Cold Cases

Right from the start, there is lots of missing information that could help a detective connect the dots. “There is a danger in the investigation,” Prince William County Cold Case Detective Brian Coady says. “And that danger is tunnel vision. Sometimes you don’t get to see the whole picture.”

“That is the lament of a real cold case detective,” Loudoun County Cold Case Detective Steven Schochet says. “We didn’t recover the evidence. We are getting it years later. What’s left? What’s been damaged due to time? Is the suspect dead? We have no knowledge of that.”

Those cold cases you see on television? Complete fiction. “Because in 30 minutes they solve a cold case,” Detective Schochet says. “And people, I hate to say it, believe TV. We are digging every day.”

These cases, for the most part, become cold as a result of missing persons cases. Someone reports a loved one missing. Police fill out reports, gather evidence, then try to decide if that person is missing by accident, missing on purpose, or lying dead in some remote area as an undiscovered homicide victim.

Detectives know instinctively that the majority of these cold case homicides are a result of crimes of passion, and, in some cases, happened because a burglary or drug deal took a turn for the worse.

“Most people die at the hands of someone they knew,” says Coady, who knows a thing or two about the dark side of human nature. He worked patrol for the first five years he came to the Prince William police force in 1999, then moved into the violent crimes division handling shootings, stabbings, murders and rapes before being assigned cold cases two years ago. “The murderer is not typically a stranger,” he says. “And I do sometimes think about why someone murdered someone. It may not make sense to us. But for them, at that moment, it made sense to them.”

Being a cold case detective is a tough profession, staffed by trained investigators who have to be patient and believe in every lead and follow it no matter where it looks to be going, because they know going into a case they are not going to get a success every day, or even every year.

That frustration they feel gets worse as time goes on, especially because they can’t find the resolution they want to find for the loved ones who lost a daughter or son or mother to a senseless murderer. Then, over the years, witnesses, perpetrators and family members get old and die off. Many leads end up going nowhere.

Those dead ends can be the toughest part of the job, Coady says. He recalled a case where he thought he had his guy. “Too many things lined up with his history, his past, his work and his location. But we had DNA in that case and it didn’t match,” he says. “That was a blow to the gut.”

It’s the families that really pay the price, Coady says, and that keeps driving detectives on to do the best they can with what little evidence they have. “I have cases dating back all the way to the early 1980s,” he says. “And the wife of this one gentleman contacts me on the anniversary of his murder. And that is a sad time. Every year I dread getting that phone call because [she] want[s] to hear new information. And I can’t give [her] anything that is new.”

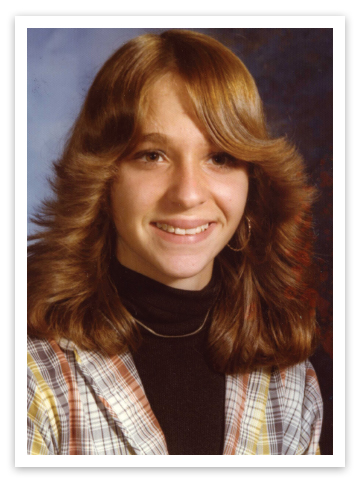

Whatever happened to 18-year old Cynthia Joan Gastelle is one of those whodunit cases Coady is handling. She was reported missing to the Takoma Park police in Maryland by her family on April 3, 1980. On February 12, 1982, Prince William police found skeletal remains on Bull Run Mountain off of Mountain Road in the Haymarket area. Investigators didn’t know who she was, where she came from or how she got to where she was found. “They had a possibility of how she died but it wasn’t a concrete sort of thing at the time, where it was enough to know it was murder,” Coady says.

It wasn’t until recently when a cold case grant program from the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) enabled investigators to compare missing persons cases with random skeletal remains found in the region. In 2005, NIJ awarded a total of $14.2 million to 38 state and local agencies; and in 2007, the Institute awarded another $8 million to 21 state and local agencies.

Investigators collected the Gastelle family’s DNA when there was another skeleton found in Richmond, thinking maybe that was their daughter. It wasn’t.

But in May 2012, the DNA collected from the Gastelle family matched the skeletal remains of the Prince William County’s 30-year-old unsolved case. “That was a good day for us,” Coady says. “Unfortunately, you never want to tell the family bad news, especially when they had hopes that [their daughter] was still alive.”

There is no evidence of the perpetrator in that case, though they do have a picture of a former boyfriend who they consider a person of interest.

Alisha “Lisa” Johnson was last seen on Sunday, July 28, 1996, in the 600 block of Four Mile Road, in Alexandria. On Sunday, August 4, 1996, her body was recovered in Fauquier County.

(If you know anything about this cold case, call the Alexandria Criminal Investigations Section, 703-746-6711.)

Sparky Faulkner, mid-30s, was a house painter who dabbled in selling drugs. On September 6, 1984, Faulkner answered a knock on his door and was shot multiple times, falling back into the house. An investigator close to the case said that he lived “on the wild side,” had some female trouble and was seeing a married woman at the time of his death. Investigators had a couple of witnesses that heard a car with a loud exhaust drive off. Investigators believe that this was not a random killing, but may have been a retaliation murder that had something to do with drugs.

(If you have any information about this case, call the Loudoun Crime Solvers at 703-777-1919 or 1-877-777-1931.)

Erica Heather Smith, 14, disappeared on July 29, 2002. Her body was found eleven days later in a grave along the Broad Run Creek near an old pump house. The area is in Ashburn near the intersection of Beaumeade Circle and Loudoun County Parkway. It was a chance encounter with Erica’s father, Pete, on the campaign trail when new Loudoun County Sheriff Mike Chapman and her father first met. “He started talking about his daughter’s case,” Chapman says, “and I could see that, even nine years later, the anguish he was still suffering.” It was at that point that he decided to create the cold case unit (in early 2012) at the Loudoun County police department. In the summer of 2014, police linked a suspect to the crime. Unfortunately, the suspect in that case committed suicide without confessing. “We were closing in and we felt like, wow, we are going to make an impact and then your suspect dies. It’s kind of deflating. That was very difficult for everyone involved.”

(If you have any information about this case, call the Loudoun Crime Solvers at 703-777-1919 or 1-877-777-1931.)

Patricia Anne Moore, 10, went missing from 7359 Clifton Road in Clifton on July 5, 1970. She was reported to be going to visit a friend at 7408 Maple Branch Road. Her skeletal remains were found on October 10, 1970 at Rippon Lodge Estate.

(If you have any information about this cold case, contact the cold case unit at 703-792-7279 or the Crime Solvers Hotline at 703-670-3700 or 1-866-411-TIPS.)

On August 21, 1998, 52-year-old Andrea Cincotta was found dead at the 1700 block of North Rhodes Street in Arlington. Andrea’s boyfriend found her dead inside the closet of their bedroom. There was no forced entry to the home and no obvious signs of a struggle.

(If you have any information about this case, call the Arlington County Police Department tip line at 703-228-4242 or Crime Solvers at 866-411-8477.)

On August 14, 1974, John Herse (age not listed) and his wife were walking back to their hotel from the Orleans House Restaurant in Rosslyn when three men approached them from behind and pushed Herse to the ground. When Herse rose from the ground, one of the suspects shot him. The suspects are described as three black males. The first was in his 20s, 5-feet-7-inches- to 5-feet-8-inches-tall with a slim build. He was wearing a black hat, glasses (regular or lightly colored sunglasses), a dark jacket (possibly leather, but not cloth) and a white t-shirt. The second suspect was also approximately 5-feet-7-inches- to 5-feet-8-inches-tall and slender, with a plaid coat. A detailed description is not available for the third suspect.

(If you have any information about this case, call the Arlington County Police Department tip line at 703-228-4242 or Crime Solvers at 866-411-8477.)

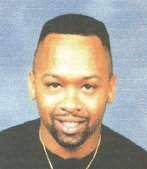

Darnell Brown, 22-year-old Maryland resident was shot on September 22, 2007. At 4:04 am, police were called to the 400 block of North Columbus Street in Alexandria for a man bleeding in the street. Upon arrival, officers found the victim lying in front of 409 North Columbus Street suffering from a gunshot wound.

(If you know anything about this cold case, call the Alexandria Criminal Investigations Section, 703-746-6711.)

Curtis Fitzgerald King, 27-year-old. On August 21, 1994, at 9:43 pm, police were called to Alexandria’s 6100 block of Edsall Road by residents who heard several shots fired in the area. Upon arrival, officers found the victim lying in a parking lot of the Edlandria apartment complex suffering from several gunshot wounds.

(If you know anything about this cold case, call the Alexandria Criminal Investigations Section, 703-746-6711.)

Charles William Monroe was reported missing on May 8, 2005, after a fire destroyed his apartment inside a barn located at 20215 Edgewood Farm Lane in Purcellville. Investigators searched extensively, but were unable to locate any human remains in the fire. He is described as a white male, 6-foot-3 inches, thin build, with blue eyes and brown hair. He was 35 years old at the time of his disappearance.

(If you have any information about this case, call the Loudoun Crime Solvers at 703-777-1919 or 1-877-777-1931.)

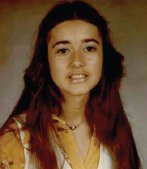

Karen Scarbrough, 17, had just graduated from Stafford High

School and started her first job at the Ryland Homes sales trailer at the end of Dale Boulevard in Dale City. Her body was found in the trailer along with two other women (Sharon Inboden Lake, 25, and Deborah Werner Frank, 23) at 6:45 p.m. on June 24, 1978. All three were shot execution-style.

(If you have any information about this cold case, contact the cold case unit at 703-792-7279 or the Crime Solvers Hotline at 703-670-3700 or 1-866-411-TIPS.)

Amore recent case being handled by the Prince William cold case unit, a missing person case from 2010, is even more mysterious. “There isn’t a whole lot of information about that case,” Coady says. It was March 22 of that year when 23-year-old Shane Donahue of Nokesville disappeared. “The last person that saw him alive may or may not be a suspect. But there is no body, no nothing. Just poof … gone.”

When detectives have nothing to go on, there is always the shining light in the darkness in the form of DNA technology that continues to evolve.

Amy Jeanguenat, vice president and director of lab operations for one of the largest DNA labs in the country, Bode Technology in Lorton, says she gets calls every five years or so from cold case detectives. “They will say ‘Have you had any new technologies? Do you think some of the evidence is now suitable for testing when five years ago it wasn’t?’” she says.

Jeanguenat is the daughter of a biology teacher. She got into the field of DNA lab work to “have an impact on society while still being involved in science.” She has been a lead analyst of hundreds of challenging cases, including cold cases, and says that overall, DNA technology is moving in two directions. “One direction is the rapid DNA, where it can be more instantaneously obtained, creating a profile within an hour or hour and a half,” she says. “And it’s also moving in the direction where we are able to obtain more information from a sample, such as ancestry, which might be important for an identification case where you are not really sure who it is and where that person came from,” she says. “There will be other characteristics, like eye color and hair color, that we will be able to obtain from this testing in the future.”

Rape may have been involved, according to Loudoun County law enforcement officials close to the case, where the skeletal remains of 27-year-old Charlotte Powell were found on a hiking trail near the gas and power lines off of Shreve Mill Road on December 8, 1987. Her clothes had been removed, and her body was in a position indicating there may have been a rape involved, officials say.

Powell, described by her family as a free spirit who would disappear for weeks hitchhiking around the eastern mid-Atlantic seaboard, was last seen alive in July 1987.

The family filed a missing persons report about their daughter with the Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania police department. When the body of a twentysomething-year-old girl was discovered on the W & OD trail in Loudoun County, the Mechanicsburg police chief heard about it and contacted Loudoun County police. Dental records confirmed that their missing person was Loudoun County’s Jane Doe—Charlotte Powell.

Biological fluids like sperm and sweat and saliva are the best ways of identifying a perpetrator in the case of rape. But with nothing but bits of clothing and skeletal remains, as in the Powell case, the hope of getting a good biological fluid sample had been a lost cause.

That is changing, Jeanguenat says. “We have obtained sperm from samples that have been over 40 years old,” she says. “And sperm, of all other biological fluids, is a hardy material. But when items are out in the elements and are exposed to humidity and get wet, with sunlight coming down on them, it becomes more difficult to obtain DNA from those samples.”

She says that soon they will have the ability to do a DNA profile on a single sperm cell resulting in some sort of investigative lead. “Typically we need at least 100 sperm cells now to do a DNA profile that would be suitable for comparison. But maybe in the next five years our technology is going to improve to where we would be able to get some type of investigative lead based on just one sperm cell.”

Another Loudoun County cold case is that of 20-year-old Veronica Hepworth. Her partially clothed body was found by a passerby alongside a driveway in Loudoun County on February 25, 1982. She was last seen at 1:30 a.m. at a local bar, the Fancy Dancer Bar on Route 1 in Fairfax County, celebrating a friend’s birthday. Witnesses say a red pickup truck was seen near the farm where her body was left.

Investigators interviewed the owner of the bar and the bands that were playing at the bar at the time of her disappearance, even going to North Carolina to try and find one of the bouncers at the bar. He was already dead, and that lead evaporated.

Eventually they identified a boyfriend, but that turned out to be another dead end. They are pursuing another boyfriend that they believe she dated for about three weeks before they broke up. According to law enforcement officials close to the case, he may have been the last person to see her alive, but he is not a suspect at this time.

“We run down every tip we [get],” Loudoun County Cold Case Detective Dave Canham says, speaking generally about the work of cold case detectives. “We have gone all over the place on our cases. And you can’t grade tips from one to 10, because what if you are off by two and that is the tip you need?” he says. “But if you don’t go knock on the door and ask the question, you are not going to get any answer.”

Canham and his partner, Detective Schochet, both came from major metropolitan police departments to their jobs as cold case detectives—Schochet from Nassau County, New York, where he worked for 28 years, and Canham from the D.C. Metropolitan Police Department, where he came to work in the Loudoun County’s newly created cold case division four days after retiring from the D.C. department. Their instincts about people and their motives are well-honed. “You have to first go back to the plate and wait for the next pitch,” Schochet says. “That is part of our job, but we keep sloshing through it.”

“If we can give one family member some resolve, then I think this job is worth it,” Schochet says. “Because who doesn’t want to help a family have some closure about the death of a loved one or a friend?”

Yet another of the 12 cold cases in Loudoun County is the shooting death of Ursula Haberland on August 23, 2001. Haberland was a widow who lived by herself on Greengarden Road in Upperville, at the end of a long driveway where the house was hidden by brush overgrowth at that time of the year because everything was in full bloom.

The sheriff’s office released information in April 2004 saying they got a tip from the Fairfax County Crime Solvers tip line of two people alleged to be involved in the murder, and investigators conducted door-to-door interviews with neighbors. But there are no suspects yet.

Her daughter, Sabine Haberland Cray, director of communications and marketing at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, says her mother was a “very kind and wonderful human being. It was just such an unfortunate end to a beautiful life. She had given so much to so many. And then to have somebody come and steal her away from us.”

She wonders why the killer didn’t just tie up her mother—a 5-foot-tall, 100-pound, 81-year-old woman—instead of killing her. “The only thing I can think of is that it’s possible she could have recognized her killer. That is the thought that has crossed my mind. And I just want to ask that person why on earth did you do that to an old lady?”

Haberland Cray says she takes a lesson about handling her mother’s murder from what her mother taught her. “We were raised that when tragedy happens, you have two choices,” she says. “You can keep going forward putting one foot in front of the other, or you can sit in a corner and cry. We weren’t raised to do the later.”

One cold case in Alexandria led to the indictment of a suspect in a series of two other more recent murders that had the city locked down in the fears that there was a serial killer on

the loose.

On December 5, 2003, Nancy Dunning, wife of Alexandria Sheriff Jim Dunning, was shot and killed in her home. Ten years later, Ronald Kirby, transportation director for the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments, was also shot and killed in his home on November 11. Just a few months later, on February 6, 2014, Ruthanne Lodato was killed in her home, shot as she answered a knock on the door in the same manner as the Dunning and Kirby murders. Investigators believe that all three murders occurred around 11 a.m.

Lodato’s caretaker was also wounded, survived and became an eye witness to identify the shooter. Ballistics reports from the bullets used in all three cases proved they all came from the same small-caliber gun.

As those facts developed, Charles Severance, an Ashburn resident who ran for mayor of Alexandria twice and Congress once, became a person of interest to the Alexandria police as a result of a citizen tip. He matched the description of the eye witness and the police sketch, and he had had some run-ins with police. He was arrested on gun charges stemming from a Loudoun County incident on May 5, 2014, then extradited to Alexandria where he was arraigned on that gun charge. On September 8, he was charged with all three murders.

“I am confident that the suspect, Charles Severance, is the suspect we have been looking for for almost 11 years,” Alexandria Police Chief Earl Cook said during a press conference on September 8.

In Arlington County, Cold Case Detective Rosa Ortiz works 22 active cases. One of the first cases she worked when she came into the cold case unit from the sex crimes unit is the case of Stanford “Sam” Swift III, murdered as he counted the day’s money in the back office of an Arlington Roy Roger’s restaurant on June 11, 1992, where he worked as the night shift manager.

Police discovered his body there, where he had been stabbed in the head, and money was missing from the restaurant. A witness saw the killer running from the restaurant with a bag, and get into a car with D.C. plates. Police released a sketch of the suspect, but have not been able to solve the crime.

As with many cold cases, aging family members struggling with the loss are also nearing the end of their lives without the resolution they need about what happened, and why.

In the Swift case, his 81-year-old mother, Marian, used to call Detective Ortiz frequently about the case, but now “feels bad for calling” Ortiz for any news, according to her son, Peter Swift, Sam’s younger brother, who had just talked to his brother the day of his murder.

The sad truth is that his mother may never get the resolution she is seeking. She is running out of time. “My mother’s health is bad now, and she is just holding on the way she is in the hope of getting closure,” he says.

Peter remembers when detectives had a sketch of the suspect—described as a medium-build black man between 5-feet-9 and 5-feet-11-inches, in his late 20s with a moustache and a goatee—and thought the case would be solved quickly.

But that wasn’t the description of the suspect that Detective Ortiz showed them when she met with the family in 2002. She indicated it was another suspect—a smaller Caucasian guy who lived in Virginia at the time of the murder—who was already incarcerated in Seminole County in Florida. Oddly, Peter had just moved to the Orlando area, just five miles from where that suspect was jailed, to take a job in the hospitality business as he worked through the bitterness about his brother’s murder. “So, at that point, we really thought we had him,” he says. “I even got kind of crazy and thought, wow, I wish I can go to that jail and meet this guy. I thought what would I do if I was face to face with him. All kinds of stuff goes through your mind, like maybe killing him yourself,” he says. “But then, you kind of corral your emotions and start thinking sensibly again.” That was the last the family ever heard of that guy as a suspect in his brother’s case, he says.

The two Swift brothers were very close, which makes the pain of his murder harder to live with. His brother Sam was two years older than he was, was his best friend growing up and his biggest fan when he played sports in high school. Peter says that Sam was not a violent person, wasn’t aggressive, didn’t have bad habits and would never have put up a fight.

He had been a victim before, robbed when he was working for Family Dollar store in Dallas. During that robbery, he was hit on the head by a gun near his car as he was going to make a bank deposit.

This time, this robbery was different. “This was a senseless murder,” Swift says. “I mean, his hands were tied up with his own tie. What more of a threat are you at that point? And there was no forced entry.”

He says police think the perpetrator was hiding in the back room of the restaurant. “I don’t believe so,” Swift says. “I believe that my brother knew him. Those are my own thoughts on why this would have happened.”

Shortly after his brother’s murder, Swift left his job at Ralston Purina because, he says, “I couldn’t take the emotional drain. I couldn’t take the emotional bombardment of just hating people after that happened.”

His mother has never taken down pictures of Sam, and still has all of his stuff boxed up in a closet. “It’s her baby,” he says. “How do you ever get over losing a child?”

Ortiz says that, in cold cases like this, there is always the prospect that people will change and the case could get solved. “You committed this crime at a certain age, where there was a lot going on with you at the time,” she speculates. “Today, maybe you are a changed individual, and so things are different. I am going out and shaking trees to find you. But it’s always better if you come in and be accountable for your actions. Because any justice, even if it’s late, is still justice,” she says.

Another cold case in Arlington is the murder of 24-year-old Paul Matthew Zeller, an Iraq war veteran murdered on June 30, 2006, while walking near the Pentagon Row shopping center. Zeller, on his way home from working at a Honda dealership in College Park, Maryland, exited the Pentagon City metro station just before midnight and stopped at a nearby Harris Teeter grocery store. As he walked toward his home in the Aurora Highlands neighborhood in the 1300 block of South Joyce Street, someone shot him in the head with a shotgun.

The sound of that blast should have alerted hundreds of residents living in nearby high rises, but police have not discovered any witnesses to the murder.

Paul, an adopted child and the youngest of six children in the family, came from a long line of military people. His father, Dwight Zeller, is a retired Navy chaplain and the founder of a seminary in Westcliffe, in rural Colorado. “Paul finished high school and went into the 82nd Airborne and was with the group that went into Iraq from Kuwait,” Dwight Zeller says. “And he saw a lot of things that upset him a lot, which is natural. He was very disturbed.”

When he got back to Arlington and out of the Army in September 2004, he lived with his sister, Lydia Robertson, a Navy captain and retired public affairs officer for the U. S. Pacific Command, and her husband, an Army colonel. He got the job at the Honda dealership and appeared to be getting better, his father says. Then, for some reason, he was targeted for murder.

“Robbery didn’t seem to be part of the murder, and that is what makes it a mystery,” his father says. “It appears, and I use the word advisedly, that this could have been a random shooting of some kind. That is the only thing that the detectives have come up with.”

It would have been much easier to accept the murder of his child if he had been shot and killed in Iraq, Zeller says. “But it wasn’t. So that’s the way it is.”

He says he is not looking for peace or resolution, and doesn’t want to meet the perpetrator when that person is arrested, for a one-on-one talk about his son—except to ask that person why he did this. “Whoever did this, that just needs to be found out to serve the cause of justice,” he says.

The problem with cold cases is one of information—where did it come from, whether it can be believed, and what important resources and manhours will need to be spent on following up on the information. And then there is the problem of detectives revealing too much information publicly in an attempt to get the public involved in bringing in new information.

In fact, detectives who spoke about cold cases for this article varied broadly in discussing the details of what they knew about a case, and what they wanted the public to know about their investigations.

In Fairfax County, for example, there is no cold case unit listing cases on their website, and nobody from the cold case unit in Fairfax would comment on any investigations currently underway. “There are numerous investigative reasons why we would prefer not to release certain information that may jeopardize an investigation,” wrote Lieutenant Joshua Laitinen, spokesperson for the cold case and computer forensics unit at the Fairfax County police department.

Then there are people out there who will use any publicly released information to claim that they did it just to get attention. “That is one of the reasons that today, we are much more careful about what we release,” Prince William Detective Coady says. “We kind of hold some things back until we can be sure about it.”

The best thing the public can do, Coady says, is call the tip line. “Even if they have heard something, even if it was minor,” he says. “Sometimes the smallest nugget can break a case wide open.”

Can these cold case detectives ever count on what might be considered the good in people helping them? The jury is still out on that. “You were out there, you know you did it,” Loudoun County Detective Schochet says. “Are you going to die knowing that you killed somebody? Or were you a witness to that murder and you are not going to come forward and help some family get closure? Shame on you. I don’t know how you live with it.”

(December 2014)

Trending in NoVA

Subscribe & Save

From restaurants and shopping, to local events and activities, our monthly magazine is a must-read for anyone living or working in NoVA.

Subscribe