Alexandria, the early 1900s.

It’s a separate but equal world in Virginia. That was the law throughout the country since 1896. Segregation was legal. Americans were living under a virtual apartheid system.

Grade schools for African Americans in the city were segregated—and substandard. There was no high school for black kids. They had to go into D.C. to pursue higher education.

Like all cities in Virginia, the black and white populations lived apart in Alexandria: whites lived on King Street and south, blacks lived on Queen Street and north.

One of those black families was the Tuckers: father Samuel A. Tucker, Jr., born in Alexandria; wife Fannie, a farmer’s daughter and teacher from Fauquier County; sons George, Otto and Samuel W.; and daughter Elise.

Samuel Tucker, Jr., was a smart, serious guy, a jack of all trades trying out different jobs. He ran a grocery store, a restaurant; he was an insurance man, a bartender. Then he bought a building and got into the real estate business around 1924.

With him in the building he owned was a family friend and attorney, Thomas Watson. Tucker, Jr., wanted to be a lawyer, went to law school at night in D.C., but didn’t pass the bar. Tucker’s son, 10-year-old Samuel W. Tucker, would hang out in his dad’s office, read law books from Watson’s collection, listen intently to what was going on as the two men talked about business and law, even prepared court documents for Watson by the time he was 13, building a foundation to question the establishment and get involved at a young age for a life that he knew was unfair to black people.

Then, still just a boy, he got arrested in an event that changed his life and focused his future ambitions.

Every day, young Tucker took the trolley over the 14th street bridge into the district, passing the whites-only Jefferson High School in Alexandria just a few blocks from his family’s house. Then, after crossing the bridge, he would walk two-and-half miles to go to Armstrong High School. He was doing well in school, studying to be an architect.

The trolley would stop in the middle of 14th street on the way back to Alexandria, and an announcement was made: all whites come to the front, all blacks go to the back. That’s the way it was in 1927.

On this particular day, Tucker, riding with his brothers Otto and George, repositioned one of the moveable seats in the white section to face seats in the black section. A white woman objected to the incursion into the white part of the bus, but the three boys refused to turn the seat back around. When the trolley stopped in Alexandria, she found a fireman, told him about the incident, and 14-year-old Tucker and his 11-year old brother George were arrested for disorderly conduct. They were tried and convicted of the crime.

Their dad’s attorney friend, Watson, appealed the conviction and an all-white jury found them not guilty. Through that experience—young Tucker’s first-person experience of suffering the indignities of segregation and seeing how the law could be used to fight it—he had found his calling.

Fast forward a dozen years; 1939. Segregation was being challenged and quiet events were happening in the background around schools and property issues. The white establishment in Virginia was beginning to sense trouble brewing.

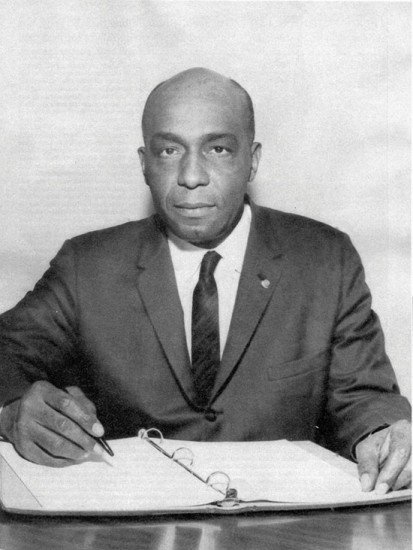

Smart African American men in the state were stepping up. Under the watchful mentoring of Watson, Tucker—a cool, composed whip-smart 26-year-old, six years out of Howard University who taught himself law and passed the bar when he was just 20—was the right guy at the right time who was destined to make a difference.

Tucker had studied law at the Library of Congress. Right across the street at the time, the Supreme Court building was being built. He would spend his later years trying landmark desegregation cases there.

He was a trained debater from his time on the debate team at Howard. He saw how words influenced actions, how people responded to a leader who stood up for what is right.

At Howard, people from India were brought in as part of speaker’s program about solidarity in the face of racism. Tucker learned about the non-violent civil disobedience acts Mahatma Gandhi invoked to help his people resist the oppression from the British.

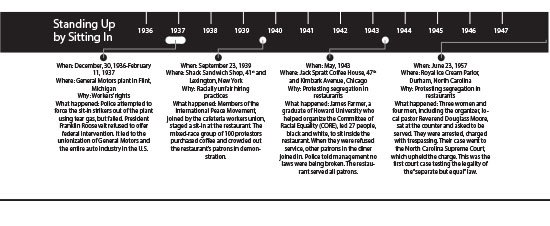

Tucker had read about the 44-day sit-in autoworkers staged in December 1936, at a General Motors plant in Flint, Michigan for better wages and working conditions that resulted in the formation of the United Auto Workers Union.

It was clear that sit-ins had become a new non-violent tool in the fight to equalize the have-nots with the haves. And there was always the Constitution that said all men are created equal. Tucker was a constitutional scholar, and he would use that document throughout his professional career to fight for the equality promised to all Americans.

In 1939, a new, whites-only library had been built in Alexandria, just a block from Tucker’s house. When a black neighbor in Alexandria tried to get a library card and was refused, Tucker saw his chance to do the right thing. He would use his officer’s training as a second lieutenant in the infantry reserves at Howard to organize and conduct an operation.

He got his brother Otto and five others to stage a protest at the Alexandria library. Each young man, properly dressed and respectful, went into the library, one by one, and asked for a library card. When they were denied, they each took a book from the stack, sat down and refused to leave. The librarian called the police.

Bobby Strange, 14, was one of the protestors assigned to be the lookout and update Tucker about what was happening. When Tucker heard the police were coming, he alerted the press who got there just as the five protestors were lead out in front of a crowd of stunned onlookers.

The boys were charged with trespassing; however, Tucker challenged it, successfully arguing that they had a right to be in the public library, and the charge was changed to disorderly conduct. At trial, Tucker got the librarian and the arresting officer to admit that the protestors were arrested only because they were black, not because they were disorderly.

The opposing counsel was Armistead Bruce, a lawyer who would share bourbon with Tucker out of sight of the general public in a social setting of mutual admiration, and would go on to be one of Tucker’s lifelong friends.

An official ruling was never made, the case ended up in limbo, and the protestors were never jailed.

A smaller, beat-up library was quickly opened for blacks to use, but Tucker wasn’t having it. In a letter to the librarian of the Alexandria library, he wrote: “I refuse and will always refuse to accept a card to be used at the library … in lieu of a card to be used at the existing library … for which I have made application. Continued delaying … in issuing to me a card … will be taken as a refusal to do so, whereupon I will feel justified in seeking the aid of court to enforce my right.”

Two years later, in March 1941, Tucker was called into action during World War II, serving in the all-black 366th Infantry Regiment as first lieutenant, later as captain. He took part in fighting in Italy in 1944, action that hardened him to the fights he was to enter into once home again in 1946.

He moved from Alexandria to Emporia to continue his law practice, the only black lawyer in the city, and married Julia Spaulding in 1947, a woman who he met 10 years earlier and kept in touch with while in the service.

By the 1950s, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909 and making headway fighting for voting and housing rights for blacks in the Supreme Court, was on the offensive fighting the separate but equal ruling for schools in the state. They recruited Tucker, along with Howard Law School graduate and future Supreme Court justice (1967) Thurgood Marshall, and one of Tucker’s law school colleagues Oliver Hill. Marshall led the team of lawyers that won the landmark Brown v. Board of Education cases in 1954, proving that it was unconstitutional for whites and blacks to have separate schools, ruling that school boards must desegregate schools.

The work with the NAACP and its lawyers began a long law career for Tucker, who argued discrimination cases in the state for years, becoming a key attorney in the leading law firm handling desegregation cases in Virginia in 1961, the Tucker and Marsh law office in Richmond.

Partner Henry Marsh III, from Richmond, had been the president of the NAACP chapter in high school and was a recent law school grad back from a two-year stint with the Army. Oliver Hill joined in 1965. These three strong, powerful connected attorneys at the Hill, Tucker and Marsh law firm were perfectly aligned for the fight for equal rights that many believe peaked in the late ’60s and early ’70s but still goes on today.

Today Marsh—serving as a Virginia senator since 1992, who also served as the first black mayor of Richmond in 1977—is a well-known civil rights lawyer and politician who handled over 50 school desegregation cases throughout his career. His interest in civil rights has been around since a very early age: “I used to walk five miles to school, first through fifth grade. And yellow buses taking white children to schools would pass me by. I used to ask where those buses were going, and why are those kids riding like that and I am walking?”

In college, Marsh read about the massive resistance hearing in Richmond; the state was defying the federal ruling on desegregating schools. Marsh went down and testified on behalf of the student government, the only student speaking amid 37 speakers, all mostly white. NAACP attorney Oliver Hill watched and was impressed. Hill told him to keep in touch.

In 1960, with John F. Kennedy as president, Hill was appointed housing commissioner. Hill moved to D.C., and gave up his practice. That’s when he introduced Marsh to Tucker, who was now in his 20th year of practice. “We shook hands on a partnership and we started right in on cases of desegregation in the office,” Marsh says. “I didn’t practice before, but I was thrown into the frying pan so to speak.”

Over the years, the two lawyers challenged the massive resistance laws. “We challenged the tuition grant program that put a lot of public funds into schools,” Marsh says. “We cut the spigot off. And we sued companies for all kinds of discrimination.”

When Hill rejoined the firm in the late ’60s, he became a political weapon in the fight, Marsh says. “We sued the school boards and won all the cases. I did cases with Mr. Tucker in Virginia that went to the Supreme Court. We defended teachers and principals; we handled a lot of cases. Mr. Tucker was a major force and I was just a sidekick, so to speak.”

Tucker taught him everything, Marsh says. “He taught me how to practice law. He taught me how to fight for civil rights. He taught me how to litigate and be committed to the struggle. Neither one of us was concerned about the money. We were just in the fight.”

Tucker’s Supreme Court case in 1968, Green v. New Kent County, a landmark case that helped speed up desegregation in the state, was tried before the Supreme Court where Marshall, the first black Supreme Court justice, presided. Tucker won a unanimous decision.

When Tucker moved to Richmond to join the law firm, he left his brother Otto to run his law practice in Alexandria along with Melvin Miller, who came to Alexandria in 1958. Miller, another Howard Law School graduate, was interested in civil rights cases and championed the cause of fair housing practices throughout his career in Alexandria.

“Otto and I handled the local stuff until it got to where it would go to the appeals court. Then [Tucker] would take it from there,” Miller says. Tucker was just “sharp as a tack. Just talking to him was quite an amazing thing for me as a lawyer, particularly on the Constitution issues,” he says. “[Tucker] was really very good, and had such a grasp of all of that.”

It was Tucker’s deep understanding of the Constitution, and how he used that in a thoughtful and direct way, that became the foundation for his search for justice for blacks in the late ’50’s and ’60’s. “It wasn’t that the legislators of Virginia didn’t know that all men should have these rights,” Miller says. “It was just that they didn’t want to do it.”

One of the first lunch counter sit-ins at that time in the area was in Arlington, which began to affect lunch counters in Alexandria. The mayor of Alexandria appointed a biracial committee to come up with recommendations on what should be done. Miller was a committee member: “Some kids from Howard University called over to Otto’s office and said they were going to stage a sit-in in Northern Virginia, and thought Alexandria was the ideal place to do it because there would be more exposure to the event.”

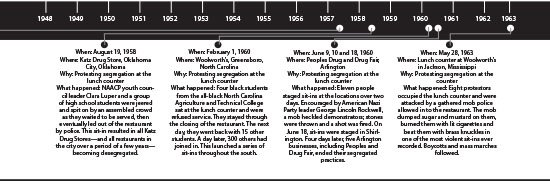

Miller recommended they do it near Alexandria, believing Alexandria would cave in because they could see what was coming. That became the sit-in at the Drug Fair in the Cherrydale community in Arlington on June 10, 1960.

The next day, the committee drafted a statement which resulted in lunch counters in a few of the chain restaurants in Alexandria opening for blacks. Others followed in 1961.

Throughout the careers of these men, all faced personal challenges about what they were trying to accomplish. Tucker was charged by the Virginia State Bar with unprofessional conduct. They tried to have him disbarred because of the work he was doing on desegregation. That didn’t happen.

Miller says the 1939 Alexandria library sit-in was a precursor to things that happened all over the south. “In order to do things like that, there has to be some organization and discipline behind it,” Miller says. “And you can’t always wait for a lot of people to do it. You can’t expect everybody to go out and get on the line and maybe get arrested. It just doesn’t happen.”

But if you are organized and disciplined—if you are right—the pressure will create the downfall of discrimination, Miller says. “You just put enough pressure and shine enough light on it, and you would find that the power structure would then decide that this isn’t worth the battle.”

So what are the lasting effects of lessons learned from the 1939 sit-in? “The only problem now is that racism is a little more subtle,” Miller says. “It was very easy to fight that ‘I couldn’t use that library’ or ‘I couldn’t eat in that restaurant’ or ‘I couldn’t sit down at that lunch counter’,” he says. “Those kinds of issues, in my mind, were easy battles.”

Racism is more disguised now, he says. “Whenever we try to do something now in the low income housing, particularly if we do it in a neighborhood that has either predominantly white or large numbers of whites in it, they fight it not because they are African American or Hispanics but because of parking or something like that,” Miller says.

Marsh says Tucker literally gave his life for the struggle for civil rights. “He was not well known but he was the genius behind the fight. Because without his interest, the outcome of the movement might have been different.”

He was way ahead of his time, Marsh says, organizing the sit-in long before students did sit-ins in the ‘50s and ‘60s. “He was a true pioneer in the civil rights movement.”

(August 2014)