Constance Casserly’s “The House of Comprehension,” a practical guide to teaching literature, features graphics of a big bad wolf who menaces little pigs as they labor to build a sturdy shelter. The playful illustrations enliven the book’s stated objective—to empower students in secondary grades to build a “house of comprehension,” Casserly’s metaphor for the durable skill-set possessed by strong readers and writers.

The wolf, she says, might be the ubiquitous standardized test, or a school system obsessed with data collection, or a principal who micromanages teachers—in short, any of the forces currently bedeviling America’s educational climate, threatening to blow creativity and critical thinking skills, not to mention love of learning, to smithereens.

A 25-year veteran of Fairfax County Public Schools (FCPS) who retired in 2011, Casserly frequently devotes her weekly teaching blog to the various ripple effects of the testing frenzy that has evolved in recent years, ever since phrases like No Child Left Behind and Adequate Yearly Progress found their way into the educational lexicon. She is especially concerned about the dwindling morale of good teachers and fears they will slam the door on a profession that desperately needs them. Casserly herself resigned two years before she would have become eligible for full retirement benefits because she was fed up, a decision that she says had “nothing to do with kids or the classroom and everything to do with bureaucracy.”

Her early retreat echoes that of Ron Maggiano, an award-winning social studies teacher at West Springfield High School who lambasted Fairfax County’s new normal in a letter published last spring by the Washington Post. The piece went viral on social media, drawing attention to teachers’ growing frustrations. Like Casserly, Maggiano terminated his career while just shy of qualifying for full retirement funds because he could no longer support a system he believed was sacrificing its soul to Virginia’s Standards of Learning (SOL) tests.

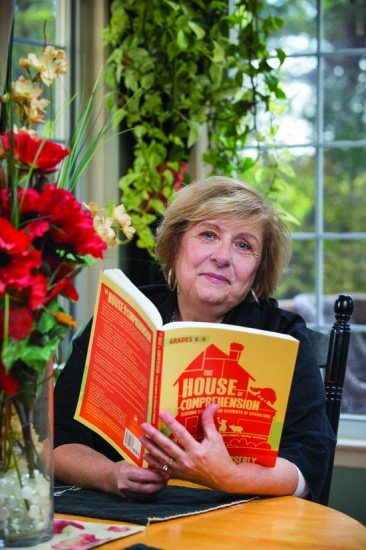

For Casserly, 65, closing the door to the schoolhouse did not mean she was through with teaching. The passion that kept her in the classroom for more than a quarter-century clearly lives on in her lively reminiscences, in the fervent flow of her convictions, and in the work she does to ward off the wolves.

The Teacher She Would Become

A spirited blonde whose energy belies her age, Casserly devotes many of her non-working hours to chasing her granddaughters and rooting for the Pittsburgh Steelers. Regular walks through her Herndon neighborhood help rev up ideas for her new career of instructional inspiration.

She was born and raised in the town of Indiana, Pa., the youngest of three girls. Her dad was a regional manager for Walgreens while her mom stayed home with the kids. After eight years of semi-private education, Casserly attended the town’s public high school, where a no-nonsense English teacher named Gertrude Handler would leave a lasting impression. She still marvels at the comments the teacher would write on her essays. The most memorable was, “Why do you hate the English language that you torture it so?” The eye-catching derogation challenged her to do better, she recalls, laughing when she considers the uproar that such a comment would spark in today’s schools, where humor or edginess on the part of the teacher is not always appreciated.

She went on to attend Indiana University of Pennsylvania, just blocks from where she grew up, majoring in English and earning her teaching certificate from a program that was known for graduating excellent teachers. Casserly recalls that her sensibilities as a small-town 21 year-old would soon be tested by her first teaching job. After getting married and moving to the Metro-D.C. area with her husband Tim, who was stationed at Fort Belvoir as a First Lieutenant in the Army, Casserly answered an ad for a reading teacher at the Boys’ Village of Maryland in Prince George’s County (now The Cheltenham Youth Facility). Even as she pulled up to the building, located on an elegant antebellum plantation and surrounded by a chain-link fence, she had no idea that this was a detention center for serious youth offenders.

Looking back, Casserly reflects, “The time I spent [at Boys’ Village] made me the teacher that I became.” She explains how eye opening it was to look at life through the eyes of those who had been reared in disadvantaged urban cultures—teenage boys who were already fathers and could not understand why, at her age, Casserly was not yet a mother. She recalls that they would often ask questions like, “’Can’t you have kids? Don’t you like kids?’”

Ultimately, the young teacher would transcend cultural barriers to forge the kind of break-through achievements reminiscent of Hilary Swank’s character in the movie “Freedom Writers.” Casserly developed a drama program based on the book “The Me Nobody Knows,” which compelled her students to push past both academic and emotional limits. One boy, a convicted armed robber who struggled to read, painstakingly learned his lines, projecting the agony of his experience into the part. The program earned recognition in the United States Congressional Record for its positive motivational impact.

Casserly would learn more about tolerance and reaching out—proclivities that she identifies as crucial to teaching in any environment—in subsequent jobs. After devoting 11 years to raising her two children, Kimberly and Matt, as an at-home mom, she took on two more teaching positions with challenged youth. One was at Graydon Manor, a facility in Leesburg for emotionally disturbed children and adolescents. The other was at the Enterprise School, a Fairfax County alternative school in Vienna, Casserly’s entry point into FCPS.

In 1985 Casserly moved to Herndon Middle School, where she taught English and creative writing. She encouraged her students to publish a pamphlet, “How to Survive Intermediate School” and a poetry booklet, “Split Personalities”.

During the 19 years she spent at Herndon High School, starting in 1992, Casserly continued juggling a variety of duties. Besides core classes, she taught journalism and creative writing, publishing the school’s award-winning literary magazine. To make good on her standing promise to students that she would always return their papers by the class period after they were turned in—within two days—she worked through lunch, at home and sometimes conquered paper stacks while her journalism kids cranked out the newspaper.

Composing Fine Lines

Casserly devoted her summers to doing what she loved second best, writing fiction. Over the years she wrote five novels. In 1992 she published “A Fine Line”, a young adult novel about a teenage girl with an abusive boyfriend. She was moved to write the book after a female student came to class with bruises. When Casserly inquired about them, the girl confessed that her boyfriend had struck her. Casserly was stunned when the girl added, “But it was my fault.”

This and other encounters with dating abuse among students resonated with the teacher in part because of her own experiences with a frighteningly controlling boyfriend. Just before her senior year in high school, she broke up with the young man, who then stalked her for years. He went so far as to assault another man with whom she had gone out on a date.

“A Fine Line” is set in a familiar locale, the halls of Herndon High School. The abusive boy lives in Great Falls. The author wanted to convey the often startling fact that dating abuse crosses all socio-economic levels.

Building a House

While finding a publisher for her other novels remains on Casserly’s to-do list, these days she immerses herself in writing and marketing curriculum materials, including the rich collection featured in “The House of Comprehension”, published last March. She also hammers away at her blog. She is clearly spurred by the desire to help rescue language arts instruction from the clutches of rote learning and hollow memorization—what she and other teachers decry as the byproducts of high-stakes standardized tests.

A few years ago she began posting lesson plans on TeacherspayTeachers.com and similar sites that allow educators to invest their resources in classroom-tested materials developed by practitioners like themselves—an alternative to the dull handouts typically featured in textbook ancillaries.

A quick flip through “The House of Comprehension” reveals that Casserly is no iconoclast, however. Rather than insurrection, she campaigns for balance and above all, an embrace of methods that evoke deep reading and thoughtful analysis. The book’s introductory chapter features a list of the Common Core State Standards (now adopted by 45 of the 50 states, with Virginia being one of the last hold-outs). Each of the book’s more than 40 classroom activity plans is aligned to three or four of the standards, which are identified at the top of that lesson’s teacher’s guide. Also identified are cognitive reasoning skills within the hierarchy of Bloom’s Taxonomy—with all-important verbs like “understand,” “support,” “synthesize” and “evaluate”—a framework that Casserly learned back in her days at IUP.

Adhering to the Common Core—or any other standards, says Casserly—should not mean that teachers forfeit opportunities to foster creativity and a sense of students’ ownership. “Let kids own it” is one of her mantras about effective teaching. And ownership evolves best, she believes, in settings where students work both individually and collaboratively, where they can make choices and have fun. “Teachers need to lead,” she says, “but they shouldn’t be drama queens who stand in front of the class and lecture the whole period.”

Premised on the idea that good readers “own” a strong understanding of the elements of literature (plot, character, tone and all those other things comprising the “house of comprehension”), the book invites students to closely examine each element in activities designated for before, during and after they read a work of literature. (And while the cover identifies grades 6-9 as the book’s target age group, Casserly agrees with the reviewer who endorses it for all secondary grades.) An activity titled “Time for Body Building” instructs students to “flesh out” characters in a story by examining them through various lenses. In “Let’s Tone Up,” they learn and apply attitude descriptors (words like “sneering,” “nostalgic” and “satirical”) and must support their claims with textual evidence (while teens are notorious for having plenty of “attitude,” they often lack the tools to convey someone else’s.) Elsewhere students construct charts with “visually pleasing elements” on symbols and theme. There’s also the “Literature Super Bowl,” complete with cut-out footballs and scoring sheets, for reviewing the literary elements at the end of a unit. Some of the activities culminate in writing assignments, including journal pieces and a classroom newspaper project.

When it comes to cultivating writers—perhaps the thorniest of all teaching tasks—Casserly challenges the status quo with her own hard-earned lessons. In one blog post, titled, “For the Love of Writing!” she points to a sad reality, one that would surely strike woe into the heart of any teacher: “More often than not, by the time students swing open the doors to middle school, their desire to express their thoughts on paper has been squashed.” She goes on to identify three of the causes: “compulsory insipid prompts, micromanaged writing formats and feelings of failure caused by minute line-by-line edits.”

To combat these menacing factors—call them big bad wolves—teachers must squash old habits, she says, inviting kids to take ownership and take heart in their writing. Assignments should always offer students ample choices, including a choose-your-own topic, whenever possible. The assignments should also be crafted with a creative or real-world angle: Students might have the option of arguing the character’s case as a defense lawyer, or reporting on an episode as a news commentator. Moreover, teachers should provide structure but steer clear of the ubiquitous and “stultifying” five-paragraph essay. Let students address their topic in three or thirteen or thirty paragraphs, if needed, she advises. When it comes to marking papers, she confesses that like the average English teacher armed with a soul-crushing colored pen, she was once guilty of drowning student papers in corrections. She finally came to her senses, she recalls, narrowing her focus to just three to four content and grammar areas per assignment.

Sparking the “Ah-ha!”

Casserly argues that effective teaching methods become their own reward by sparking “Ah-ha moments” in kids. She cites the boy in her class who astutely compared the band of characters in Ken Kesey’s “One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest” to Jesus and His Disciples. She recalls animated debates about the wisdom of John Proctor’s decision to climb the gallows in the final scene of “The Crucible”. And she still relishes the memory of back-and-forth ruminations about whether Gregor had indeed morphed into a giant dung beetle in Franz Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis”.

Casserly emphasizes that active learning methods provide a means to many ends—to breathtaking “Ah-ha” moments, and to the reasoning skills required by SOL tests. “When students can reach into their brains and pull out the necessary higher-level thinking skills they need to answer a question, they will pass the test,” she declares.

Restoring the Keys to the Kingdom

Teaching techniques aren’t everything, of course. The necessary complement to methodology is the set of attributes Casserly began cultivating way back in her days at the Boys’ Village: love, tolerance and flexible thinking. And since no educator is an island, a school system that supports the mission of teaching is crucial. Currently many school systems nationwide are suffering from structural deficiencies, she believes; call it the House of Apprehension. But like many of the soul-stirring literary works Casserly still adores, the current crisis foreshadows hope for redemption. She was encouraged by remarks made by FCPS school board members last July when they met to address growing concerns about what many see as a bureaucracy run amok. Superintendent Karen Garzy acknowledged that teachers were suffering from “initiative fatigue.” Garzy also talked about finding ways to empower teachers with greater autonomy over their classrooms. Hopefully, says Casserly, that goal will translate to a system that will “just let them teach!”

(November 2013)