent films Davenport and his cohorts were making.

“Then all they wanted was Ken Burns films,” Davenport laments. “PBS didn’t want little films, they wanted series. And the funding dried up. They wanted big projects about national events, they didn’t want little quirky films about an Appalachian storyteller. They didn’t think that would attract a national audience.”

So where to air these short and culturally important homemade films? Davenport, it turns out, was ahead of his time.

“Remember Napster?” Davenport asks. Those of a certain age might not remember the precursor to today’s popular music streaming outlets.

Davenport and his wife created a streaming website for Willa where viewers could watch the films without going to a theater or turning on a television. You could watch on your computer, in those days a revolutionary idea for the most part. Davenport approached William Ferris, then head of the National Endowment for the Humanities and a folklorist himself, and suggested that someone is going to do for film what Napster is doing for music, and that he would like to do it for documentarians.

“Nobody was talking about streaming video,” Davenport says. “I told him that all these folklore films that people have been making for generations that represent their times—independent films sitting in closets—why don’t we do something where people can find these films?”

With the help of technology savant Steve Knoblock in Arlington, Davenport created Folkstreams.net. Davenport says it’s the longest running video streaming site. Had Davenport taken his idea a step further, he might have invented YouTube and we would be having this conversation in a chateau somewhere.

“YouTube is a rival system, yes,” Davenport says. “But we’re curated by humans, and that’s a big difference. We utilize the expertise of folklorists and filmmakers and we develop contextual things around the films. It’s much more complicated and much more niche-like. We also don’t have a profit motive, which is the Achilles heel of YouTube.”

Davenport acknowledges the encouragement and contributions of North Carolina folklorists Dan and Beverly Patterson, former film reviewers for the Journal of American Folklore, for bringing context and filmmakers to Folkstreams.net.

Among other things that is impressive about Davenport is that at age 79 he does the tech work himself these days. He’s had to teach himself and stay up-to-date with the mind-numbing, rapidly changing facets of compressing and uploading very large, very old movies for 20 years.

“I’ve had an interest in technology always,” he says. “Right now I’m researching blockchain and Bitcoin, the issue of something that’s going to upend the hegemony of Google.”

And this: “My next film is going to be shot on an iPhone. Why not?”

Hall did not know Davenport when he was a daily newspaper reporter. But on his last week at work at the Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star at the end of a 36-year career

as a newspaper journalist, “I got a call from Tom,” Hall says. “Tom had been interested in the case for a long time.”

Hall, whose master’s thesis studied how newspapers covered lynchings in Virginia, wound up working with Davenport for two years on the same-but-separate projects. Hall covered the story for his book as a lynching and a political coverup by Gov. Harry F. Byrd, who could ill afford a lynching on his watch, and is convinced that Thompson battered the Baxleys and raped the wife. “No doubt,” he says. “I think it was what it seemed. The only mystery is, why?

“Tom had a slightly different take.”

Davenport’s reportorial breakthrough, with genealogical research by his assistant Shawn Nicholls, was when he discovered that Henry Baxley had a daughter with his previous black cook 10 years before the attack. A light-skinned girl was rumored in Fauquier’s black community to be Henry’s daughter. If Thompson had an inkling that Baxley was likely to

abuse his power and race with one cook, then why not with his own wife?

“Well, that would give Thompson a motive,” Hall says. “But it had been 10 years, I think, and that makes me a little bit less certain.”

“Early on, I resisted the direction that Shawn’s curiosity took and defended the white establishment of Fauquier, which held Henry Baxley Sr. in the highest regard,” Davenport says. “But her persistence and research allowed the film to take an interesting and ultimately healing direction as it acknowledges the sexual advantages of whites over blacks in the shadow of slavery.”

One of the local people who briefly appear in the film is a woman in her 90s. She doesn’t say anything damning, but someone in her well-heeled family decided they did not want her in Davenport’s movie after all—apparently, the wound is still an open one for them. Incensed by the impudence, Davenport refused to remove the footage. Soon, a cease-and-desist letter from a white-shoe Washington, D.C., law firm threatened significant penury punishment.

Hall, who has seen it all as a newspaper reporter with his roots in hot type, says Davenport was nothing but courageous in the face of litigation.

“I am proud of Tom,” Hall says. “He was as strong as any newspaper editor you ever wanted to work for in standing up for himself and for what was right.”

Davenport fired back a letter that his film was not fiction, not a commercial endeavor and that freedom of speech laws reign supreme in this case. “The reply was just excellent,” Hall says. “And then there was silence from the family. They were licked and walked away.”

And now, Davenport can show, sell and stream The Other Side of Eden in any forum he likes.

Two months after Thompson’s assault on the Baxleys, and with Gov. Byrd refusing to lose face by admitting Virginia had seen an outlawed lynching, Thompson’s body was discovered by a white tenant farmer on Rattlesnake Mountain, about 4 miles from the Baxley’s house, hanging from an apple tree. Despite significant decomposition, the body was confirmed as Thompson’s. He had been dead, the death report says, “a considerable amount of time.”

The mob of 150 that descended on the scene set fire to the body before it could be examined for any evidence of a crime. The only deputy on the scene was stopped at gunpoint as he tried to put out the fire. Nothing was left of Thompson but his shoes and skull.

The death was ruled a suicide.

The Other Side of Eden: Stories of a Virginia Lynching is available at https://vimeo.com/ondemand/otherside and on Amazon Prime.