Making it easier for chefs to go whole hog

With breeds like Ossabaw, Mulefoot and Large Black, Spring House Farm’s pigs are the makings of farm-to-table fables. But trucking the immense black pigs from the farm in Lovettsville to the butcher to the chefs—most of whom wanted chops, not noses or tails—became a money-losing endeavor a few years in, says farmer Andrew Crush.

Despite all the nose-to-tail talk, Crush, who’s been raising animals since 2004, says he found many restaurant kitchens either didn’t want whole animals or lacked the space and training to break them down in-house.

“Restaurants were just cherry picking, and we were spending three days a week chasing our tails up and down the highway,” says Crush, who also raises chickens, goats, cows and rabbits. “We decided to draw a line in the sand.”

Three years ago, Crush went whole hog, informing his chef customers they’d need to buy more than pork chops to keep his pigs on their menus. (The farm’s CSA customers can buy individual cuts.)

When he’d nearly given up on selling to restaurants, he met Marc Pauvert.

A French master butcher working at the Four Seasons Hotel Baltimore, Pauvert stood out against a milieu of chefs whose menus were nose-to-tail in name only. He could butcher a hog in under 25 minutes, a task that takes skilled chefs hours, and turn its disparate pieces into dishes worthy of any menu.

Crush saw in Pauvert the opportunity to keep selling whole animals to chefs—with a side of butchering know-how. He hired him part-time to lead demonstrations at the farm and to work as a liaison with chefs wanting to sharpen their butchering skills or pick up a new recipe for rillettes.

“I can break down an animal, but Marc’s been doing it for 45 years,” says Justin Garrison, executive chef at the new West End Wine Bar & Pub in Purcellville, a customer of Crush’s and pupil of Pauvert’s. “It’s an added value with the farm, having a master butcher like Marc who can come in to help.”

Garrison worked with Spring House Farm’s meats most recently as executive chef at The Wine Kitchen in Leesburg, where a small space made it difficult to buy and store whole animals. With more room at West End, which opened last month, he can use the whole pig (and rabbits, too) across his menu—and he looks forward to Pauvert’s lessons. “As a chef, you can make more money if you know exactly what to do with the whole animal,” Garrison says.

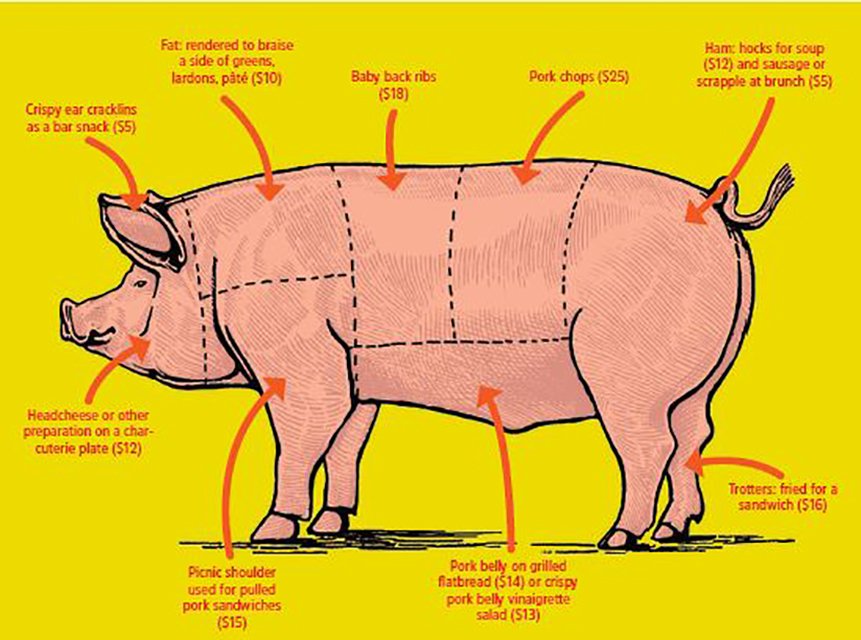

Scrapple, lardons, cracklings and headcheese are each made from under-appreciated portions of the pig and can star on brunch or bar menus. And when chefs pay $800 or $900 for the whole animal, it behooves them to find a purpose for every sinew.

The same is true for chefs sourcing just a few cuts of the costlier pigs and valuing them for their flavor. Copperwood Tavern in Shirlington has worked with Crush’s animals and Pauvert in the past, and several DC restaurants still do. A chef from Trummer’s On Main in Clifton cooked with Crush’s animals before taking the product to Baltimore’s Four Seasons (and introducing Crush and Pauvert).

Crush says “if they play their cards right,” restaurants can turn his pigs into dishes worth about five times the price of the animal. During a demonstration at the farm, Pauvert cut ribs close to the bone leaving more of the high-priced pork belly in tact, a trick he teaches chefs. Once restaurants commit to sourcing a whole pig from Crush, Pauvert meets with them to make every cut count for their menu.

His shrewd butchering helped cut the Four Seasons’ food costs by three percent after he came on board. And Crush is hopeful he can help other chefs do the same while sourcing higher on the hog. With public interest in grass-fed and local meats still growing, Crush plans to open a USDA-certified slaughterhouse facility and butcher shop that can turn whole animals into more customer-ready cuts later this year.

( February 2016 )