Long before 9/11, Peter Bergen was exploring the dark underworld of Islamist terror networks and the figure that stood at their center.

By Helen Mondloch / Photography by Erick Gibson

Long before 9/11, Peter Bergan was exploring the dark underworld of Islamist terror networks and the figure that stood at their center.

Long before 9/11, Peter Bergen was exploring the dark underworld of Islamist terror networks and the figure that stood at their center.

By Helen Mondloch / Photography by Erick Gibson

“My name is Peter, and I’d like to look around.”

That was the line uttered by CNN’s Peter Bergen when he showed up at Osama bin Laden’s compound in Pakistan to check out the scene of the deadly raid that had taken place there on May 1, 2011—or so the utterance was imagined by Daily Show host Jon Stewart.

In an on-air interview with Bergen, Stewart posed the line in mock speculation while marveling over the true fact that Bergen was the only journalist—the only outsider from anywhere, in fact—permitted access to the hideout of the world’s most infamous terrorist.

Bergen’s tour of the shattered compound in February 2012 wasn’t the first time the writer had ventured a close glimpse of the Al-Qaeda leader’s dark underworld. In 1997, Bergen and CNN colleague Peter Arnett journeyed to a mud hut in the mountains of Tora Bora in Afghanistan to conduct the first-ever televised interview with bin Laden. It was in that hour-long exchange that the bearded, soft-spoken sheik, an A-K 47 perched by his side, officially declared war on the United States.

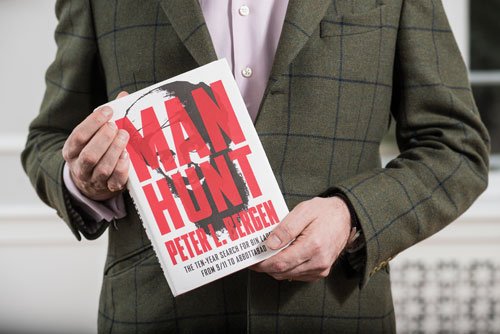

Bergen’s meeting with bin Laden would become a pivotal episode in a 30-year career of hands-on reporting largely focused on the Middle East. At 50, Bergen has produced award-winning documentaries for National Geographic and CNN, and his articles have appeared in more than two dozen publications, including The Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, Newsweek and Time. Since 9/11, he has authored four highly acclaimed books, including “Manhunt,” his latest tour de force about the 10-year search for bin Laden.

In addition to illuminating the terror front for general audiences, Bergen has spent the past decade composing specialized reports on a wide range of counterterrorism topics for those “serving in the weeds.”(Lately, he’s been analyzing the data on drone strikes.) The reports are published by the New America Foundation, the nonpartisan think tank where Bergen spends the bulk of his workdays as director of national security studies.

Early Forays

Bergen’s forays into the shadows of south Asia began in the early ‘80s, while the Minneapolis-born journalist, who was raised in London, was still studying at Oxford. He and a couple friends ventured a trip to Pakistan to chronicle the growing plight of Afghans who had fled the country in the wake of the Soviet invasion. The result was “Refuges of Faith,” a documentary that aired on British television.

After graduating with a master’s degree in modern history, Bergen moved to New York and worked various stints at ABC, including the job of desk assistant to Peter Jennings and production assistant to Barbara Walters. In 1990 he landed a job in the documentary unit at CNN, just in time to cover Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait and the subsequent outbreak of the first Gulf War.

Within a few years, Bergen would turn his gaze to a dark cloud emerging in the mountains of Afghanistan, where a little known jihadist group had begun training foot soldiers in the cause of holy war. Long before 9/11 awakened Americans to a brutal reality, Bergen would begin unveiling the complex, often surreal dimensions of Islamic terror networks and the figure that stood at their center. He would also deliver bold, sometimes shocking assessments of the U.S. government’s efforts at securing the homeland.

Pleasantly Matter-of-Fact

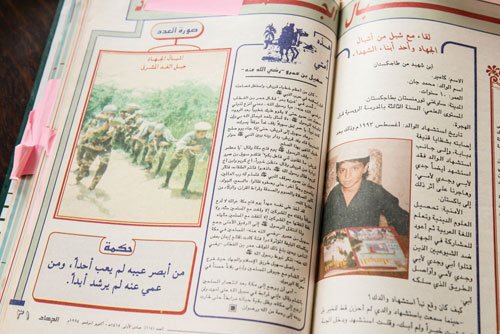

In the living room of his home in Northwest Washington, Peter Bergen is crumpling old editions of the Washington Post and feeding them into the fire. Like the seasoned wood floors and Palladian windows of this sparely decorated abode, his manner is unpretentious and inviting. On this Sunday afternoon in midwinter, the journalist is dressed in jeans and a wool sports coat, his wavy hair combed back in a manner that, like his staid British accent, underscores his professorial air. The bookshelves opposite the fireplace are teeming with treatises on history and public policy, biographies of Churchill and Hitler, even a stack of magazines on jihad that the author picked up in Afghanistan. One is not surprised to learn that he’s held teaching positions at Harvard and Johns Hopkins.

In the next room, 14-month-old Pierre crashes his toys and belts out an occasional scream, while Tresha Mabile, Bergen’s wife of five years (also a documentary producer and astute Mideast observer), clangs dishes and pans as she prepares a meal. Surround-sound opera adds to the pleasant cacophony.

With characteristic matter-of-factness, Bergen is expounding topics that are unimaginably weighty—the driving forces of terror, the state of the nation’s security, the government’s successes and failures since the events of 9/11. While he deliberates, Carolina the dog stands expectantly at his lap before passing out on the Oriental rug, no doubt wearied by the familiar gravitas of world affairs.

Against this breezy backdrop, Bergen himself punctuates the seriousness of his discourse with the levity evoked by his pleasant demeanor, and by an idiosyncrasy that was not lost on Jon Stewart: a high-pitched laugh that rises up in a startling burst. (Stewart called it a “very raucous laugh for a terrorism expert.”)

Considering the sober demands of his vocation, Bergen seems remarkably unjaded. In the 10 months that he spent writing “Manhunt,” he interviewed many senior officials at the White House, CIA, Department of Defense, State Department and other U.S. agencies—not to mention officials within the Pakistani military and intelligence complex.

In the midst of that endeavor, Tresha gave birth to their son. Bergen’s mother-in-law flew in to help, while the writer camped out in the basement, cranking out chapters about the most intensive “Manhunt” in history.

Tomorrow, says Bergen, he‘ll fly to Utah to attend a screening of the upcoming documentary version of “Manhunt” at the Sundance Film Festival. From there, he’ll take off for a regular visit to his haunts in the Middle East. None of which is cause for any excitement as he sips cappuccino by the fire, reflecting on his extraordinary encounters.

Path to a Terror Mastermind

In “Manhunt,” Bergen describes the Osama bin Laden whom he met in 1997 as “not the table-thumping revolutionary I had expected,” but rather as one who “presented himself as a low-key cleric.” He recalls that the words spoken by the leader were nonetheless “full of a raw hatred of the United States.” Bin Laden chillingly asserted that American civilians were “complicit” in U.S. foreign policy matters and, therefore, might not be spared from the imminent war.

Bergen described Osama bin Laden whom he met in 1997 as “not the table-thumping revolutionary I had expected.”

Asked what prompted an interest in bin Laden at a time when the terror mastermind was a little known figure to all but the most focused Mideast observers—even the bosses at CNN didn’t know bin Laden “from a hole in the wall”—Bergen indicates that the impetus evolved after the first World Trade Center bombing in 1993. When trial hearings revealed that the bombers, including mastermind Ramzi Yousef, had trained at jihadist camps in Afghanistan, Bergen alighted with the idea of launching a firsthand investigation. So he entreated his bosses to send him on a quest. Together with a team that included correspondent Peter Arnett, Bergen journeyed to the war-ravaged nation in 1993, gaining what was later hailed as astonishing access to the training camps and producing a documentary titled, “Terror Nation: US Creation?” The film made the thorny assertion that U.S. funding of Afghan militants during the 1980’s war with the Soviets helped engender America’s jihadist enemies. Moreover, the film astutely predicted that Afghanistan would become a lethal breeding ground for international terrorism in the years to come.

The following year, bin Laden’s name surfaced in a number of terrorism cases, including the trial of Ramzi Yousef. In 1996 the State Department released a fact sheet naming bin Laden—the son of a wealthy Saudi business mogul—the world’s most significant financier of Islamic terror. A provocative article about him soon appeared in the New York Times. All of which drove Bergen back to his bosses with a simple request: Send me and Arnett on another mission to the Afghan mountains, this time for a face-to-face meeting with bin Laden.

The venture was sure to be both risky and expensive. “Afghanistan was controlled by the Taliban, so it wasn’t like visiting Belgium,” remarks Bergen with his signature laugh.

Portrait of Radical Jihad

In his encounter with the mysterious sheik, Bergen concedes that he was unsure if bin Laden was earnest in his intents or a mere “blowhard.” The terror leader’s penchant for murdering innocents had not yet revealed itself. Unbeknownst to both Bergen and Arnett, the leader had already embarked, however, on contriving murderous attacks on American embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. In 1998, about a year after the interview, those facilities would be devastated in twin bombings that occurred just nine minutes apart. Bin Laden’s notoriety as a ruthless terrorist would become sealed by subsequent attacks, including the bombing of the USS Cole in 2000, which claimed the lives of 17 American service members.

By that time, Bergen was already sharpening his lenses on the al-Qaeda leader, probing the man behind the mystique by traversing the Middle East in search of bin Laden’s friends, acquaintances, former partners in jihad—anyone who could help him create a vivid and accurate portrait of the figure now threatening to afflict a painful wound on history.

The result was “Holy War, Inc: Inside the Secret World of bin Laden”—the first manuscript which was submitted to editors just weeks before 9/11, then quickly updated by a shell-shocked author for a November release. (In a C-SPAN interview that aired that year, the usually dispassionate Bergen recalled that on the morning of 9/11, he cried in the back seat of a cab, as did the driver, while news of the attacks was breaking.)

Far from the loosely structured gang of masked thugs that many Americans imagine, al-Qaeda in its heyday was a highly sophisticated enterprise

Five years and many inquiries later, Bergen would publish “The Osama bin Laden I Know: An Oral History of al-Qaeda’s Leader.” He would continue to probe the terrorist’s character from all angles even as he examined the complex dimensions of the war in Afghanistan in “The Longest War,” a richly compelling chronicle published in 2011.

That year Bergen expounded bin Laden’s religious zeal in an interview with NPR, saying, “Even as a kid, [bin Laden’s] idea of entertainment was to get a bunch of his buddies around and chant religious songs about the liberation of Palestine—not your typical teenager.”

Bin Laden’s devotion to a medieval reading of Islam is highlighted by the morbidly fascinating details of his adult life. Bergen explores the leader’s multiple marriages to women who, at the time of his death at age 54, ranged in age from 29 to 62. Three of his four wives, along with a dozen of his children and grandchildren, lived with him in Abbottabad, Pakistan, on a compound specially designed and built to serve as his lair. The living conditions, says Bergen, reflected bin Laden’s “ultra-fundamentalist” belief in austerity.

The author describes the compound’s main residence as one resembling a “makeshift but long-term campsite.” Despite frigid winters and sweltering summers, there was no air-conditioning and only a few portable heaters. There were no pictures or other décor—not even paint on the walls. The writer’s description of the terror leader’s toilet perhaps says it all: “I examined bin Laden’s tiny bathroom, about the size of a closet, and noticed that he used a toilet that was really only a hole in the floor over which he had to squat to do his business.”

Just as compelling as these glimpses of bin Laden’s Spartan existence is the portrait of the terror network he founded in 1989. Far from a loosely structured gang of masked thugs that many Americans imagine, al-Qaeda in its heyday was a highly sophisticated enterprise—one with a vast set of by-laws, including rules for employee conduct, pay scales, even policies for sick leave and vacation.

With the death of bin Laden and many of his top lieutenants (killed in recent years by U.S. drone strikes), Bergen has opined that the terror network is currently on “life support.” Strong evidence of its demise, he says, lies in the Arab Spring, a movement whose ideas are utterly antithetical to those of radical Islamism. “We do not, of course, know the final outcome of the Arab revolutions, but there is little chance that al-Qaeda or other extremist groups with be able to grab the reins of power as the authoritarian regimes of the Middle East crumble,” he notes.

Some of the most arresting passages of Bergen’s narratives explore the psychological dimensions of jihad—in bin Laden’s case, a blend of grievance, potent conspiracy theory and blinding religious fervor. (Bergen is emphatic that bin Laden hated the United States because of its foreign policy—and not, as President George Bush famously declared, because he despised American freedoms.)

Ten-Year “Manhunt”

At the heart of “Manhunt,” of course, is the riveting tale about how the most abominated criminal in recent history was tracked down and brought to justice. Much like the controversial movie “Zero Dark Thirty”—but with a firm commitment to accuracy—the book traces the path of CIA operatives who cracked the case by homing in on bin Laden’s now infamous courier. Bergen also profiles the moves of the fearsome NAVY Seals who descended on the compound in the middle of the night, and of the men and women poised in the White House Situation Room.

In the book and elsewhere, he has repeatedly characterized President Obama’s decision to carry out the raid as bold and exceptional. Referring with a hint of disdain to a comment made by Presidential candidate Mitt Romney, Bergen opines that the decision was definitely not one that “any president would have made.”

He adds, “Neither a President Biden nor a President Gates would have authorized the raid for fear, among other things, of pissing off the Pakistanis.” Bergen goes so far as to call Obama “the most aggressive [foreign policy] president in the modern era”—an assertion he hopes to illuminate in his next book.

Bold Assessments

Bergen’s remarks about U.S. maneuvers are sometimes less congratulatory. In “The Longest War” he notes: “There is sufficient truth to aspects of bin Laden’s criticism of American foreign policy for it to have real traction around the Muslim world.” (He also notes that the vast majority of Muslims around the world did not condone bin Laden’s use of terror.) He details “three obvious examples” of misplaced American policies: the unconditional support of Israel “at the expense of the Palestinian people”; the hypocrisy of “claiming to support democracy” while upholding repressive regimes like that of Saudi Arabia; and the invasion of Iraq.

Bergen has also exposed misdeeds on the part of the CIA, especially with regard to the practice of exiling detainees to countries where they are likely to be tortured (though he affirms the claims of Senator John McCain and others who insist that torture did not facilitate the finding of bin Laden).

On the home front, Bergen’s expertise on terror has informed a stark perspective on gun violence. In a CNN column published in the wake of the massacre in Newtown, Conn., he noted that jihadist terrorists killed 17 Americans in the U.S. since 9/11, whereas firearms exacted an astonishing toll of 88,000 Americans between 2003 and 2010 alone. In cities like New Orleans, he noted, residents are being shot and killed at a rate six times greater than that of Afghan civilians. He also delivered this: “… In the past decade, an American residing in the United States was around 5,000 times more likely to be killed by a fellow citizen armed with a gun than by a terrorist inspired by Osama bin Laden.”

On Stewart’s “The Daily Show,” Bergen casually demystified his exclusive tour of bin Laden’s hideout by citing the credibility he had earned with Pakistani authorities who served as the compound’s doorkeepers. Anyone choosing to follow Bergen’s journey into the shadows will come away similarly impressed and richly informed about the realms that still confound us.

(April 2013)