He will go down in history as a foot soldier in one of America’s most noble and groundbreaking struggles, a man who suffered countless beatings and more than 40 arrests while refusing to wield a weapon or even raise a fist for a cause he deemed greater than himself. Yet Congressman John Lewis traces his earliest inspiration to creatures not commonly associated with heroism: chickens.

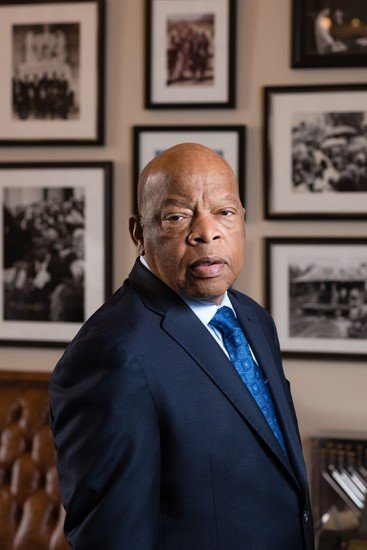

At his office in the historic Cannon Building on Capitol Hill, one finds a gallery of images from the civil rights era, featuring iconic figures like Martin Luther King Jr., John F. Kennedy, Bobby Kennedy—and, of course, John Lewis himself. One wall also displays a cartoon-like print of a boy surrounded by a flock of farmyard fowl. The whimsical depiction harks back to a childhood memory that Lewis is fond of recounting.

As a boy growing up in Troy, Alabama, the son of sharecroppers in the heart of the Jim Crow South, 5-year-old John Robert was tasked with caring for the family chickens. That meant feeding some five dozen birds and collecting their eggs on a daily basis. In his 1998 memoir, Walking with the Wind, he devotes several pages to the experience, calling it an “early glimpse into my future.” The henhouse became a kind of sanctuary where he would not only perform his chores but gaze lovingly at his charges, warm their eggs with his hands, talk to them, even preach the Gospel while they strutted and clucked—a primer of sorts for the seminary studies he would pursue as a young adult. Lewis explains his devotion by noting, “I now know the reason was their absolute innocence. They seemed so defenseless, so simple, so pure.” Their “outcast status” also drew him. Despite the common notion that they were “stupid, smelly nuisances,” Lewis perceived “a subtle grace and dignity in their every movement.”

Lifting the marginalized would indeed define his future. Now 76, the representative from Georgia has spent nearly all his life championing the cause of human dignity and equality.

He traces his journey from the restless stirrings of his boyhood to the spiritual and intellectual enlightenment of his early adult years, to episodes that left an indelible mark on American history: the sit-ins, the Freedom Rides and the many marches, including the march from Selma to Montgomery. As one of the “Big Six” leaders of the movement, Lewis stood at the forefront of these bold and perilous endeavors. He was only 23 when he delivered a passionate speech at the March on Washington, declaring that his people could no longer wait, could no longer be patient. As a congressman of nearly 30 years, he has devoted his career to actualizing King’s dream of a compassionate, inclusive society—what Lewis calls the Beloved Community. And as the last living speaker of that watershed event, he pays frequent tribute to his fallen corps and the transcendent forces that sustained their nonviolent resistance—mainly, their faith in what he calls the Spirit of History, that divine essence that compels humanity toward fulfillment of its better angels. Even today, the Spirit has its work cut out for itself, he insists.

In recent years, Lewis has embarked on a project aimed at bringing the movement into a new millennium: March, an autobiographical trilogy of graphic novels. One of his staffers, Andrew Aydin, came up with the idea after a casual conversation in which Lewis recalled the impact of a 10-cent comic book he read in the late ’50s—Martin Luther King Jr. and the Montgomery Story, a 16-page primer for young activists. Co-authored by Aydin and graphic artist Nate Powell, the first two books in the trilogy have earned accolades and a place on the New York Times best-seller list. (Book Three comes out in August.) In riveting words and pictures, the books provide the story of Lewis’ life and a window into a nation’s struggling soul. An early segment of Book One presents young Lewis preaching to his downtrodden chickens.

The books shed light on a man who has not only talked the talk but also marched the march.

A Humble Air

On the first floor of the Cannon Building, where lawmakers, aides and constituents come and go, Lewis greets visitors with a cordial handshake. He speaks with a pronounced Southern drawl and a humble air, the latter perhaps not what you’d expect from someone who played a key role in transforming a nation. Standing around 5 feet, 6 inches, his height likewise belies that historic stature. He sometimes jokes about being stouter and balder than he was five decades ago. True enough. At first glance, you might not recognize him as the slim young man who wore a trench coat and backpack as he led a crowd of hundreds across the Edmund Pettus bridge in Selma. But a close look reveals the same compelling eyes, the same strong jaw, the same aura of earnestness.

In one corner of his office, Lewis keeps a stack of photographs mounted on placards, epic scenes that he takes on school trips and other places where he’s invited to tell his story. Sometimes he displays one or two of them when delivering remarks on the House floor as visual aids to a powerful appeal.

Lewis grows animated as he combs through the images and relives some of the moments that defined his movement. In one, dating back to 1960, he and fellow activists are seated at a white-only lunch counter in downtown Nashville. “That was my first arrest,” he recalls matter-of-factly. “I bought that suit at a used clothing store for $5. I wanted to look sharp if I got arrested. ”

Elsewhere it is March 7, 1965, Bloody Sunday in Selma. Lewis, 25, is crouched down with his hands over his head as a policeman is raising his nightstick in a fury. Lewis would come away with a bloodied face and a fractured skull.

Listening to him raises questions: What ignites the kind of fire that spurs a person to rise up and demand change? How does one who is repeatedly brutalized resist the natural urge to fight back? And how does that person defeat the greatest enemy of all—despair?

Boyhood Stirrings

Lewis says from an early age, he was profoundly aware of black subjugation. In Troy, grown-ups told stories from “slavery times,” public facilities separated “white” from “colored,” and the Ku Klux Klan loomed as a threat to blacks who defied the norms.

Compelled to help his family of tenant farmers pick cotton in the scorching Alabama sun, Lewis resented not only the hard labor but also what it represented: “exploitation, hopelessness, a dead-end way of life.” Inequality likewise hit him hard for its impact on a precious commodity—his education. A passionate student with a thirst for knowledge, he longed to attend the pristine, columned school buildings that were the exclusive domain of white children. He also yearned to check out books from the public library.

At age 11 he took his first trip north, the first of several epiphany experiences. He and an uncle ventured 17 hours by car to Buffalo, a trek that required abundant food provisions and carefully orchestrated stops until they reached Ohio, where white-only signs would dissipate. Witnessing blacks mingling with whites in Northern cities came as a shock. Once back in Troy, he became “more acutely aware than ever” of the searing indignities his people suffered there.

Then came events connected to new winds sweeping the South. Lewis was 14 when the Supreme Court declared school segregation, that blatantly dishonest principle of “separate but equal,” unconstitutional. He recalls his elation: “No longer would I have to ride a broken-down bus almost 40 miles each day to attend classes at a ‘training’ school with hand-me-down books and supplies.” That assurance evaporated with reports of fierce pushback by Southern politicians who vowed defiance.

Less than a year later, in early 1955, Lewis would become mesmerized by a voice on the radio—that of a young black preacher who spoke in a soothing cadence. Unlike other ministers he had ever heard preach, this one expounded not the gates of heaven but “earthbound” issues, mainly the many doors that shut blacks out. He proffered hope through the “social gospel,” a doctrine of applying Christian principles to create a more just society. The voice was that of a man who would become Lewis’ mentor in the years ahead—the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Months later, Lewis was “shaken to the core” by news of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy brutally murdered in Mississippi after making a flirtatious remark to a white woman. Closer to home and similarly stunning was the fatal shooting of a distant relative who had been active in the NAACP. In both cases the white killer walked free.

By now Lewis had become riveted by a growing resistance. Fifty miles from Troy in Montgomery, a courageous soul named Rosa Parks had refused to surrender her bus seat to a white man, spearheading the first large-scale protest of the civil rights movement. Led by King, the Montgomery bus boycott lasted more than a year, during which Lewis scrutinized its course, marveling over the power of peaceful protest: “Those 50,000 black men and women in Montgomery were using their will and their dignity to take a stand … There was something about that kind of protest that felt very, very right.” Lewis would later say the boycott changed him more than any other single event of his life.

He would soon execute his own act of nonviolent protest, the first of many: writing a petition requesting that the local library open its doors to blacks. Though friends and classmates all shared his pain over segregation, only a few were willing to sign. The rest, responding to well-publicized atrocities inflicted on blacks who had contested the status quo, declined.

Though the library never responded to his petition, the experience emboldened Lewis with a sense that he could be proactive. It also exposed him to a peripheral adversary that lurked among blacks and bedeviled the cause of their liberation: fear of danger, even fear of change itself. Lewis’ parents spoke of King with “a mixture of awe and disapproval,” and they continually cautioned their son that “decent black folks stayed out of trouble.”

Venturing Trouble

But shortly after graduating high school, John Robert would indeed venture into trouble, what he now calls “good trouble, necessary trouble.” It’s something he frequently recommends to young people today as a means of combatting injustice.

In 1957 Lewis enrolled at the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, earning his stay by scrubbing pots in the dining hall. While he relished his studies in philosophy and religion and dreamed of taking his ministry from the henhouse to a real church, he was also restless to enlist in the battle for civil rights. After ABT’s president refused Lewis’ request to start a campus chapter of the NAACP, he resolved to affect change by applying to all-white Troy State University. Like the famed Little Rock Nine (led by Ernest Greene, whom he would later befriend), he would help eradicate racial barriers in the halls of education. When his application got no response, he wrote a letter to someone who would surely help—Dr. King himself.

After several correspondences, King, then 29, invited Lewis to meet with him and his team in Montgomery, an opportunity that was both daunting and exhilarating for “the boy from Troy,” as King would affectionately refer to him. They offered to help Lewis gain entry to the school but warned of the dangers. The first step would be to file a lawsuit against the state of Alabama. In the end, Lewis’ parents, fearful of losing their farm or worse, refused to grant their son permission. Nonetheless, the 18-year-old had now forged a connection to the lifeblood of the civil rights movement.

Back in Nashville, he would meet another trailblazer in Jim Lawson, a graduate student at Vanderbilt Divinity School, who was teaching workshops on nonviolent resistance at a local church. In Across That Bridge, Lewis’ 2012 memoir highlighting the intellectual and spiritual elements of this nonviolent crusade, he recalls that, “Our lessons taught the philosophy of Gandhi, Thoreau, Emerson, Plato, Aristotle, and others to illuminate the lineage of thinkers who believed in the inalienable rights of humankind.” Elsewhere he notes that long before it was a pop-culture slogan, he and fellow devotees were asking, “What would Jesus do?”

In their workshops they role-played to sharpen their skills in turning the other cheek when facing down slurs, fists, nightsticks, water hoses and worse. They learned to look attackers in the eye, to cover their heads, to refrain from cursing or hitting back. Lewis notes that the response was not passive but an act of will and an act of love. He emphasizes that they never hated anyone: “We were not struggling against people but against customs, traditions, a bad way of life.”

The first test of endurance took place at lunch counters in Nashville’s downtown stores, which permitted blacks to make purchases but banned them from dining or using fitting rooms. In their acts of civil disobedience, Lewis’ group adhered to planned procedures and a strict code of conduct, including rules for proper dress. Initially they would take their seats, request service and then quietly leave after it was denied. Gradually, their visits evolved into sit-ins. As the number of sit-ins grew and spread to other Southern cities, so did hostilities. Soon streets and jails were flooded with demonstrators, many of them bloodied from attacks. After prolonged negotiations with Nashville officials, the rebels triumphed. In May 1961, the first black patrons dined with dignity at Nashville’s stores.

On the heels of that success, Lewis ventured an even more provocative mission—the famed Freedom Rides. This time the goal was to defeat segregation on rails and buses across the South. As in the case of Brown v. Board of Education, Jim Crow had held its grip despite a high court ruling to desegregate. For several months, the riders boarded buses, occupying seats reserved for whites. They crisscrossed the South, including Virginia, encountering their ugliest challenges yet: police brutality, mob violence, even a firebombing. Lewis and several others endured three grueling weeks in a Mississippi penitentiary, where a guard ominously informed them, “Ain’t no newspapermen here.”

In the end, the movement scored another big win after the president ordered the National Guard to step in and enforce the law, earning Lewis and other founding riders what he calls “a measure of fame.” King presented Lewis with a $500 scholarship award, allowing him to broaden his studies at Nashville’s Fisk University.

But struggles persisted. In 1963 Alabama Gov. George Wallace famously proclaimed, “Segregation today, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!” Meanwhile, Lewis and other “Big Six” leaders were meeting with President Kennedy at the White House to plan the March on Washington, a historic high point that prompted conflicts of its own. On the eve of the March, Lewis was ordered to edit his speech, eliminating elements colleagues considered inflammatory—Communist-sounding words like “revolution” and statements sharply critical of the government.

Nearly two years and many demonstrations later, Lewis, now the National Chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, was organizing the grassroots in Selma. The focal point of their 54-mile march to Montgomery would be the new holy grail: voting rights. Throughout March 1965 he would encounter some of his greatest trials, including the horrors of Bloody Sunday. Ultimately, the beleaguered marchers, led by the young man in the trench coat and guarded by federal forces, succeeded in completing their historic five-day journey. “There was never a march like this one, and there hasn’t been one since,” Lewis reflects. That August, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, banning literacy tests and other barriers to voting and striking the biggest victory yet for the civil rights movement.

The congressman was deeply moved by Selma, the 2014 blockbuster movie featuring actor Stephan James in an uncannily accurate portrayal of Lewis. Recalling a filming session he had attended, Lewis told USA Today, “When I saw him on the set with my backpack and my trench coat, I wanted to say: ‘Boy, let me have my backpack. Let me have my trench coat. ’”

Even in dark moments—his brutal beating in Selma, King’s assassination in April 1968—Lewis never surrendered his faith. In an interview with Democracy Now, he reflected, “We had been tracked down by what I call the Spirit of History, and we couldn’t—we couldn’t turn back. We had to go forward. We became like trees planted by the rivers of water. We were anchored.”

Marching On

Lewis has never rested on his laurels. For 50 years and counting, he has continued championing rights of all stripes—women’s rights, gay rights, immigrant’s rights and more. When it comes to Black Lives Matter, he urges members to make their voices heard through disciplined, nonviolent protest. And when quite the opposite broke out at political rallies during the recent primary season, Lewis expressed dismay. When dismay turned to disgust, he posted a tweet to Donald Trump: “Have you no decency, Sir?”

Among his priorities (long before the current election season) is the restoration of voting rights, which he says have weakened in recent years after key provisions of the 1965 law were gutted. He argues that certain measures cropping up across the country, like voter ID laws and reductions in early voting days, constitute a deliberate effort to erode minority voting, a trend that shamefully maligns the cause that he and fellow activists risked their lives for.

Sitting across from Lewis in his office, surrounded by images of turmoil and triumph, one can only conclude that there are really no honors or medals that could possibly do him justice. None of the ones he has received over the years—the 50 or so honorary college degrees, the U.S. Navy’s announcement that it will name a ship after him, even the Presidential Medal of Freedom that Obama bestowed upon him in 2011, to name a few—seem sufficient.

Nor can anyone really capture John Lewis’ peculiar charm or humility. Those traits are probably summed up best by the story of a boy and his chickens.

(May 2016)