Wolf Trap is the kind of concert venue where you can see Jennifer Hudson, Nas, or Seth MacFarlane alongside the National Symphony Orchestra—in the same night. It might host the American Ballet Theatre in the same week as Kesha. And don’t be surprised if a cottontail rabbit hops down the aisle during a show or squirrels frolic a few feet away, though the wolves that were once so abundant here that they inspired the place’s name have long vanished.

This July marks half a century for the country’s only national park dedicated to the performing arts—from rap to the symphony, from bluegrass to Broadway musicals, from stand-up comedy to ballet. Its partnership with the NSO, which provides backing instrumentation for popular music acts, encapsulates Wolf Trap’s unique marriage of fine arts and pop culture. And it all unfolds amid 117 acres of Northern Virginia nature. Many of the biggest legends in show business have made the trek to Vienna to perform here, and presidents and royalty have come to watch them from the 7,028-capacity Filene Center, the half-indoor, half-outdoor venue with 3,800 seats under cover alongside space for about 3,200 people to spread out on the lawn.

“The first time we brought Sting in a few years ago, he came and did three nights. If all you want to do is make as much money as you can in the smallest amount of time, he could have played a 20,000-person venue for one night. But he did three nights with us,” says Wolf Trap president and CEO Arvind Manocha. “That’s always meaningful and shows a real commitment to the audience.”

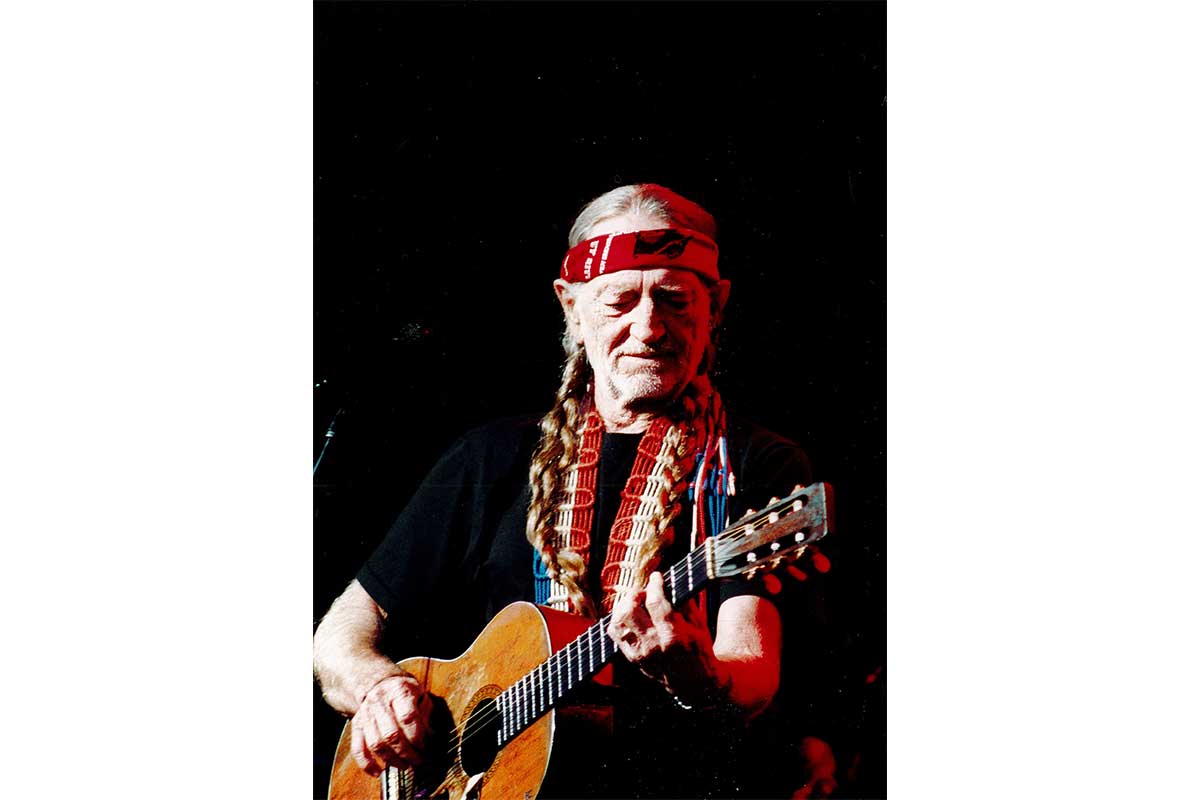

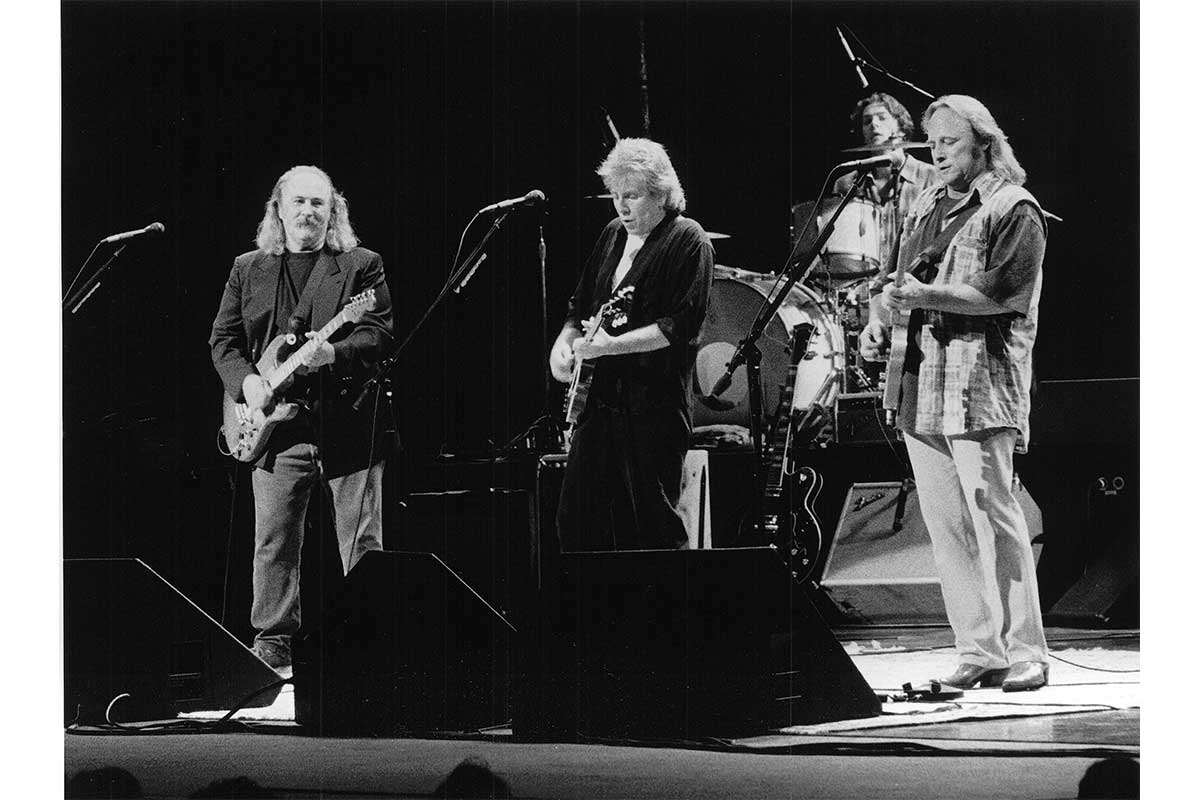

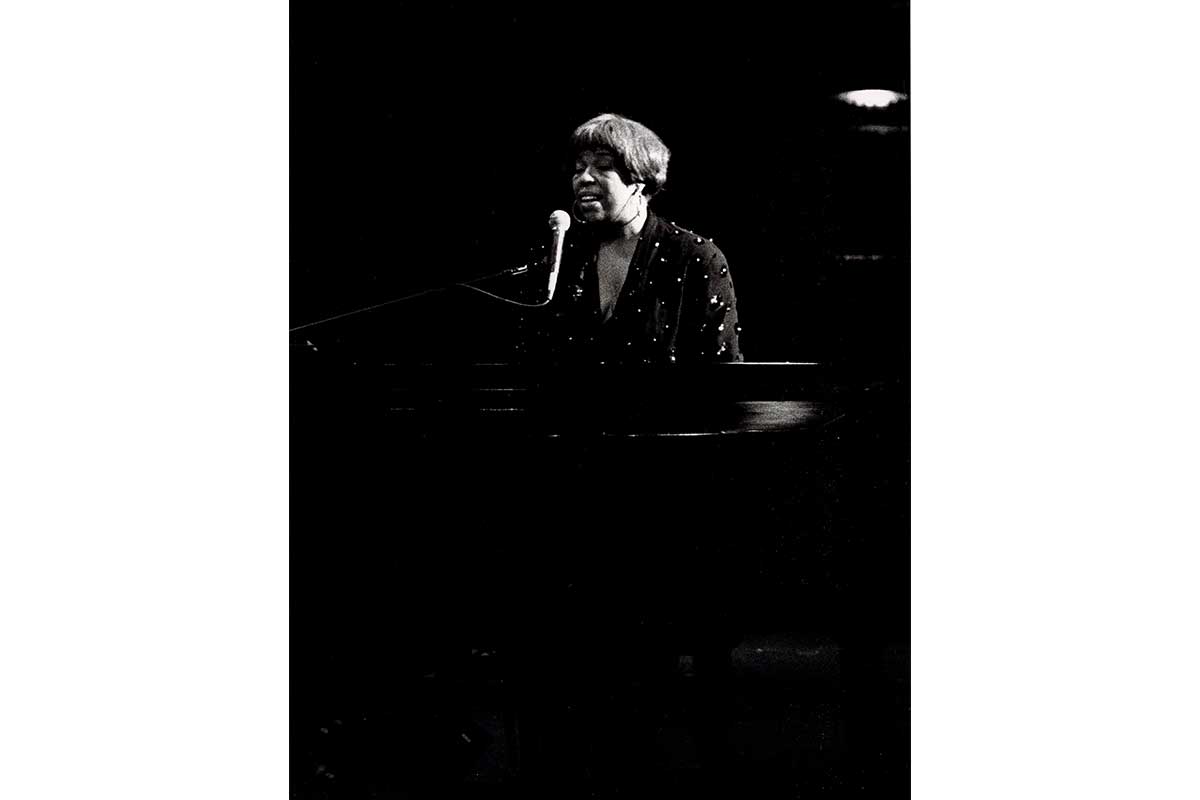

Over the decades, acts such as Bob Dylan, Ray Charles, the Beach Boys, Aretha Franklin, Ella Fitzgerald, Tony Bennett, Dizzy Gillespie, Paul Simon, Diana Ross, Dolly Parton, John Denver, Willie Nelson, Whitney Houston, and Ringo Starr have trooped through the Filene Center. At the same time, the performance hall features some of the biggest modern pop acts, hosting Demi Lovato, Meghan Trainor, Charlie Puth, Halsey, and Carly Rae Jepsen in recent years. And it never forgets the fine arts—2016’s Romeo and Juliet and 2019’s Swan Lake, both featuring ballet superstar Misty Copeland, rank among the highest-demand shows Wolf Trap has produced in recent years.

“We staged Puccini’s La Bohème in 2009 with the NSO on a beautiful night: 80 degrees, no humidity. We had also staged [’90s Broadway musical] Rent earlier in the season, which is based on La Bohème, but the two endings are very different. I heard a woman behind me turn to her friend and say, ‘This isn’t how it’s supposed to end!’” says vice president for opera and classical programming Lee Anne Myslewski. “It was a good reminder that people are dovetailing this older art form with newer art forms.”

The NSO also joins the centuries-old art form of symphony with the newer art form of movies. Several times each summer, it performs iconic scores alongside the original films, projected on a massive screen. In recent years, the titles have included La La Land, Jaws, Jurassic Park, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and several installments of the Harry Potter series. For one song during Star Wars, conductor Emil de Cou even replaced his baton with a lightsaber.

Old acts, new acts, fine arts, the movies—you can find these things at various other venues, too. But Wolf Trap brings them all together, and as a national park, it also boasts scenic hiking trails and outdoor opportunities, providing a unique blend of nature and the arts. Even if the main attraction is a performance that night, many concertgoers make a whole day of their visit to Wolf Trap by hiking, birdwatching, and bringing a picnic to the lawn to enjoy as the sun sets.

The history

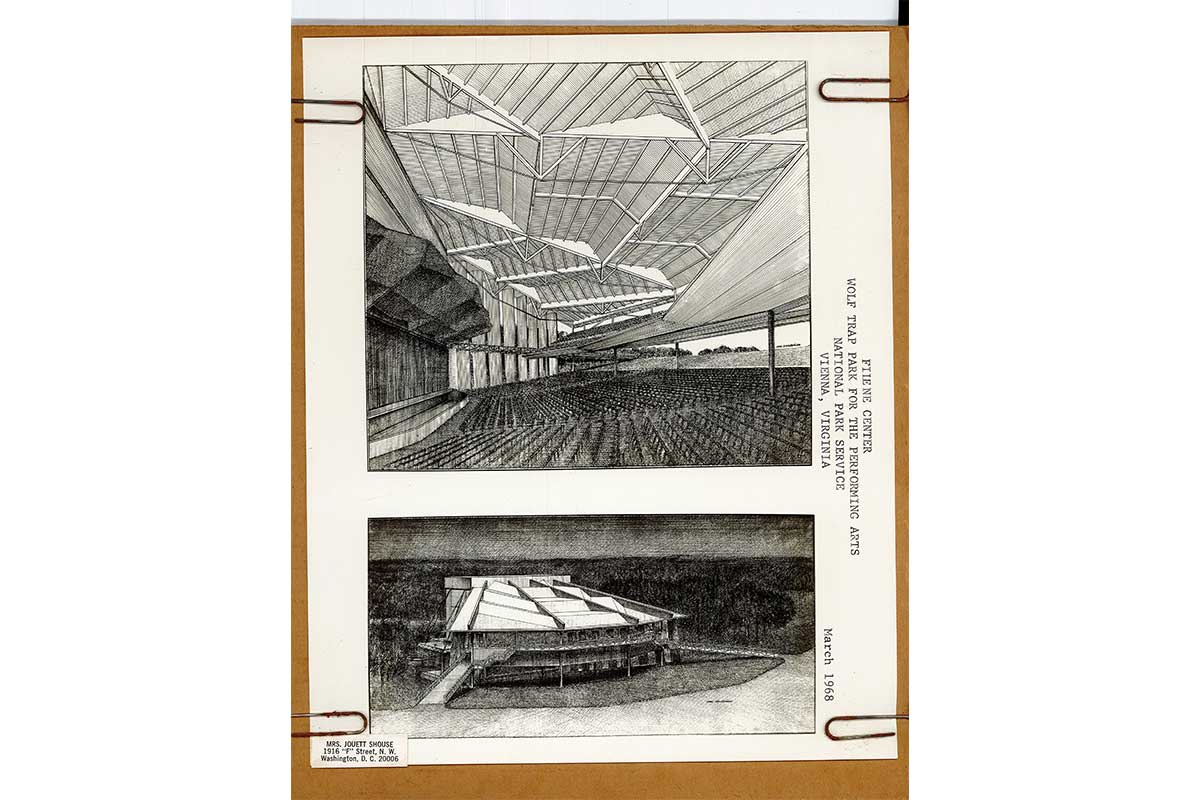

All of this started with a visionary woman: Catherine Filene Shouse, who held a Labor Department position at the age of 21, in 1917, and was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1994. She was the granddaughter of William Filene, founder of the department store Filene’s. In 1966, Shouse donated almost 100 acres of her Northern Virginia farmland to the U.S. Department of the Interior, along with the funds to build a large outdoor amphitheater.

But even that didn’t make the national park a done deal. “JFK had appointed a courageous interior secretary named Stewart Lee Udall, who was retained by LBJ,” says former National Park Service director Bob Stanton, who now lives in Fairfax Station and still frequents Wolf Trap. “It was Udall’s vision and enthusiastic support that really gave the indication to members of Congress that they should enact this legislation.” In 1966, the House of Representatives voted to create the national park, 195–105.

Wolf Trap formally opened to the public five years later. The debut shows on July 1 and 2, 1971, starred several acts, including pianist Van Cliburn, the U.S. Marine Band, and New York City Opera star Norman Treigle. (Treigle’s granddaughter Emily will perform at Wolf Trap this summer, stepping into the title role in Holst’s opera Sāvitri.)

That August, Richard and Pat Nixon attended a performance of Musical Theater Cavalcade, a revue featuring numbers from various musicals. “I thought it was a great show,” the president told The New York Times that night. “Without question, there will be some great stars produced from this company and from others like them.”

Shouse remained a frequent fixture at shows through the years before passing away in 1994 at the age of 98. Annie Coppola, director of planned giving, remembers Shouse writing a personal thank-you letter to a donor who gave a relatively modest $25 in 1978. “She would always ask people at a show, ‘What was your experience tonight? Where did you park? Did you bring a picnic?’” says Coppola. “She was always thinking about how we could engage.”

The challenges

Running a world-class performance venue in the middle of former Virginia farmland isn’t always a walk in the park. That’s especially true because Wolf Trap isn’t devoted exclusively to the fine arts. For instance, at a venue like the Metropolitan Opera in New York, a typical performance will run from seven to 21 performances. For Wolf Trap’s 2018 production of Verdi’s Rigoletto, they built an entire production and set at the Met’s scale, but for only one night.

Simply getting out to the sprawling park in Vienna can be difficult for some would-be visitors, who make the pilgrimage from around NoVA, DC, and beyond. In the 1980s, to improve accessibility for those who do not own a car, Wolf Trap and Fairfax Connector added a shuttle bus to and from the West Falls Church Metro station for $5. The system isn’t foolproof, though: When taking the train to Wolf Trap in 2019, Wait, Wait … Don’t Tell Me! host Peter Sagal was almost late to his own show because he’d loaded 25 cents too little on his SmarTrip card.

Some complain that the lawn is too steep, with one patron telling The Washington Post that he spent his one and only lawn experience “trying to keep from rolling down the hill.” (He has paid to sit in the house seating ever since.)

For years, though, the biggest obstacle Wolf Trap had to overcome was when a fire completely destroyed the Filene Center on April 4, 1982. The fire’s cause and origin were never conclusively determined. With only six weeks until the summer season was set to kick off, Wolf Trap managed to build a temporary 6,500-seat structure in record time. The reconstructed Filene Center opened in 1984.

Still, nothing compared to last year, when the pandemic shut down its entire live schedule. Forced to keep its stage empty, Wolf Trap turned to streamed virtual performances instead. One such stream showcased opera songs inspired by woodland scenes in shows like A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Hansel and Gretel, performed outside in the park’s actual woods.

Wolf Trap also doubled down on its Early Learning for the Arts program, which uses techniques from music and dance to help teachers advance curriculum objectives in preschool, kindergarten, and first grade. For example, the lessons point out the correlation between dance patterns and simple geometry, applying the concepts of spatial relations in choreography to shapes. Around 90 percent of the participating schools last year were Title I, the Education Department’s designation for schools with a higher proportion of underprivileged children. The program actually delivered more education services in 2020 than in 2019.

The future

The bright side of an otherwise all-around awful year? “We acquired more than 1,000 new donors in 2020, which is shocking during this time when you’re not really that active,” says vice president of development Sara Jaffe. “It speaks to the legacy of Wolf Trap. While last year was really difficult, philanthropy was a silver lining.”

This comes amid a positive longer-term trend for Wolf Trap’s financials. In the past decade, its membership base approximately doubled, while money raised more than quadrupled, says Jaffe. That kind of largesse from corporations, foundations, and individuals is essential because ticket sales alone aren’t usually enough to cover all the costs of bringing an act on stage.

And yet they’ll keep coming.

“I always like meeting people who say, ‘I look at Wolf Trap’s calendar when you announce the shows; I pick five that I love and three more that I’ve never even heard of.’ Because they know we’re going to do something good,” says Manocha, the CEO, with a grin. “Or meeting people who say they used to come to our Children’s Theatre-in-the-Woods, and now they bring their children. After years and years, it becomes a family tradition. That is always gratifying.”

Fifty years, he figures, is just the beginning.

“The National Park Service is really in the ‘forever’ business,” says Manocha. “So in that sense, 50 years is just one step toward forever.”

This story originally ran in our July issue. For more stories like this, subscribe to our monthly magazine.