It’s taken 70 years, but it would seem every square inch of wall space at JV’s Restaurant in Falls Church is adorned with a photo, portrait, memento, souvenir, ironic street sign, zombie mask or odd patriotism-themed objet d’art to the point where putting something new up would require adding a wall, which is what happened a few years ago, but let’s not get ahead of things.

Lorraine Campbell is the owner of the joint, and at 66, she’s been coming here her entire life since her father and her uncle opened it in 1947, four years before she was born. The Jefferson Restaurant, as it was known then, might have been in her life her entire life, but her parents kept little Lorraine and her sister, Pauline, away from the business as long as they could, until they were teens and could help with the dishes.

The festive decorations that festoon the walls and the bar and the booths and the bandstand are not the store-bought flair calculated to evoke a neighborhood vibe like you find in Applebee’s. Everything in here is here for a reason, with most of the items given freely to Campbell over the decades, usually because a regular customer—and most of the customers seem to be regulars, many of them for subsequent generations—wanted Campbell to have it and gave it to her with a heartfelt sentiment.

So one day during happy hour, sitting in a booth on the east side of the room a few hours before the band plays and the swing dancers dance, we ask her: If the place was on fire, heaven forbid, and everyone was out and safe, and she had one chance to run inside the burning building and grab the thing most important to her, what would it be?

There is a long pause, which is unusual for the loquacious Campbell, who is chatty without being gossipy, earnestly down-to-earth and guardedly friendly—a consequence of being a lifer in an industry that makes you initially wary of strangers.

Would it be the 3 ½-foot-tall oil painting of Campbell wrapped in a feather boa and seated on a Harley-Davidson motorcycle bearing the JV’s logo, a gift from the artist? One of the Plexiglas-encased electric guitars autographed by multiple musicians and donated after charity benefits?

The pause grows longer. She looks around the room. Then, finally:

“What would I grab?” she asks, repeating the question. “I probably wouldn’t come back out.”

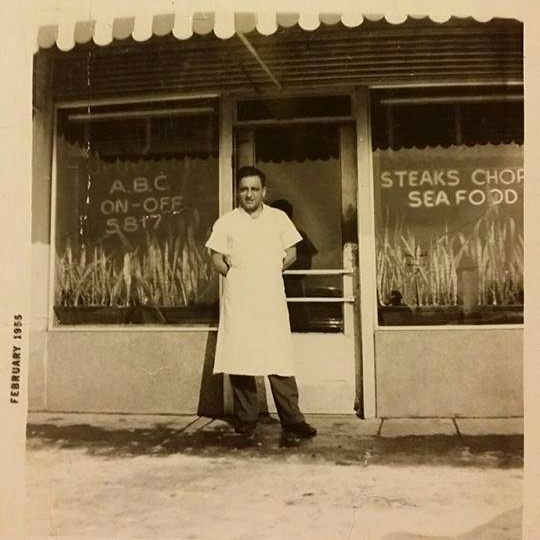

In 1947, hard as it is to believe now, Route 50/Arlington Boulevard was a two-lane road, hardly the megahighway it is now, with some barely paved stretches west of Falls Church. The first strip shopping center outside of D.C.’s city limits was erected on Route 50, and that’s where George and Louis Dross put their establishment, the Jefferson Restaurant. (The name was changed in the 1960s to reflect the name of the center, Jefferson Village, thus, JV’s.)

The original restaurant—the phone number, in the style of the day, was Jefferson 4442—with its steamship rounds of beef hanging in the front window, had some 26 employees in starched white liveries serving hearty meals to a robust post-World War II clientele that was settling into newly developed neighborhoods in Arlington and Falls Church.

Eddie Fisher, the late Debbie Reynolds’ husband and Carrie Fisher’s father, used to frequent the joint when he was stationed at Fort Myer in Arlington, as did plenty of other soldiers. The jukebox and the food must have been the main attractions because the place did not sell booze and never has—beer and wine only and, at some points, not even wine. Campbell tells the story of how Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control had a draconian size requirement for the tables in establishments permitted to sell spirits. The Dross’ tables were off by an inch. “My father said forget it,” she says.

The wine is back and has been for 20 years, and there’s bottled beer, no draft, and Campbell doesn’t even entertain adding booze to the mix.

Two years ago the longtime Asian pharmacy next door moved out, and Campbell did what every musician, dancer and music fan of the room fantasized about for 68 years: She expanded. It took a year to knock out the wall and double the size of everything—the bandstand, the wooden dance floor, the now-horseshoe-shaped bar—and add a new wall for even more memorabilia.

Booze? Nah. Campbell would rather focus more firmly on her main passion and the main draw to JV’s: the live music.

Remarkably for a suburban location catering to an older demographic, JV’s stays open every night until 2 a.m.

“And the kitchen stays open until 2,” she quickly adds. Every item on her newly expanded menu—from the meat loaf (a favorite of Louisiana bluesman Tab Benoit) and lasagna to the gravy fries and chili—is available to hungry customers well past the hour when the late-night TV shows have called it a night.

Campbell stays to the end every night, she says, locking the doors and getting the place ready for the next day with the staff (there are about 15 employees that keep the place running). When all that is done, she gets to her home in Manassas (about 25 miles away) at 3:30 or 4 a.m. and promptly hits the sack. “I make sure I get my eight hours of sleep,” she says.

Campbell is 5 feet 2 1/2 inches tall, but her blonde updo and her larger-than-life personality make her seem taller. Given her demanding industry—running a restaurant is brutal enough; running a music nightclub is masochism—and her hours, Campbell is remarkably clear-eyed, smooth-skinned and undoubtedly enthusiastic for the details of her business.

When noon rolls around the next day, Campbell is back at it, doing what bigger venues have multiple employees assigned to do: updating the restaurant website, negotiating dates and deals with incoming talent, ordering the food and beverage, figuring out the merchandise inventory and doing the marketing to promote the shows.

Maintaining the 4,000-person email list and promoting the shows are vital because with few exceptions, the bands, as consistently competent as they are, are largely unknown but to their own fans.

Campbell did assign someone to be in charge of band posters, a manager who makes sure that the bands send them ahead of time and that they get taped to the walls, particularly in high-visibility locations in the restrooms.

“I’m anal about posters for musicians,” she says, pointing to the latest gallery of 8-by-10 flyers taped to the ladies’ room mirror and walls.

The website listings and the posters are just about the only promotion a band can expect at JV’s, despite trying. Mainstream music publications and critics do not preview or review the acts the way they do on occasion for, say, Jammin Java in Vienna, the Birchmere in Alexandria or Iota in Arlington.

Bands bring their own “house” to their shows, using their own mailing lists and social media outlets to generate excitement. The band gets the cover charge taken at the door—on weekends the doorman is likely to be Campbell’s son, Mac—and keeps the tip jar affixed to the front of the stage. (Her daughter, Paulette, also works at the club, behind the bar, and has for more than 20 years.)

That cover charge is likely to be anywhere from a few bucks for a local outfit to $10 for a nationally touring act. “But we seldom do that,” she says. It’s more likely to be a few bucks. And if you feel generous, buy the band’s self-financed CD between the three sets of music while you are at it.

The fee tops out at the rarely charged $15 for international acts, and they do get them once in a while because Campbell’s place is well-known among musicians who might just need gas money to get to the next big gig out of town.

“I’m always willing to help anybody out,” she says of her reputation among musicians. “But there’s a quality of music I like to keep in here. I don’t necessarily dislike garage bands—some are OK—but the quality of music I like to have is more professional, experienced. You can count on coming in at any time and hearing good music. And there are a lot of great musicians around here.”

The musicians respond in kind. They “play” the room, keeping the vibe going without self-indulgence, they respond to the audience, which is generally receptive and appreciative, and because the music is why they are there, the crowd focuses on what’s on stage, not what’s on television (though there are a few muted flat-screens over the bar).

Small live music venues like JV’s are increasingly rare, not just in Northern Virginia but in the country as a whole. Musicians on a stage with Fender Telecasters and Rhodes electric pianos and multipiece drum kits are the exceptions in these days of DJs with prerecorded beats and electronically enhanced samples on a jump drive plugged into a laptop.

“Honky-tonk roadhouses are a dying breed,” says veteran area guitarist Dave Chappell. Chappell’s album Dave Chappell & Friends won the 2016 Best Roots Rock Recording and Best Debut Recording from the Washington Area Music Association. He has 21 Wammies in all, including 10 in a row for Roots Rock Instrumentalist. He’s now given emeritus honors so others can win.

He plays JV’s—which, in fact, won the first Special Appreciation Wammie, in 2004— just about weekly, either with his own ensemble or with someone else’s. JV’s, he says while plugging in his Telecaster before a recent show, “is an endangered species. We need more places like this for our working bar bands, but the bar scene has changed in general. It’s kind of rare these days to be doing what we were doing way back when.”

As for Campbell, whom he has known for decades, he has nothing but admiration. “She books a wide array of music because people, not just her, like different things. She invites people from all over the country and gives them a try. And she’s totally hands-off—you can do your own thing as long as you bring people in here.

“She’s an easygoing den mother who’s supportive,” Chappell says.

“She’s an amazing gal,” says Johnny Castle, another veteran area musician. He’s the bassist in the iconic blues-rock band the Nighthawks as well as with the Thrillbillys, the power pop ensemble that keeps the dancers moving at JV’s on monthly Thursdays.

“I can’t believe she doesn’t get jaded,” says Castle, who, as a member of a touring outfit like the Nighthawks, has seen his share of jaded nightclub promoters. “Having to fill a place night after night … I’ve never seen her disgruntled. She’s always got time to talk to the musicians; she’s always enthusiastic.

“I get beaten down by the road, I really do, but I get rejuvenated at JV’s, and I’m not just saying that,” Castle adds. “I walk in there, and I’m home.”

David Kitchen, the guitarist who founded the Thrillbillys, has been playing JV’s since the late 1980s. The venue, he says, “is an extension of Lorraine. She’s so unpretentious. She’s nurtured this local scene and created a good hang. She mixes it up with blues, country, rock, soul, whatever and likes it when bands play off-the-wall stuff or stretch it out. And she’s there for every single gig.

“As a musician, something about the feel of the place and knowing how much great music has been made there makes you play better,” he says.

This is sure to be music to Campbell’s ears. She says the long hours and overhead headaches (increased rents, county licensing, the endless list of things to do) are all worth it because of the music. And the musicians.

Although her booking policy is not based on charity, she’s aware of the live entertainment landscape. “I know so many wonderful musicians who find it hard to get a job because they’re older and don’t play what’s on the radio,” she says.

As for her own interest in live music, well, she says: “I can’t go out, so I bring the music here, seven nights a week, sometimes 10 shows a week. We’re all about the music.”

The music is what it’s about, and be that as it may, what is it with all the Prisoner of War stuff hanging on the walls? There’s a lot of it, and it makes you wonder.

Tucked into a tight corner near the front door is a large-ish wooden model of a Vietnam jungle prison camp, the kind Rambo blew up like toothpicks in Rambo: First Blood, Part II. A black-and-white photo of George Dross is built into the box that holds the model.

Across the room, dangling like a giant mobile from the ceiling, are large POW engraved dog tags.

There’s an oversized silhouette of a soldier kneeling at a gravesite along one wall. The logo for Rolling Thunder, the national motorcycle caravan-tribute to POWs and Missing in Action soldiers, adorns some of the JV’s-branded merchandise.

Just about everywhere the eye rests, if it’s not an American flag, a zombie mask, an autographed photo of a musician, an autographed electric guitar or a sign with the venue’s from-the-heart motto—“Ageless Charm Without Yuppie Bastardization: Est. 1947”—then it’s something to do with POWs and MIAs.

“Our family has always been patriotic,” Campbell says, as if that explains everything.

Actually, the origins of that patriotism, and the reverence for prisoners of war, involves Nazis.

George Dross, Campbell’s father, was a Greek dental student when Germany invaded Greece at the outset of World War II. In taking his small town, German soldiers slaughtered anyone who might be a threat, including a young dental student. Dross was left for dead in the street, shot in the back.

But Dross was only wounded, and after members of the Greek Resistance got him back to health, he joined the cause. The Dross family took in wounded soldiers, including Americans, but it didn’t last long as Dross was captured by Mussolini’s Italian forces.

The Italians were not kind to their prisoners, and Dross was tortured. But before the worst could happen, British paratroopers helped him escape. Dross remained too close to the action and was captured again, this time by Nazis.

“He was held as a servant for a Gestapo—but the Gestapo was against the war,” Campbell says of the German officer. Not only did Dross survive the captivity, but the Gestapo also gifted him items that Dross would later sell for his passage to the United States.

In all, Dross was a POW for 18 months. His experience, and the meaning of it, has been handed down to his children. And that’s not all.

“You know,” Campbell says, remembering, “I still have the electric train set the German officer gave my dad. I have no idea what it’s worth.”

George Dross met Campbell’s mother, Diane, at a social in Delaware, and during their first dance he assured her they were going to get married.

Then a thought occurs to Campbell.

“If the building was on fire and I could get something out, it would be that model prison.”

(May 2017)