When it comes to families, the new ‘normal’ is that there is no ‘normal.’

By Cynthia Long

Owen Gardner, 8, was in first grade when his teacher asked him to bring in baby pictures to class. Unfortunately, he didn’t have any photos from when he was an infant. In third grade, he was given an autobiographical assignment called “The Day I Was Born.” He was supposed to list the time he was born, the people who were present at his birth and other details about the momentous occasion. The assignment made the little boy’s stomach turn somersaults. He worried he would get a bad grade on the project because he couldn’t answer any of the questions.

Owen was adopted from Vietnam when he was 2 years old. His parents, Bonnie Gardner and Ray Daly of Vienna, have no information about his birth parents, no medical background and no photographs except for those they took when they met him at the orphanage.

“Suddenly, the whole adoption narrative we’d been building and adding to about how we became a family came crumbling down, and he switched to, ‘How come we don’t know any of this?’” says Gardner, 51, a web analytics professional at a D.C. educational association. “We didn’t get to choose when to weave in the details of why he was in an orphanage at an age when he could more easily grasp the concept of poverty. We had to do it right now.”

Gardner and Daly, her now-husband, decided to adopt for the same reason many people choose that path to building a family—infertility issues. Although they’d been a couple for many years, they weren’t yet married when they began the adoption process. Gardner chose Vietnam because it was one of a few countries still available to single women.

“I also chose international adoption because the timetable was more straightforward than domestic,” she says. “I was in my early forties, and I didn’t want to wait years and years for a birthmother to choose me. Or to wait years and years and never have a birthmother choose me.”

Gardner knows Owen’s teacher meant no harm, but it’s 2015, and the traditional family of the “Leave It to Beaver” years is no longer the norm. Gardner and many other adoptive parents wish more educators were a bit more enlightened when it comes to adopted kids and the different ways modern families are formed. No longer can we assume that there’s a mom, dad, house and picket fence with matching kids in the minivan.

The U.S. leads the world in adoptions both domestically and internationally. According to the U.S. Department of State, American families adopted more than 7,000 children in 2012, with the highest number of children coming from China followed by Ethiopia, Ukraine, Haiti and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Northern Virginians celebrate diversity and different ways of life, but sometimes situations outside the cookie-cutter mold can catch people off guard. Adoptive families know that intentions are, for the most part, honest and good. That’s why many, like Gardner, feel that part of their role as adoptive parents is to help educate the community and to be ambassadors of adoption.

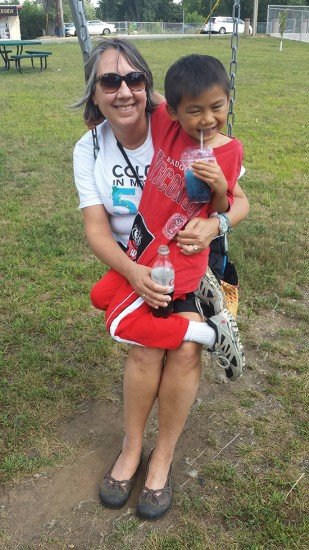

Gardner, whose short brown hair has streaks of gray, keeps her sense of humor about being an older parent. When a man mistakenly referred to her as “grandma,” she joked about socking him in the mouth and then explaining their family situation.

She’s more than happy to talk to people about adoption and help them understand both how it works and how to be more inclusive of different family structures. She spoke to Owen’s teacher and offered her some websites where she could find more inclusive lesson plans, and together they reframed Owen’s assignment to “The Day We Became a Family.” Owen listed details like who was at the airport when they landed at Dulles, like his Grandma, Pop-Pop and two cousins. They also made the presentation portion of the assignment optional because it’s important for Owen to decide how and when to share his adoption story with his peers.

“It’s his story to tell, not mine or anyone else’s,” Gardner says. “I didn’t want him to have to field difficult questions he’s not ready to answer, like why did your birth mother give you up. I didn’t want him to feel different and he really doesn’t know what he wants to share yet.”

Owen’s third-grade teacher, Larissa Roscher, was more than happy to modify the lesson. She has researched inclusive curriculum ideas and developed a new lesson where kids share their cultural background and pin their name on a world map to show where they’re from. It’s likely that most continents will contain pins.

Roscher, 29, has been a teacher for four years but has lived in Northern Virginia her whole life. She and her fiancé, a Fairfax County fireman, plan to raise their own kids here. She has watched as the demographics of the area have changed over the years and has seen how those changes are reflected in the students.

“Families now are more diverse than ever before. We have multicultural, same-sex parents, adopted children, children in foster homes, single-parent families and many blended families,” Roscher says. “Ten to 20 years ago, teachers didn’t have to think about students who might have two moms during a Mother’s Day project. They also wouldn’t have to consider that half of their class doesn’t celebrate Christmas, or that some English language learners won’t have the vocabulary to complete some assignments and that the lesson will need to be adapted for them.”

She’s also fine-tuned personal narrative assignments with the understanding that every child has a unique story.

“When planning personal narrative lessons, it’s important for students to have choice and options so they don’t ever feel pressured to share something that makes them feel uncomfortable,” Roscher says. “Sometimes I know in advance to change parts of the lesson for that student, and oftentimes I will collaborate with the student to help them feel satisfied and comfortable about their work and even the assignment.”

Figuring out what to share about adoption and when is such a common challenge for kids that the Center for Adoption Support and Education developed a program to empower kids to handle comments and questions about adoption. It’s called W.I.S.E. UP!, and it gives children and teens the power to choose if, when and how to share their adoption story with others.

“We know the world is very curious about adoption,” says CASE CEO Deborah Riley, who had been a clinical therapist for 36 years before cofounding CASE in 1998. “The W.I.S.E. UP! Program gives adoptees choices about information they decide to share or not to share.”

Nancy O’Brien, 51, of Arlington is mom to two girls from China, Maya, 15, and Talia, 12. They live in Fairlington, the sprawling, tree-lined brick townhouse condominium community near Shirlington that was built for military personnel in World War II. Both of O’Brien’s girls were adopted when they were exactly eight months and fourteen days old.

W- The “W” stands for walk away. If someone asks a tough question that an adoptee is uncomfortable answering, he or she can just walk away and not answer it.

I- The “I” stands for private. If someone asks, “Why didn’t your mother want to keep you?,” an adoptee can choose to keep some information private, like saying she was in poor health rather than saying she was an alcoholic or drug addict.

S- The “S” stands for share. Adoptees should feel empowered to share some details if they like and to feel confident that it’s OK to share their story. “They can let people know that they lived in an orphanage and that their birth parents were very poor,” says Riley. “But they don’t need to share if they were abused at the orphanage or the horrible conditions they may have endured.”

E- The “E” stands for educate. Riley and other adoption counselors want kids to be proud of their stories and of their adoption. “There are lots of negative biases about adoption,” Riley says. “We’re hoping this generation will help dispel the myths.”

“That’s their red thread connection,” says O’Brien, referring to the Chinese proverb about an invisible red thread connecting those who are destined to meet regardless of time, place or circumstance. According to the proverb, the thread may stretch or tangle, but it will never break.

O’Brien is tall and slender with short blonde hair; her daughters’ dark brown hair flows past their shoulders. Mother and daughters don’t look alike, and from their very first days as a family, O’Brien fielded all sorts of intrusive questions. “Are they yours?” “How much did they cost?” And, “Are they real sisters?”

“With that one I usually wink and say, ‘They are now,’” says O’Brien, adding that all the questions came from a place of caring or curiosity and weren’t meant to be antagonistic, even if they were awkwardly phrased.

But when her daughters began getting questions directly, O’Brien became concerned.

“They’d be asked, ‘Are you adopted?’ like it was some sort of condition,” she says. “One of my girls was a bit unsettled about my bringing cupcakes into class because then it would be obvious.”

O’Brien is a down-to-earth, affable person, confident and comfortable in her skin. She’s determined that her daughters also grow up to be self-assured and comfortable with who they are. The girls knew their adoption story from a very early age, and with the guidance of their mother, they’ve never handled questions about it in an apologetic way.

O’Brien knew that she’d adopt from the day her parents adopted her younger brother when she was 4 years old. “I just didn’t know it would be the only way I’d have kids,” she says, laughing.

She was in college at William and Mary when she heard about what was happening to female babies in China, and she made up her mind that that was where she’d adopt her daughter. She had to wait until she was 35, and on her 35th birthday, she immediately began the process. Less than a year later, she was traveling to China to bring 8-month-old Maya home. She went back two years later to adopt Talia.

When the girls began getting questions about why they didn’t have a father, O’Brien wanted to provide them with more tools to handle difficult questions with confidence and poise, so she enrolled them in CASE’s W.I.S.E. UP! program.

“There was this boy in fourth grade who was so mean,” recalls Maya, 14. “’Why don’t you have a father?’ he’d ask. ‘Did he run away? Why did your birth mother give you up?’ He went into a zone that you just don’t go into, so I’d just walk away.”

But with her friends, she’s very open and honest. She says when they meet her mom, it’s obvious that she’s adopted because they don’t look alike, and now that she’s a little older, she says wouldn’t try to hide anything from the people she’s close to anyway.

“I have a mother and a sister, and my sister and I are adopted. I don’t need to sugarcoat it,” Maya says. “I like my little family, and I don’t need to emphasize that it’s different from any other family, but I never go into very big details, like my birth mother left me on the corner of this street.”

She also gets questions about whether she and her sister are “real sisters.” She figures it’s because they are both Asian, so people assume. Maya tells them that they are related by heart and love but not by blood.

“I think that people always have a classic image of a family with a mother, father, older sister and younger brother, but my mom always taught us that families come in a bunch of different units and sizes,” Maya says. “The most important thing to me is that my mom has always been there for me and always will be.”

Robbie. Photo courtesy of Bob Insinger and Peter Larson.

Bob Ensinger, 48, and Peter Larson, 49, live in a quiet, leafy section of Falls Church. They had been together for nearly two decades and had thought about the idea of including children in their lives, but it never seemed like a real possibility. When Larson’s colleague at Habitat for Humanity of Northern Virginia told him the couple would make great foster parents, the idea suddenly appealed.

“We’d never made plans to adopt or foster, but we could see that the tides were changing for same-sex couples, so we decided to look into it and get trained,” says Larson. “Before we knew it, we were on our way.”

Their son Stephen, now 7, was 4 years old when he came into their home. He’d bounced around a few foster homes, and social services had a hard time placing him, but Ensinger and Larson knew right away that they wanted to adopt him.

“He had the same birthday as my younger brother who passed away in 2008,” says Ensinger, a communications professional for the recycling industry. “It was like someone was trying to tell us something. He loved swimming, and we had this pool that we rarely used. It just seemed like the right fit.”

The couple doesn’t get the same questions as transracially adoptive families. In fact, people have stopped one or both of them to say, “He looks like just like you!”

Stephen is Caucasian with blonde hair and blue eyes and actually does look a lot like his parents. “I had blonde hair, too” says Ensinger. “Just not so much anymore.”

Ensinger and Stephen both have blue eyes, wide smiles and ears that stand out ever so slightly. Larson has dark hair and brown eyes, but he, too, looks as if he could be Stephen’s biological father. When together, they definitely look like a family, even down to their clothes; they all wore oxfords, khakis and loafers for a recent portrait.

The questions they get come mostly from Stephen’s friends and classmates and have more to do with family structure than adoption. “Where’s your mommy?” they’ll ask. Or, “Why do you have two daddies?”

Stephen knows his story. He lived with his grandmother before entering into foster care, and he remembers those years. He has a photo album with pictures of her holding him as a baby that he likes to look at with his fathers. He’s 7 now, and the main question he has is why he was put into foster care.

“Your grandmother loved you so much that she wanted the very best opportunities for you,” Ensinger and Larson tell him. “She wanted to find a stable, loving family for you that could provide you with more than she was able to.”

He still struggles with that question and maybe always will, but the questions about his two Dads don’t faze him at all. As he gets older, the questions surrounding sexual orientation will inevitably come up, and Ensinger and Larson, like other same-sex adoptive parents, will address the topic each time it’s raised and add as much information as Stephen is mature enough and able to understand.

The couple has worked hard to ensure that Stephen is comfortable with his story because if he feels OK about his situation, others are likely to as well. And Stephen is pretty comfortable most of the time.

“He’s a resilient kid with a very big personality who loves being the center of attention,” says Larson, who admits to being the rule maker and disciplinarian in the family. “When someone asks if he has two daddies, he just says yes, and off they go to play. It’s just innocent curiosity.”

They haven’t been asked intrusive questions by adults and say they feel completely accepted by the community, which they recognize is more progressive than some. “We might not be saying this if we lived in Idaho or Montana,” says Ensinger.

Still, living and parenting as a same-sex couple has not been without its challenges. Ensinger and Larson were married legally in California, but until last October, their marriage wasn’t recognized in the Commonwealth.

“I’m still not Stephen’s legal parent, so I’ve needed a phone call or a note from Peter before I could do all of the things any parent ought to be able to do, like taking him to a routine doctor check-up, visiting him in the emergency room or making medical decisions for him,” says Ensinger. “It’s been incredibly frustrating.”

Fortunately, that aggravation will soon come to an end. With same-sex marriage legal in Virginia as of October 2014 and the Attorney General recognizing out-of-state marriages, Ensinger has applied to be the second parent. Now it’s simply a matter of time. And things will hopefully be more streamline the second time around. As this was going to press, Ensinger and Larson were fostering another boy, Robbie, 11, who they hope will soon become a permanent addition to their family.

While they wait, they blow off steam playing tennis and taking family trips to the beach and to their mountain house in West Virginia, and often travel to visit family in San Francisco, Philadelphia and France.

They also find support from their church congregation and their community.

The first time the couple brought Stephen to St. Alban’s Episcopal Church in Annandale, people crowded around them with excitement.

“The response was so amazing. There were even a few people who came up to us and said, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m adopted, too!’” says Larson, a self-proclaimed “joiner” who is on the Stewardship, Holiday Bazaar and Young Family Connections committees at church.

When Stephen’s adoption was finalized, their priest wanted to have a ceremony to recognize the new family at church and to baptize Stephen. They wore their Sunday best, and the priest blessed the three of them in front of the congregation. They even appeared in the church newsletter.

“When we adopted, we were drawn into the church even more closely because of the shared experience of parenthood and the shared responsibility of raising our children together,” says Ensinger. “And now Stephen has become kind of a pseudo-celebrity at church. He has a very outgoing personality and has been called the mayor of St. Alban’s.”

Following the adoption of a child, their church encourages families to contact one of the clergy to schedule a “Thanksgiving” (found in the Book of Common Prayer on p. 439), a short prayer and blessing ceremony that occurs during a regular Sunday morning service. It allows the congregation to welcome that child into its midst and to honor the changes taking place in the family with the arrival of the new member.

Unfortunately, not all churches are the same.

Mary Alice Heretick, 52 is also from Falls Church and is the single mother of 8-year-old Virginia LiRoon, or Ginnie-Li, whom she adopted from China. They have attended the same Catholic church for years, but Heretick doesn’t feel supported by her priest the same way Ensinger and Larson do.

“My Catholic church prays for fathers and mothers—the ‘traditional family’ as it was called one Sunday,” says Heretick. She feels excluded from the ministry and once asked her pastor if maybe they should be praying for all families, regardless of how the family looks, as a way of being more inclusive.

“The discussion with the pastor didn’t work; the next Sunday, we prayed again for mothers and fathers,” she says. “My church even had a priest come from Africa, and we prayed for him, but for some reason the church can’t include prayer for nontraditional families. The Sunday we prayed for the African priest, I left the church in tears during the service wondering why we can pray for someone whose ministry is halfway around the world, but we can’t be more inclusive in our little corner of the world.”

Heretick’s experience illustrates that even in progressive areas like Northern Virginia, there is still a persistent mindset about how families should look. Parenting is hard for everybody, but excluding a single parent from ministry teaches her child that her family isn’t as good as another type of family.

Tips from Adoptive Mom Bonnie Gardner

1. Rather than asking how much an adoption costs, ask what is involved in the adoption process. If you aren’t genuinely curious about the process and just want to know how expensive it is, be tactful. Don’t ask. If Gardner senses that the question is genuine, she tells people that there is a lot of paperwork and associated fees, and it’s very tough but not impossible.

2. Don’t ask about a child’s “real” mom. Use the term birth mother.

3. Adoption is a very personal choice that people come to for very different reasons, but never assume it’s because it’s trendy and that adoptive moms want to be like Angelina Jolie. People adopt because they want to form a family just like anyone else who has children.

4. We live in America, but we are all citizens of the world. Children from every corner of the globe need homes. Don’t ask why an adoptive parent didn’t adopt domestically. Celebrate all forms of adoption.

5. Give adopted kids a chance. They don’t all have ADHD or attachment disorder. Don’t listen to all of the high-profile horror stories. Adopted kids are wonderful kids.

Heretick says Ginnie-Li is confused by what happens at church each week.

“She recently said to me: ‘Momma, you’re my momma. The church prays for other moms and dads. Why doesn’t the church pray for you, too?’” says Heretick. “Unfortunately, I have no answers.”

Even though it’s her neighborhood church where Ginnie-Li received First Communion, they are looking for another Catholic church in Northern Virginia.

“We will find one that’s much more receptive to different types of families and one that doesn’t require me to be married in order for me to be regularly included in the Mass,” she says.

Heretick also seeks other opportunities to find families that look like hers: Caucasian parent, Asian child. They belong to a group called Asia Moms, almost all of whom are single moms who’ve adopted from China. Once a year, they attend “Chinese Camp” in West River, Maryland, with the Maryland Families with Children from China organization, and they always go to the Chinese New Year celebration put on by the D.C. Families with Children from China group.

She chose to live in Falls Church City because of the schools.

“The ‘Little City,’ as it’s called, isn’t as racially diverse as I’d like it to be, but we are centrally located, which enables us to attend events all over the D.C. metro area with families that look just like us,” Heretick says.

“The nuclear family is no longer the norm,” says Riley of CASE. “We need to celebrate all families in all the forms they come in, and we want to normalize adoption in the greater community so that kids feel good about where they come from and where they are.”

The sheer number of diverse family support and social groups indicates that Ward and June Cleaver are no longer the standard in Northern Virginia. You’ll find Single Mothers By Choice and Tribe, a group for multiracial, -ethnic and –cultural families. There is Asia Moms of the Metro Area for single mothers with kids from Asia, which Heretick belongs to; a chapter of Families with Children from China; Rainbow Families D.C.; Single Parents of Alexandria; and Faces of Virginia Families, which offers support groups throughout the area for foster families. There is Korean Focus, a support organization for families with children from Korea, and LAPA, which stands for Latin America Parents Association of the National Capital Region. The list goes and continues to grow.

“With so many ways to make connections, the D.C. metro area is a wonderful place to raise adopted children,” says Riley. “From the restaurants to the museums to the festivals, we have so many opportunities to experience and learn about other cultures. And with so many adoptive families living here, families can find others who look like them, which offers kids a chance to not feel so different. They can fit in and feel good.”

(March 2015)