Prowling Shores, diving in swamps, Paleo Quest researchers’ expeditions for prehistoric treasure garner them the highest recognition.

By Tim Regan • Photography By Erick Gibson

As part of their citizen science effort Sharkfinder, Paleo Quest researchers Jason Osborne and Aaron Alford prowl the shores of the Chesapeake, dive deep into black swamp water and fill buckets with fossilized sea sediment to find ancient fossils. But they’re not doing it for fame or fortune, and they’re not doing it alone.

An outboard motor sputters as a boat cuts through waters. From the back of the vessel, Paleo Quest co-founder Jason Osborne divides his time between steering and scanning the chalky-white cliffs on shore. “There’s one,” he says nonchalantly. “There’s another one sticking out over there, could be a vertebrae.” From half a football field away, they’re spotting—and sometimes even identifying—fossilized material by color contrast alone. In the front seat of the small boat sits Aaron Alford, Osborne’s best friend and the other Paleo Quest co-founder.

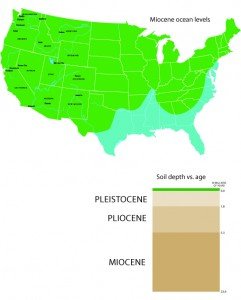

Today, they’re on an expedition off the shore of the Potomac River, between southern Maryland and eastern Virginia. This trip benefits Sharkfinder, a citizen science project supported by Paleo Quest. They’re searching for material deposited millions of years ago, when the Earth was warmer and the Atlantic Ocean stretched farther inland.

What may look like crumbling rocks piled up on the shoreline are actually mounds of ocean sediment. As underwater plants and marine creatures died, they fell to the sea floor. Over time, this organic material piled up and formed sediment layers—the closer to the surface a layer is, the more recently that material was deposited. It’s here, inside a cliff face made entirely of fossilized ocean bottom, that Alford and Osborne find proof that generation upon generation of massive sharks, ancient whales and huge fish once mingled and reproduced, ate and excreted, lived and died, as far back as 40 million years ago.

On shore, while Alford ties the boat to something sturdy, Osborne rushes to the crumbling wall to examine his findings. “Looks like someone got to this one first,” he says while dusting off a jagged, rocky object he says is part of a fossilized bone. “See here? Someone chipped this part off,” Osborne points at the chiseled remnants of what otherwise might have been a great find. That’s part of the game out here: getting to the good stuff before someone else—someone without the right tools or knowledge—does.

Because of this, some sites are so valuable to researchers that they’re not shared with the public. Though only accessible by boat, this is not one of those sites. When they’re lucky, the duo comes home with boatloads of teeth, whale vertebrae or in one case, an ultra-rare, fossilized bone from a seal skull.

When they’re not as lucky? Osborne yanks something out of the face of the wall like a loose tooth. “Fossilized fish turd,” he says, grinning mischievously. Luck or not, their end goal isn’t actually finding monster-sized fangs or the preserved jawbones of ancient mammals. That’s just the icing on the cake. They’re mainly here to collect raw data for science and education. Sharkfinder exists to do one thing: enlist a horde of students to pick through the material that the researchers don’t have time for. The students learn about fossils, and the researchers gain an army of crowd-sourced labor. And to do all that, Osborne and Alford must collect a lot of raw material—or matrix, as it’s called—for students to dig through.

Education for all

The afternoon sun beats down on Alford and Osborne. It’s been a mixed day—not much in the way of big fossils. They’re identifying layers of sediment and scooping huge handfuls into buckets —menial, but important work. This step is crucial to the Sharkfinder model. In order to provide the raw data the students need, the duo must dig into a specific layer, or “zone,” and fill a bucket with whatever’s there: dirt, rocks, hopefully fossils. Each zone bears its own significance to the time period which it relates.

From there, schools pay a fee for collection, a live presentation by Alford and Osborne, and to “license” the raw material. That’s where the students take over. “We’ll send about three and a half gallons of raw matrix. They sift through it and find everything that’s in it, they identify it, then send it back to a lab that we work with, and that lab publishes on it.” And those published papers credit students for those findings, which Alford says is an important part of the process. “We can’t just have them as slaves. We have to give them something. That’s an important part of our mission, to use [fossils] to get people’s attention, and sort of trick them into learning.”

Once the matrix has been picked through, Osborne and Alford travel to the school to deliver a capstone presentation that sometimes straddles the line between education and silliness. One of their favorite ways to break the ice? Pass around a piece of fossilized feces. “You don’t tell them what it is,” says Alford. “You tell these kids, you really want to engage this, so you want to taste it, smell it, and by the time it gets back to you, they’ve rubbed it over just about everything,” he says. Once they tell their audience what they’ve been examining, reactions range from extreme enthusiasm to complete and utter horror. But they’ve solved the most important part of the equation: they’ve convinced a sea of students to pay attention. “There’s some magic to those objects that just captures people,” says Alford. And based on student reactions and questions, Osborne says they’re actually learning, even pondering some pretty complex concepts.

Once, during a presentation in Houston, a sixth-grader asked how teeth evolved, an incredibly insightful question for a pre-adolescent student. “That’s the dream,” says Osborne. “Have some kid somewhere ask the questions that they desperately want to ask and give them the resources to do that using this platform.” All in all, Sharkfinder is a win-win: students get hands-on experience doing actual, real-world science, and researchers get more raw data than they could ever process alone. “We’ve created an environment where there’s discoveries for all, so let’s all get credit,” says Alford. And doing real, publishable work is exactly where students need to be nowadays.

Alford compares current STEM education to building a cardboard house in the classroom. Even if the house is accurate in every scalable way with all the working parts, he argues that students are still just building models of a house out of cardboard. And while it might be a decent model-building exercise, it doesn’t cut it at the end of the day if your goal is to inspire critical thinkers. “What we’ve been arguing is, why aren’t we doing real science? Science are those human activities that take place on the boundary of human knowledge.” Instead, it’s the hands-on research that Sharkfinder provides that really prepares students for a life of discovery. “If you’re going to train scientists, you have to throw them out into the unknown and say, you operate here. You need to be able to function here.”

Citizen scientists

The Paleo Quest founders are the first to admit they’re not professional paleontologists. In fact, this isn’t even their full-time jobs. Osborne builds laboratory tools for a living, and Alford, a health research scientist, has a Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins in psychiatric epidemiology. But both share a strong fascination for discovery—and fossils.

In a way, they’re professional amateurs—or “pro-ams,” as they affectionately call it. “We started Paleo Quest, basically, as a shelter to allow us to do that out of our day jobs,” says Alford. In the beginning, it was only the two of them, but as they spent their weekends digging up history, their newfound hobby became something more substantial. “We realized that we were finding things that were important to the local museums and everywhere else,” Alford says. So, they started submitting their recoveries, and as their skills grew, so did their team. Today, the Paleo Quest lineup includes a graphic designer, an editor, interns and researchers all working toward the same goal and sharing the same interests. “We have a handful of folks who bring their particular passion to the enterprise,” says Alford.

And that passion is paying off. Last June, Osborne accepted a Champion of Change award from The White House on behalf of the Sharkfinder program, an award given to only 12 other citizen science projects that year. Three years after co-founding Paleo Quest in 2010, Osborne stood on a stage at the White House and delivered an acceptance speech to a crowd of his most esteemed peers. “It was surreal,” says Osborne. And all of the winning projects had accepted millions of dollars in federal funding … except Sharkfinder, which operates without help from the federal government.

Despite the serious setting, Osborne took the opportunity to brag a little, a moment which Alford remembers fondly. “Jason was the last one to talk,” he says. “You could tell that there were tens of millions of dollars of federal funding involved [with the other winners] … Jason did some quick thinking and very cleverly mentioned the fact that we were the only self-funded program that got that award.” But they have a good reason to brag. Because of the way they crowdsource their research, Paleo Quest can help publish papers with Sharkfinder data that might cost a normal institution $100,000 to a $1 million dollars at a fraction of that amount.

“We’re getting out articles on less than a thousand dollars per article, so our return rate is phenomenally high,” says Alford. One of the reasons for their success is Osborne’s uncanny ability to charm people with money and influence. “Networking is Jason’s superpower,” says Alford. The other reason? The duo does what most scientists won’t to collect data.

Dirty work

Osborne and Alford have both had brushes with death. They can laugh about it now, but they recount their worst tales with just a hint of war story seriousness.

Once, when scuba diving for fossils in South Carolina’s Cooper River, Alford got a bad tank of air—that is, a scuba tank of oxygen that was tainted by carbon monoxide or another pollutant during bottling. While diving, he realized something was very wrong—his tank was emptying faster than normal because of the mishap. “I was so nauseous and so stupid from the poison,” explains Alford, who surfaced when it nearly ran out. “Because I had gone through my air so fast, I didn’t realize I was sick … but it really impacted my thinking.”

When he checked his gauge, he noticed he only had 300 pounds of air left, and in his oxygen-deprived state of mind, he figured Jason must be getting low, too. “I thought we were burning air at the same rate. We normally do.”

And when Osborne didn’t surface for another 20 minutes, Alford assumed he had run out of air underwater. “It was one of the blackest moments of my adult life. I thought my best friend was dead.” Although Osborne surfaced shortly thereafter loaded with goodies, Alford spent the rest of the day out of commission. “I’ve never had nausea like that.”

As if it couldn’t get worse, the very next day, while diving in the same black water, Alford watched helplessly as his diving partner came face-to-face with something out of a nightmare. “I’m trying to get my gear in the boat, and Jason starts screaming, ‘Cut him off! Get in the boat now! Bleep, bleep, bleep!’ and I’m like, who’s ‘him?’ So I rush to get my gear in, and I jam the throttle on the boat.”

And then Alford saw what the commotion was about—Osborne had walked into the path of an alligator that Alford says looked to be anywhere from five- to eight-feet long in the murky water. “They don’t show that on Nat Geo. I wouldn’t pay anybody to do that,” Osborne says.

Then there’s the time that Osborne got lost in an underwater cave on a different swamp dive and had to MacGyver his way out of it. “I didn’t know how to get out,” he says. “I had to follow my air bubbles to an exit.” The stories could go on forever, but dangerous as it might be, these risks are what Alford and Osborne’s services so in demand.

While normal paleontologists might lock themselves away in a dark laboratory most days of the year, the Paleo Quest researchers are in the field digging, diving and getting dirty. “Some of the spots, we’re diving under water and we’re taking samples back to the [United States Geological Survey] folks that we deal with … that’s really difficult, to get to those locations.”

And oftentimes they’re operating with a slightly lower regard for personal safety than most researchers in their field. “Imagine all the things your mom told you not to do,” says Alford. “We can do things that are high risk intellectually, high risk physically.” They come away with boatloads—literally—of raw data. “Our network of paleontologists … could continue to publish for the rest of their lives and still not have enough time to publish what we’ve given them,” Osborne says. “We talk to some of our science friends, and they say to us, ‘There’s no way in hell I would put myself out there like that because you’re really taking a risk.’ If you’re going to do really good science, it’s risky. And I think we’re doing really good science.”

(January 2014)