In the annals of international espionage, the ladies underwear counter at the old Lansburgh department store on Seventh Street in D.C. may not be the most important location. But it is perhaps one of the most awkward.

There, one day during World War II, a group of German scientists showed up with a few embarrassed Americans. The Germans were conspicuous because they were wearing leather jackets and traditional Tyrolean felt caps, which made them look like they walked straight out of a beer advertisement into the Jewish-owned department store.

Even more conspicuous was what happened when the woman behind the counter asked what size panties they were interested in seeing. That’s when one of the Germans pulled a slide rule out of his pocket and began calculating the difference between centimeters and inches. After a little quick math, the Germans told the woman what sizes they were interested in seeing.

“But no panties with long legs and made of wool,” one of the Germans said, “because the winter is going to be hard.”

The woman behind the counter that day simply shrugged and went on about her business, handing over panties to the strange group of German men. Then the group moved over to the brassiere counter. There they had the same issue. The woman behind the counter wanted to know what size they wanted. Once again the slide rule came out and a few quick calculations transpired.

“I mean you can’t just order brassieres for God’s sake,” recalled Arno Mayer, one of the blushing Americans, in an interview with the National Park Service. “It was an unreal scene.”

Unbeknownst to the women behind the underwear counter at Lansburgh’s that day, these were not just vacationing Germans. They were prisoners of war detained at a top-secret camp in Fairfax County, an interrogation camp the Army set up for some of the most important scientists and German officers captured during the war. The central organizing principle behind the camp was to show the Germans a good time, take them out to lunch in Alexandria and let them head into Washington to buy gifts for their wives back home in Germany. This particular day the Americans came perilously close to jeopardizing the mission.

“Just as the woman came out with the brassiere, the military police arrived and arrested the whole bunch of us because somebody must have said something,” said Mayer. “Obviously, after a half hour, we were out because I had a phone number and I knew whom to call at 1142.”

That would be P.O. Box 1142, the code name of the secret Nazi interrogation center at Fort Hunt. It was also the actual mailing address. There, behind an iron fence and razor wire, 3,451 German prisoners of war were interrogated between 1942 and 1945. The facility included fake Red Cross workers designed to help persuade detainees to talk and imposter Russian agents who showed up to frighten them if they didn’t. The operation was conducted in such secrecy that even the folks in Old Town Alexandria had no idea that the windowless buses that rolled up and down Washington Street were carrying the most important Nazi scientists and officers captured during the war.

Today, the secrets of what happened behind closed doors are finally being revealed. That’s because the National Park Service, which owns the site, spent years tracking down people who were part of the secret operation and interviewing them. Those interviews are about to be released by the Park Service, posted on the internet for all to see—revealing the secrets of an operation that helped the Americans understand enemy military operations and weapons technology as well as the effect of the Allied bombing campaign.

“Fort Hunt was so secretive you weren’t supposed to say the name. You were supposed to call it P.O. Box 1142,” recalled Robert Kloss, an Ohio native who was in the Signal Corps before being stationed at Fort Hunt, in an interview with the Park Service. “We all wondered if the White House even knew what was going on at Fort Hunt because it was so secretive.”

The story of P.O. Box 1142 begins shortly before World War II, when the War Department established a secret radio monitoring station at Fort Hunt. Originally part of George Washington’s plantation estate, Fort Hunt became a military installation during the Spanish-American War. By the late 1930s, the Signal Intelligence Service installed special equipment to monitor traffic from four countries that posed the greatest perceived threat to American interests: Germany, Japan, Italy and Mexico. When the war broke out, the Army and Navy determined they would use Fort Hunt as a joint interrogation facility.

“In less than two months, Fort Hunt was transformed from a small undermanned post into a bustling facility of key strategic importance,” wrote Matthew Laird in a 2000 history titled By the River Potomac. “If a prisoner appeared to possess significant information, he was earmarked for shipment to Fort Hunt.”

The initial idea was to model the interrogation camp after the British, and the Office of Navy Intelligence even sent a naval reserve officer to London to study their methods. But military leaders concluded they would not be able to house prisoners of war at impressive country estates as the British did. Fort Hunt would have to do, which meant that the American model would have to find other ways of impressing the visitors.

“They would give them whatever they wanted just to get them to talk,” recalled Dominic Marletto, a native of Pennsylvania who was assigned to work in the kitchen at 1142 shortly after being drafted. “They’d furnish liquor. They’d get them women.”

In some ways, P.O. Box 1142 functioned as a sort of clubhouse. Prisoners played softball and enjoyed the swimming pool at nearby Fort Ward. They took trips into town to see movies, and cigarettes were plentiful. They had a dog named Rigor Mortis. Reading material was readily available, though the Germans were particular about what they liked to read. They preferred certain titles they believed to be more objective, including The New York Times, The Christian Science Monitor and Life magazine. They played poker, gin rummy and pinochle, though gambling was forbidden. Prisoners were told to refrain from speaking to other inmates in the latrine or through open windows. Most of the interrogations were conducted in a relaxed format.

“Though he was briefed on what type of information to seek, each interrogator was given the latitude to develop his own questioning style,” wrote Laird. “Some made liberal use of liquor and cigarettes to get the POWs to relax and open up while others took a more confrontational tack, pressing the prisoner on politics and the conduct of the war.”

One of the tactics employed at 1142 was a judicious use of stool pigeons, or decoy prisoners who were there to help elicit more information out of the actual detainees. The idea was to create an atmosphere where people felt comfortable talking. And the people running the show knew that meant creating a psychological environment where spilling the beans was not only acceptable but where there was social pressure to help the Americans.

“We put a stool pigeon in because this guy was knowledgeable on atomic energy or he knew the exact location of German army units,” explained John Dean, a Jewish German who was assigned to 1142 and later went on to be an ambassador to five different countries in the 1970s and 1980s. “I think the best way of getting information was when they were among themselves and talking about themselves and not [during an] interrogation.”

That’s why the complex had microphones hidden everywhere, in the interrogation rooms and in the cells. From the early morning hours to well into the night, Fort Hunt had a room full of monitors to overhear every word the prisoners uttered to the Americans or each other. It didn’t take long for the Germans to realize what was going on.

“When I jumped on the bed, the guard came right away,” said Anton Leonhard, one of the German detainees. “I was not that dumb.”

After a while, the Germans tried to use the situation to entertain themselves. Some of them performed mock interrogation sessions with each other, knowing the Americans would be listening. Others told stories in an effort to amuse themselves during the long, boring hours when they had nothing else to do. When the Germans refused to speak or decided to be unhelpful, the Americans threatened to call in the Russians. They even had one man dress up as a Russian officer and appear at Fort Hunt to spook the Germans. It was an empty threat, but the Germans didn’t know that.

“When they heard they were going to Siberia, that changed everything,” recalled John Kluge, a German immigrant who volunteered for the Army and ended up commanding a unit examining German documents. “The Germans were, including the generals, deathly afraid of the Russians because they knew and they heard that they would go to any means to get information from the prisoners. We wouldn’t do that.”

Only one prisoner tried to escape, a 35-year-old U-boat captain named Werner Henke who was captured by the Americans on Easter Sunday 1944. By the time he arrived at 1142, he was well-known to Allied intelligence because he was one of Germany’s most successful naval officers. Henke, who was described as a daredevil and a ladies’ man, had an extensive collection of American jazz records and a hot temper.

“He was impetuous, ill-disciplined, hot-headed and outgoing,” wrote his biographer, Timothy Mulligan.

But he also had a weakness. Before he arrived at Fort Hunt, Henke sunk an unarmed British transport ship called the Ceramic. British radio broadcast reports said that Henke ordered the survivors machine-gunned in the water, which led to calls for him to be tried as a war criminal. Leaders at 1142 knew all about the incident and were ready to exploit it any way they could.

“Midway through one interrogation session, a civilian (Office of Navy Intelligence) employee disguised as a Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer burst into the room and demanded Henke’s extradition to Canada,” wrote Laird. “In reality, the British had no definite plants to try the U-Boat captain; but when he learned that he would, in fact, be sent north, Henke issued that this was an automatic death sentence.”

The day before he was scheduled to leave Fort Hunt, Henke spent his exercise time in the prisoner’s yard just like he did every other day. But before his hour expired, he made a break for it, vaulting over a 10-foot fence and dashing toward a second fence. He climbed halfway up when a burst of gunfire erupted from the guard tower and killed him instantly.

“What we didn’t understand at the camp when we heard about it is where did this U-boat commander think he was going to go once he did get out?” asked Kloss.

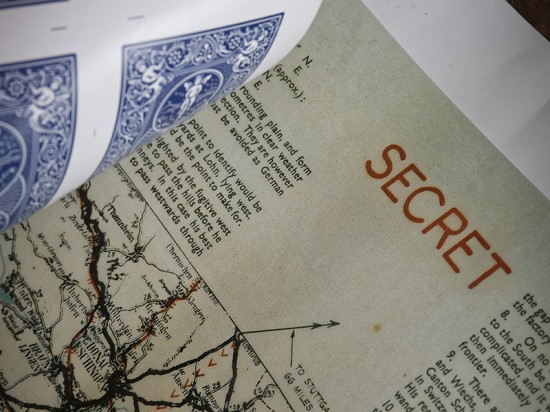

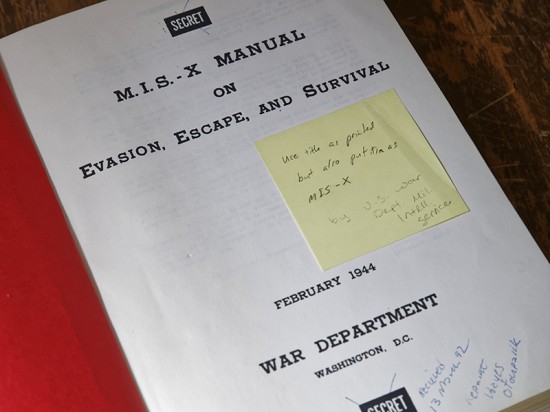

The campus at Fort Hunt included more than the interrogation of German prisoners, a program sometimes known as MIS-Y. The facility also included MIS-X, a top-secret program designed to help Americans evade and escape capture in war zones across the globe. This program included some James Bond-style gadgetry, like transmitters hidden in smoking pipes and maps hidden in playing cards. The idea was to find creative ways for Americans shot down in enemy territory to find their way to freedom.

“The old romantic spy system, like so many other things, went out with the last war,” explained the top-secret MIS-X manual. “The ace-in-the hole character, the attractive femme fatale who concentrated on seducing secrets out of high ranking officers now has a new and entirely different contract.”

Every day, duffel bags full of documents would arrive for a team of MIS-X cryptologists to examine. As many as 14 cryptologists would sit at a 22-foot table in a building known as the Creamery poring over captured German documents, maps, orders, photographs, newspapers and magazines. They also received correspondence from Americans ostensibly meant for girlfriends and wives. But the letters were actually coded messages using a numerical system in which selected words in the letter spelled out the intended message.

“There was a system of having relatives write back and forth to POWs in Germany,” Kloss recalled. “And different codes are used mostly depending on which day of the week the letter was written to determine what code would be used.”

Today, the secrets of P.O. Box 1142 are slowly emerging. Some of the documents have been declassified, and the Park Service’s series of oral histories are being transcribed. A renovation of Fort Hunt is expected to include some kind of interpretation letting people know that a top-secret facility once existed in an area that’s now known mainly to neighborhood residents as a picnic spot. Sadly, much of what happened at Fort Hunt during the war was lost forever to fire. Shortly after the war ended, an order arrived from the top brass at the Pentagon: Burn everything.

Very few documents and equipment survived. Today those remaining items are tucked away in a quiet administration building at Arlington National Cemetery.